Thomas Robert Malthus was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

Economic history is the study of history using methodological tools from economics or with a special attention to economic phenomena. Research is conducted using a combination of historical methods, statistical methods and the application of economic theory to historical situations and institutions. The field can encompass a wide variety of topics, including equality, finance, technology, labour, and business. It emphasizes historicizing the economy itself, analyzing it as a dynamic entity and attempting to provide insights into the way it is structured and conceived.

The bourgeoisie is a class of business owners and merchants which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted with the proletariat by their wealth, political power, and education, as well as their access to and control of cultural, social and financial capital. They are sometimes divided into a petty, middle, large, upper, and ancient bourgeoisie and collectively designated as "the bourgeoisie".

Economic growth can be defined as the increase or improvement in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy in a financial year. Statisticians conventionally measure such growth as the percent rate of increase in the real and nominal gross domestic product (GDP).

Robert Merton Solow, GCIH is an American economist whose work on the theory of economic growth culminated in the exogenous growth model named after him. He is currently Emeritus Institute Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he has been a professor since 1949. He was awarded the John Bates Clark Medal in 1961, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1987, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014. Four of his PhD students, George Akerlof, Joseph Stiglitz, Peter Diamond and William Nordhaus later received Nobel Memorial Prizes in Economic Sciences in their own right.

The idea of convergence in economics is the hypothesis that poorer economies' per capita incomes will tend to grow at faster rates than richer economies. In the Solow-Swan growth model, economic growth is driven by the accumulation of physical capital until this optimum level of capital per worker, which is the "steady state" is reached, where output, consumption and capital are constant. The model predicts more rapid growth when the level of physical capital per capita is low, something often referred to as “catch up” growth. As a result, all economies should eventually converge in terms of per capita income. Developing countries have the potential to grow at a faster rate than developed countries because diminishing returns are not as strong as in capital-rich countries. Furthermore, poorer countries can replicate the production methods, technologies, and institutions of developed countries.

Malthusianism is the theory that population growth is potentially exponential, according to the Malthusian growth model, while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population decline. This event, called a Malthusian catastrophe occurs when population growth outpaces agricultural production, causing famine or war, resulting in poverty and depopulation. Such a catastrophe inevitably has the effect of forcing the population to "correct" back to a lower, more easily sustainable level. Malthusianism has been linked to a variety of political and social movements, but almost always refers to advocates of population control.

The Solow–Swan model or exogenous growth model is an economic model of long-run economic growth. It attempts to explain long-run economic growth by looking at capital accumulation, labor or population growth, and increases in productivity largely driven by technological progress. At its core, it is an aggregate production function, often specified to be of Cobb–Douglas type, which enables the model "to make contact with microeconomics". The model was developed independently by Robert Solow and Trevor Swan in 1956, and superseded the Keynesian Harrod–Domar model.

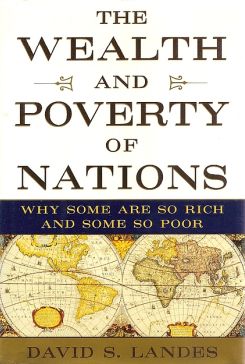

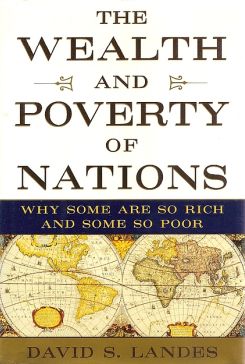

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some are So Rich and Some So Poor is a 1998 book by historian and economist David Landes (1924–2013). He attempted to explain why some countries and regions experienced near miraculous periods of explosive growth while the rest of the world stagnated. The book compared the long-term economic histories of different regions, specifically Europe, United States, Japan, China, the Arab world, and Latin America. In addition to analyzing economic and cliometric figures, he credited intangible assets, such as culture and enterprise, to explain economic success or failure.

Deirdre Nansen McCloskey is the distinguished professor of economics, history, English, and communication at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). She is also adjunct professor of philosophy and classics there, and for five years was a visiting professor of philosophy at Erasmus University, Rotterdam. Since October 2007 she has received six honorary doctorates. In 2013, she received the Julian L. Simon Memorial Award from the Competitive Enterprise Institute for her work examining factors in history that led to advancement in human achievement and prosperity. Her main research interests include the origins of the modern world, the misuse of statistical significance in economics and other sciences, and the study of capitalism, among many others.

The book An Essay on the Principle of Population was first published anonymously in 1798, but the author was soon identified as Thomas Robert Malthus. The book warned of future difficulties, on an interpretation of the population increasing in geometric progression while food production increased in an arithmetic progression, which would leave a difference resulting in the want of food and famine, unless birth rates decreased.

Ha-Joon Chang is a South Korean institutional economist, specialising in development economics. Chang is the author of several widely discussed policy books, most notably Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective (2002). In 2013, Prospect magazine ranked Chang as one of the top 20 World Thinkers.

Geography and wealth have long been perceived as correlated attributes of nations. Scholars such as Jeffrey D. Sachs argue that geography has a key role in the development of a nation's economic growth. For instance, nations that reside along coastal regions, or those who have access to a nearby water source, are more plentiful and able to trade with neighboring nations. In addition, countries that have a tropical climate face a significant amount of difficulties such as disease, intense weather patterns, and lower agricultural productivity. This thesis is supported by the fact that the volumes of UV radiation have a negative impact on economic activity. There are a number of studies confirming that spatial development in countries with higher levels of economic development differs from countries with lower levels of development. The correlation between geography and a nation's wealth can be observed by examining a country's GDP per capita, which takes into account a nation's economic output and population.

Joel Mokyr is a Netherlands-born American-Israeli economic historian. He is a professor of economics and history at Northwestern University, where he has taught since 1974; in 1994 he was named the Robert H. Strotz Professor of Arts and Sciences. He is also a Sackler Professorial Fellow at the University of Tel Aviv's Eitan Berglas School of Economics.

Gregory Clark is an economic historian at the University of Southern Denmark. He is known for his economic research on the industrial revolution and social mobility.

Plutonomy is the science of production and distribution of wealth.

Stephen T. Ziliak is an American professor of economics whose research and essays span disciplines from statistics and beer brewing to medicine and poetry. He is currently a faculty member of the Angiogenesis Foundation, conjoint professor of business and law at the University of Newcastle in Australia, and professor of economics at Roosevelt University in Chicago, IL. He previously taught for the Georgia Institute of Technology, Emory University, and Bowling Green State University. Much of his work has focused on welfare and poverty, rhetoric, public policy, and the history and philosophy of science and statistics. Most known for his works in the field of statistical significance, Ziliak gained notoriety from his 1996 article, "The Standard Error of Regressions", from a sequel study in 2004 called "Size Matters", and for his University of Michigan Press best-selling and critically acclaimed book The Cult of Statistical Significance: How the Standard Error Costs Us Jobs, Justice, and Lives (2008) all coauthored with Deirdre McCloskey.

The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All the Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better is a pamphlet by Tyler Cowen published in 2011. It argues that the American economy has reached a historical technological plateau and the factors that drove economic growth for most of America's history are no longer present. These figurative "low-hanging fruit" include the cultivation of much free, previously unused land, technological breakthroughs in transport, refrigeration, electricity, mass communications, sanitation, and the growth of education. Cowen, a professor of economics at George Mason University, theorizes that these factors have contributed to stagnation in the median American wage since 1973.

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World is a 2010 book by economist and social theorist Deirdre McCloskey that is the second of a three-book series laying out the thesis that a change in the rhetoric surrounding the value of business, innovation, and entrepreneurship was the main factor responsible for the takeoff of economic growth in Northwest Europe in the late 18th century. Bourgeois Dignity focuses on arguing that there was a fairly significant and unprecedented takeoff of economic growth, and that existing explanations for this takeoff are inadequate. McCloskey provides a rough outline for why she thinks that the changes in rhetoric surrounding the dignity of business and markets were crucial, but leaves the elaborate case for later books in the series.

The term middle-class values is used by various writers and politicians to include such qualities as hard work, self-discipline, thrift, honesty, aspiration and ambition. Thus, people in lower or upper classes can also possess middle-class values, they are not exclusive to people who are actually middle-class. Contemporary politicians in Western countries frequently refer to such values, and to the middle-class families that uphold them, as worthy of political support.