The United States National Security Council (NSC) is the principal forum used by the president of the United States for consideration of national security, military, and foreign policy matters. Based in the White House, it is part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, and composed of senior national security advisors and Cabinet officials.

Biodefense refers to measures to restore biosecurity to a group of organisms who are, or may be, subject to biological threats or infectious diseases. Biodefense is frequently discussed in the context of biowar or bioterrorism, and is generally considered a military or emergency response term.

The United States National Security council was established following the coordination of the foreign policy system in the United States in 1947 under the National Security Act of 1947. An administrative agency guiding national security issues was found to be needed since world war II. The national Security Act of 1947 provides the council with powers of setting up and adjusting foreign policies and reconcile diplomatic and military establishments. It established a Secretary of Defence, a National Military Establishment which serves as central intelligence agency and a National Security Resources Board. The specific structure of the United States National Security Council can be different depending on the elected party of the time. Different party emphasize on different aspects of policy making and administrating.

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military attack, national security is widely understood to include also non-military dimensions, such as the security from terrorism, minimization of crime, economic security, energy security, environmental security, food security, and cyber-security. Similarly, national security risks include, in addition to the actions of other nation states, action by violent non-state actors, by narcotic cartels, organized crime, by multinational corporations, and also the effects of natural disasters.

The Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) was a plan for space exploration announced on January 14, 2004 by President George W. Bush. It was conceived as a response to the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, the state of human spaceflight at NASA, and as a way to regain public enthusiasm for space exploration.

The U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century (USCNS/21), also known as the Hart-Rudman Commission or Hart-Rudman Task Force on Homeland Security, was chartered by Secretary of Defense William Cohen in 1998 to provide a comprehensive review of US national security requirements in the 21st century. USCNS/21 was tasked "to analyze the emerging international security environment; to develop a US national security strategy appropriate to that environment; and to assess the various security institutions for their current relevance to the effective and efficient implementation of that strategy, and to recommend adjustments as necessary".

Gregory L. Schulte was the U.S. ambassador to the International Atomic Energy Agency from July 2005 through June 2009. Schulte served as the Permanent Representative of the United States to the United Nations Office at Vienna, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and other international organizations in Vienna. Assuming his post on July 13, 2005, Schulte was charged with advancing the President's agenda in countering proliferation, terrorism, organized crime, and corruption, while promoting the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

The Directorate of Operations (DO), less formally called the Clandestine Service, is a component of the US Central Intelligence Agency. It was known as the Directorate of Plans from 1951 to 1973; as the Directorate of Operations from 1973 to 2005; and as the National Clandestine Service (NCS) from 2005 to 2015.

The United States under secretary of defense for policy (USDP) is a high level civilian official in the United States Department of Defense. The under secretary of defense for policy is the principal staff assistant and adviser to both the secretary of defense and the deputy secretary of defense for all matters concerning the formation of national security and defense policy.

Gilmore Commission is the informal and commonly used name for the U.S. Congressional Advisory Panel to Assess Domestic Response Capabilities for Terrorism Involving Weapons of Mass Destruction.

The Space Exploration Initiative was a 1989–1993 space public policy initiative of the George H. W. Bush administration.

The Legend-class cutter, also known as the National Security Cutter (NSC) and Maritime Security Cutter, Large, is the largest active patrol cutter class of the United States Coast Guard, with the size of a frigate. Entering into service in 2008, the Legend class is the largest of several new cutter designs developed as part of the Integrated Deepwater System Program.

Space policy is the political decision-making process for, and application of, public policy of a state regarding spaceflight and uses of outer space, both for civilian and military purposes. International treaties, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, attempt to maximize the peaceful uses of space and restrict the militarization of space.

Dual containment was an official US foreign policy aimed at containing Ba'athist Iraq and Revolutionary Iran. The term was first officially used in May 1993 by Martin Indyk at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and officially announced on February 24, 1994 at a symposium of the Middle East Policy Council by Indyk, who was the senior director for Middle East Affairs of the National Security Council (NSC).

Presidential Decision Directive 62 (PDD-62), titled Combating Terrorism, was a Presidential Decision Directive (PDD), signed on May 22, 1998 by President Bill Clinton. It identified the fight against terrorism a top national security priority.

The space policy of the Barack Obama administration was announced by U.S. President Barack Obama on April 15, 2010, at a major space policy speech at Kennedy Space Center. He committed to increasing NASA funding by $6 billion over five years and completing the design of a new heavy-lift launch vehicle by 2015 and to begin construction thereafter. He also predicted a U.S.-crewed orbital Mars mission by the mid-2030s, preceded by the Asteroid Redirect Mission by 2025. In response to concerns over job losses, Obama promised a $40 million effort to help Space Coast workers affected by the cancellation of the Space Shuttle program and Constellation program.

The space policy of the United States includes both the making of space policy through the legislative process, and the implementation of that policy in the United States' civilian and military space programs through regulatory agencies. The early history of United States space policy is linked to the US–Soviet Space Race of the 1960s, which gave way to the Space Shuttle program. At the moment, the US space policy is aimed at the exploration of the Moon and the subsequent colonization of Mars.

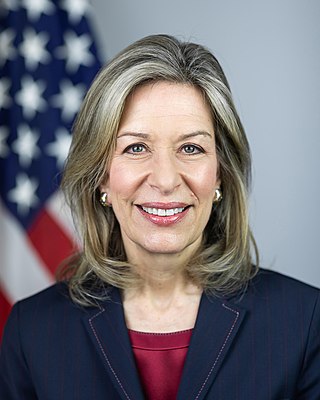

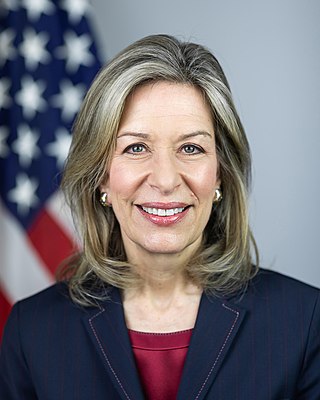

Elizabeth D. Sherwood-Randall is an American national security and energy leader, public servant, educator, and author currently serving as the 11th United States Homeland Security Advisor to President Joe Biden since 2021. She previously served in the Clinton and Obama Administrations and held appointments at academic institutions and think tanks.

In the United States, the National Biodefense Strategy is a biosecurity strategy that the federal government was directed to adopt by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017. The act—the periodic National Defense Authorization Act, the authorization bill for national security—required the secretaries of Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Agriculture to coordinate to produce a comprehensive strategy for countering biological warfare threats and other biological threats. The Donald Trump administration announced the National Biodefense Strategy of 2018 the following year. Later, the Donald Trump administration announced they would siphon funds from medical programs to supplement fundings for the strategy. When questioned about this, it was reported that the Obama administration provided the plans for the strategy.

Rear Admiral Kenneth Bernard is an American public health physician and expert on biodefense and health security policy. He served at the George W. Bush White House from 2002-2005 as Special Assistant to the President for Biodefense and as Assistant Surgeon General.