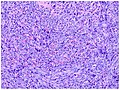

Castlemandisease (CD) describes a group of rare lymphoproliferative disorders that involve enlarged lymph nodes, and a broad range of inflammatory symptoms and laboratory abnormalities. Whether Castleman disease should be considered an autoimmune disease, cancer, or infectious disease is currently unknown.

AIDS-related lymphoma describes lymphomas occurring in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Rhadinovirus is a genus of viruses in the order Herpesvirales, in the family Herpesviridae, in the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae. Humans and other mammals serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated with this genus include: Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma and multicentric Castleman's disease, caused by Human gammaherpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). The term rhadino comes from the Latin fragile, referring to the tendency of the viral genome to break apart when it is isolated.

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the ninth known human herpesvirus; its formal name according to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) is Human gammaherpesvirus 8, or HHV-8 in short. Like other herpesviruses, its informal names are used interchangeably with its formal ICTV name. This virus causes Kaposi's sarcoma, a cancer commonly occurring in AIDS patients, as well as primary effusion lymphoma, HHV-8-associated multicentric Castleman's disease and KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome. It is one of seven currently known human cancer viruses, or oncoviruses. Even after many years since the discovery of KSHV/HHV8, there is no known cure for KSHV associated tumorigenesis.

An oncovirus or oncogenic virus is a virus that can cause cancer. This term originated from studies of acutely transforming retroviruses in the 1950–60s, when the term "oncornaviruses" was used to denote their RNA virus origin. With the letters "RNA" removed, it now refers to any virus with a DNA or RNA genome causing cancer and is synonymous with "tumor virus" or "cancer virus". The vast majority of human and animal viruses do not cause cancer, probably because of longstanding co-evolution between the virus and its host. Oncoviruses have been important not only in epidemiology, but also in investigations of cell cycle control mechanisms such as the retinoblastoma protein.

An opportunistic infection is an infection caused by pathogens that take advantage of an opportunity not normally available. These opportunities can stem from a variety of sources, such as a weakened immune system, an altered microbiome, or breached integumentary barriers. Many of these pathogens do not necessarily cause disease in a healthy host that has a non-compromised immune system, and can, in some cases, act as commensals until the balance of the immune system is disrupted. Opportunistic infections can also be attributed to pathogens which cause mild illness in healthy individuals but lead to more serious illness when given the opportunity to take advantage of an immunocompromised host.

AIDS-defining clinical conditions is the list of diseases published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that are associated with AIDS and used worldwide as a guideline for AIDS diagnosis. CDC exclusively uses the term AIDS-defining clinical conditions, but the other terms remain in common use.

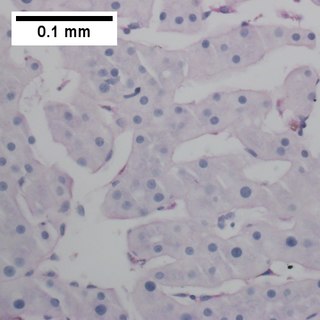

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is classified as a diffuse large B cell lymphoma. It is a rare malignancy of plasmablastic cells that occurs in individuals that are infected with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Plasmablasts are immature plasma cells, i.e. lymphocytes of the B-cell type that have differentiated into plasmablasts but because of their malignant nature do not differentiate into mature plasma cells but rather proliferate excessively and thereby cause life-threatening disease. In PEL, the proliferating plasmablastoid cells commonly accumulate within body cavities to produce effusions, primarily in the pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal cavities, without forming a contiguous tumor mass. In rare cases of these cavitary forms of PEL, the effusions develop in joints, the epidural space surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and underneath the capsule which forms around breast implants. Less frequently, individuals present with extracavitary primary effusion lymphomas, i.e., solid tumor masses not accompanied by effusions. The extracavitary tumors may develop in lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, the gastrointestinal tract, skin, spleen, liver, lungs, central nervous system, testes, paranasal sinuses, muscle, and, rarely, inside the vasculature and sinuses of lymph nodes. As their disease progresses, however, individuals with the classical effusion-form of PEL may develop extracavitary tumors and individuals with extracavitary PEL may develop cavitary effusions.

Robert Yarchoan is a medical researcher who played an important role in the development of the first effective drugs for AIDS. He is the Chief of the HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch in the NCI and also coordinates HIV/AIDS malignancy research throughout the NCI as director of the Office of HIV and AIDS Malignancy (OHAM).

Patrick S. Moore is an American virologist and epidemiologist who co-discovered together with his wife, Yuan Chang, two different human viruses causing the AIDS-related cancer Kaposi's sarcoma and the skin cancer Merkel cell carcinoma. Moore and Chang have discovered two of the seven known human viruses causing cancer. The couple met while in medical school together and were married in 1989 while they pursued fellowships at different universities.

Yuan Chang is a Taiwanese-born American virologist and pathologist who co-discovered together with her husband, Patrick S. Moore, the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and Merkel cell polyomavirus, two of the seven known human oncoviruses.

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is the common collective name for human betaherpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and human betaherpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B). These closely related viruses are two of the nine known herpesviruses that have humans as their primary host.

Merkel cell polyomavirus was first described in January 2008 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was the first example of a human viral pathogen discovered using unbiased metagenomic next-generation sequencing with a technique called digital transcriptome subtraction. MCV is one of seven currently known human oncoviruses. It is suspected to cause the majority of cases of Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare but aggressive form of skin cancer. Approximately 80% of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) tumors have been found to be infected with MCV. MCV appears to be a common—if not universal—infection of older children and adults. It is found in respiratory secretions, suggesting that it might be transmitted via a respiratory route. However, it has also been found elsewhere, such as in shedded healthy skin and gastrointestinal tract tissues, thus its precise mode of transmission remains unknown. In addition, recent studies suggest that this virus may latently infect the human sera and peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

The latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA-1) or latent nuclear antigen is a Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) latent protein initially found by Moore and colleagues as a speckled nuclear antigen present in primary effusion lymphoma cells that reacts with antibodies from patients with KS. It is the most immunodominant KSHV protein identified by Western-blotting as 222–234 kDa double bands migrate slower than the predicted molecular weight. LANA has been suspected of playing a crucial role in modulating viral and cellular gene expression. It is commonly used as an antigen in blood tests to detect antibodies in persons that have been exposed to KSHV.

Oral pigmentation is asymptomatic and does not usually cause any alteration to the texture or thickness of the affected area. The colour can be uniform or speckled and can appear solitary or as multiple lesions. Depending on the site, depth, and quantity of pigment, the appearance can vary considerably.

The stages of HIV infection are acute infection, latency, and AIDS. Acute infection lasts for several weeks and may include symptoms such as fever, swollen lymph nodes, inflammation of the throat, rash, muscle pain, malaise, and mouth and esophageal sores. The latency stage involves few or no symptoms and can last anywhere from two weeks to twenty years or more, depending on the individual. AIDS, the final stage of HIV infection, is defined by low CD4+ T cell counts, various opportunistic infections, cancers, and other conditions.

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a type of large B-cell lymphoma recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017 as belonging to a subgroup of lymphomas termed lymphoid neoplasms with plasmablastic differentiation. The other lymphoid neoplasms within this subgroup are: plasmablastic plasma cell lymphoma ; primary effusion lymphoma that is Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus positive or Kaposi's sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus negative; anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive large B-cell lymphoma; and human herpesvirus 8-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. All of these lymphomas are malignancies of plasmablasts, i.e. B-cells that have differentiated into plasmablasts but because of their malignant nature: fail to differentiate further into mature plasma cells; proliferate excessively; and accumulate in and injure various tissues and organs.

Large B-cell lymphoma arising in HHV8-associated multicentric Castleman's disease is a type of large B-cell lymphoma, recognized in the WHO 2008 classification. It is sometimes called the plasmablastic form of multicentric Castleman disease. It has sometimes been confused with plasmablastic lymphoma in the literature, although that is a dissimilar specific entity. It has variable CD20 expression and unmutated immunoglobulin variable region genes.

Human herpesvirus 8 associated multicentric Castleman disease is a subtype of Castleman disease, a group of rare lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by lymph node enlargement, characteristic features on microscopic analysis of enlarged lymph node tissue, and a range of symptoms and clinical findings.

Epstein–Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative diseases are a group of disorders in which one or more types of lymphoid cells, i.e. B cells, T cells, NK cells, and histiocytic-dendritic cells, are infected with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). This causes the infected cells to divide excessively, and is associated with the development of various non-cancerous, pre-cancerous, and cancerous lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). These LPDs include the well-known disorder occurring during the initial infection with the EBV, infectious mononucleosis, and the large number of subsequent disorders that may occur thereafter. The virus is usually involved in the development and/or progression of these LPDs although in some cases it may be an "innocent" bystander, i.e. present in, but not contributing to, the disease.