City Hotel

The hotel was constructed by Eleazer Early of Charleston, South Carolina, to a design by William Jay, [2] and completed in 1821 as the City Hotel. It was built on land purchased by his wife, Jane, four years earlier [2] and was the first hotel in Savannah. [1] It had "33 rooms, exclusive of the bar." [3] In January 1820, during the building's construction, it was damaged by the fire that swept through Savannah. It was at that point that Jane Early transferred the property into her husband's name. [2]

The hotel housed, as lessees, the first branch of the United States Post Office in the city, as well as a branch of the Second Bank of the United States, of which Eleazer Early was the first cashier. [2] [1] (William Jay is also responsible for the first branch of the bank in the city, [2] which was located on East St. Julian Street and built around the same time as the City Hotel. It was demolished in 1924.) [4] Jay's work can especially be seen in the building's interior, including marble mantels, fine woodwork, curved doors and doorways (like those he designed in the city's Richardson House), and a grand staircase "entrapped within the building's curved walls." [2]

In 1822, Early petitioned to have the elevated bridge built across Bay Lane to a building facing Bryan Street. [2] It is still there today. [5]

Early leased the hotel to Orran (possibly Oran) Byrd, also of Charleston, who agreed to a $4000 rental fee. [2] Byrd became the postmaster of the hotel's Post Office. [2] He placed a "classically bordered advertisement in Joshua Shaw's United States Directory for the Use of Travellers and Merchants [6] of 1823: [3]

This elegant establishment, which is entirely new with all its furniture and other arrangements, is in the centre of business and contiguous to the banks, and the post office is attached to the premises. All the stages start from the door.

In 1822, an ill-advised hotel venture on Tybee Island eventually led to Byrd falling behind on his rent to Early. As a result, in 1825, the Savannah sheriff advertised the sale of hotel furnishings. Although Byrd foundered, the hotel survived. [2]

Military dinners were held at the hotel, usually beginning at 4.00 p.m. to accommodate the numerous toasts that "numbered well over thirty." [2]

From 1826 until his death in August 1827, John Miller, of Augusta, was the hotel's manager. His wife succeeded him in the role. [2]

In December 1828, Captain Henry W. Lubbock, who had commanded the steamboat Macon, tried his hand at shore duty and became the hotel's manager. He undertook repairs and refurbishment. [2] As well as informing people that the hotel's stable could accommodate thirty horses, he also advertised that his bar was serving Vassar's Double Brown Ale on draught. [2] M. Vassar & Company was the largest brewery of its kind in the United States at the time. [7]

In May 1829, the hotel was sold, "at public outcry", in front of the Savannah Cotton Exchange. Eleazer Early had lost the property to the Bank of Darien. The bank, in turn, lost it to William J. Scott. Lubbock remained as manager, at least through the Fourth of July celebrations, [2] but he was succeeded in 1830 by Silas Hollis. [2] The following year, Hollis drummed up business by charging admission to view a lion and lioness on display in a large cage. [2] He also supplied the food and beverages for a hotel-sponsored dinner at the Cotton Exchange honoring John M. Berrien, attorney general of the United States. [2]

A fight between James Jones Stark and Dr. Philips Minis (a descendent of early Jewish settler Abraham Minis) [8] that began in the spring of 1832 in one Savannah bar (Luddington's) ended on August 10 in the bar of the City Hotel by virtue of Minis shooting Stark dead with a pistol. [2] Minis went on trial for the shooting.

Captain Peter Wiltberger Jr. (1791 – 1853) [9] purchased the property in December 1832 and renovated it. [2]

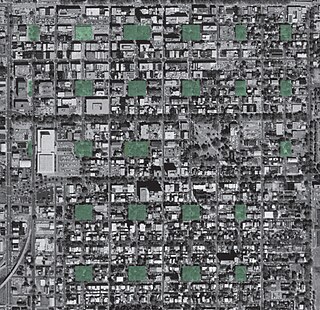

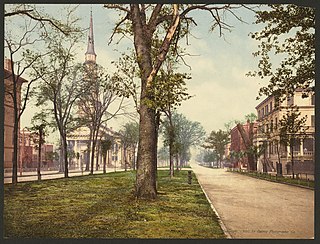

In the mid-1830s, the hotel's only real competition was from the Mansion House, a large double-piazzad wooden structure on the northwestern corner of Broughton and Whitaker Streets. [2] Wiltberger purchased that property in November 1836 for $10,000, as well as utilizing the northwest corner of Bull Street and Bryan Street, which he owned, and leasing tracts farther down Bryan, he began converting the property into a grand hotel he named the Pulaski House. [2] [10] [11]

Wiltberger decided to close the hotel on November 1, 1841, even though it was still operating successfully. [2]

The hotel was back in business within a month, under the proprietorship of Irishman John McMahon. [2] McMahon sold it to James B. Foley in the 1850s. Foley was acclaimed for managing to keep the establishment open through Savannah's yellow fever epidemic in 1854, the only public house in the city that did not close. [2] Some 650 Savannahians died in the epidemic. [12]

In 1857, a new hotel appeared on Johnson Square. On the southeast corner of Congress and Bull Streets, the Screven House replaced Wiltberger's Pulaski House "as Savannah's finest." [2] Foley was lured away from the City Hotel. [2]

The City Hotel struggled along in the final years before the Civil War, with Jackson Barnes and Edward Murphy as managers, before Augustus Bonaud (1822–1892) [13] took over what he called "a first-class hotel." [2] He charged $2 per day and $10 per week for board and lodging. In the first year of the war, the Union Army captured Hilton Head and the Union naval blockade restricted waterborne commerce. In April 1862, their capture of Fort Pulaski left Savannah in trouble. Bonaud managed to keep the hotel doors open until just before General Tecumseh Sherman reached Savannah in his March to the Sea in 1864. [2]

Hotel guests

In January 1822, General Winfield Scott stayed at the hotel, at a cost of $295 "for room, board, and a grand dinner." [2]

In 1825, naval commodores William Bainbridge, James Biddle and Lewis Warrenton were guests at a festive gathering, while the Marquis de Lafayette was also entertained there in March that year. Dinners were prepared at the hotel and delivered "down the block and across the street to the spacious ballroom [at the Cotton Exchange]." [2]

Retired British naval officer and scientist Captain Basil Hall and his wife of three years, Margaret, stayed at the hotel in 1828. [2]

John James Audubon stayed at the hotel in March 1832 after having to divert to the city when a gale forced into shore the schooner on which he was bound for Charleston. [2]

Later uses

In October 1865, the building was leased to "parties in Savannah", the portico was removed, and the two lower floors converted into two stores. [2]

Ownership from the 1860s bounced around several Savannah families, including the O'Byrnes, the Gilberts and the Osbornes. [2]

By the turn of the 20th century, the building was used as a lumber and coal warehouse, then for general storage. [1] In 1917 it was owned by John C. Coleman, of Effingham County. [2]

In 1951, Thomas W. Gamble, son of the mayor and historian Thomas Gamble, purchased the property for his Review Company. William H. Thompson and his Thompson Transfer Company moved out at the same time. Thompson, 77, had occupied his space for 44 years. [2]

In the 1960s, it became an office-supplies store, including a large printing press. [1] Hurricane David tore the roof of the building in 1979, forcing the business to close. [14]