| Printing press | |

|---|---|

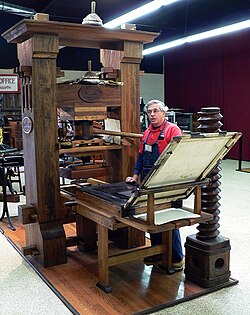

A recreated Gutenberg press at the International Printing Museum in Carson, California | |

| Classification | Machine |

| Application | Printing |

| Inventor | Johannes Gutenberg |

| Invented | 1440 |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of printing |

|---|

|

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the cloth, paper, or other medium was brushed or rubbed repeatedly to achieve the transfer of ink and accelerated the process. Typically used for texts, the invention and global spread of the printing press was one of the most influential events in the second millennium. [1] [2]

Contents

- History

- Economic conditions and intellectual climate

- Technological factors

- Function and approach

- Gutenberg's press

- The printing revolution

- Mass production and spread of printed books

- Circulation of information and ideas

- Industrial printing presses

- Rotary press

- Printing capacity

- Gallery

- See also

- Notes

- Bibliography

- External links

In Germany, around 1440, the goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable-type printing press, which started the Printing Revolution. Modelled on the design of existing screw presses, a single Renaissance movable-type printing press could produce up to 3,600 pages per workday, [3] compared to forty by hand-printing and a few by hand-copying. [4] Gutenberg's newly devised hand mould made possible the precise and rapid creation of metal movable type in large quantities. His two inventions, the hand mould and the movable-type printing press, together drastically reduced the cost of printing books and other documents in Europe, particularly for shorter print runs.

From Mainz, the movable-type printing press spread within several decades to over 200 cities in a dozen European countries. [5] By 1500, printing presses in operation throughout Western Europe had already produced more than 20 million volumes. [5] In the 16th century, with presses spreading further afield, their output rose tenfold to an estimated 150 to 200 million copies. [5] The earliest press in the Western Hemisphere was established by Spaniards in New Spain in 1539, [6] and by the mid-17th century, the first printing presses arrived in British colonial America in response to the increasing demand for Bibles and other religious literature. [7] The operation of a press became synonymous with the enterprise of printing and lent its name to a new medium of expression and communication, "the press". [8]

The spread of mechanical movable type printing in Europe in the Renaissance introduced the era of mass communication, which permanently altered the structure of society. The relatively unrestricted circulation of information and ideas transcended borders, captured the masses in the Reformation, linked the collaborative networks of the Scientific Revolution, and threatened the power of political and religious authorities. The sharp increase in literacy broke the monopoly of the literate elite on education and learning and bolstered the emerging middle class. Across Europe, the increasing cultural self-awareness of its peoples led to the rise of proto-nationalism and accelerated the development of European vernaculars, to the detriment of Latin's status as lingua franca. [9] In the 19th century, the replacement of the hand-operated Gutenberg-style press by steam-powered rotary presses allowed printing on an industrial scale. [10]