The 9th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1805, to March 4, 1807, during the fifth and sixth years of Thomas Jefferson's presidency. The apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives was based on the 1800 United States census. Both chambers had a Democratic-Republican majority.

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of reservations. The various Acts were also intended to regulate commerce between settlers and the natives. The most notable provisions of the Act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

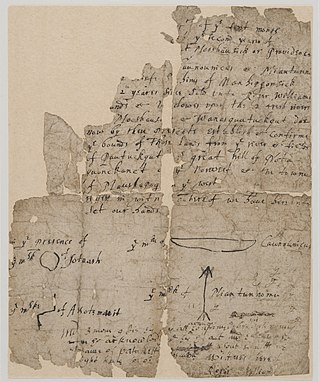

The Walking Purchase was a 1737 agreement between the Penn family, the original proprietors of the Province of Pennsylvania, later the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the Lenape native Indians. In the purchase, the Penn family and proprietors claimed that a 1686 treaty with the Lenape ceded an area of 1,200,000 acres (4,860 km2) in northeastern Pennsylvania, and forced them to vacate. The area is along the northern reaches of the Delaware River, on Pennsylvania's border with what was called, at the time, West New Jersey. Encyclopædia Britannica refers to the treaty as a "land swindle". The Lenape appealed to the Iroquois Indian tribe to their north for aid on the issue, but the Iroquois refused their request, ultimately siding with the Penn interests.

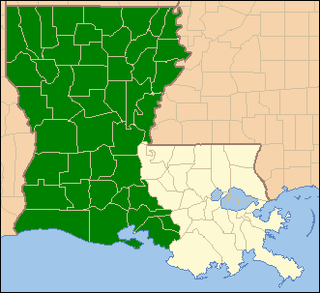

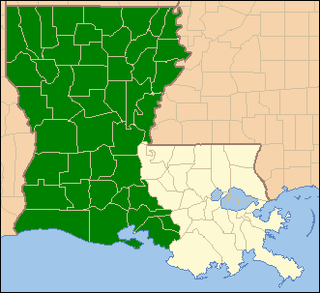

The United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana is a United States federal court with jurisdiction over approximately two thirds of the state of Louisiana, with courts in Alexandria, Lafayette, Lake Charles, Monroe, and Shreveport. These cities comprise the Western District of Louisiana.

Same-sex marriage in Louisiana has been legal since the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015. The court held that the denial of marriage rights to same-sex couples is unconstitutional, invalidating Louisiana's ban on same-sex marriage. The ruling clarified conflicting court rulings on whether state officials are obligated to license same-sex marriages. Governor Bobby Jindal confirmed on June 28 that Louisiana would comply with the ruling once the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed its decision in a Louisiana case, which the Fifth Circuit did on July 1. Jindal then said the state would not comply with the ruling until the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana reversed its judgment, which it did on July 2. All parishes now issue marriage licenses in accordance with federal law.

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida, 414 U.S. 661 (1974), is a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court concerning aboriginal title in the United States. The original suit in this matter was the first modern-day Native American land claim litigated in the federal court system rather than before the Indian Claims Commission. It was also the first to go to final judgement.

County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State, 470 U.S. 226 (1985), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case concerning aboriginal title in the United States. The case, sometimes referred to as Oneida II, was "the first Indian land claim case won on the basis of the Nonintercourse Act."

Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy, 162 U.S. 283 (1896), was the first litigation of aboriginal title in the United States by a tribal plaintiff in the Supreme Court of the United States since Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831). It was the first such litigation by an indigenous plaintiff since Fellows v. Blacksmith (1857) and its companion case of New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble (1858). The New York courts held that the 1788 Phelps and Gorham Purchase did not violate the Nonintercourse Act, one of the provisions of which prohibits purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government, and that the Seneca Nation of New York was barred by the state statute of limitations from challenging the transfer of title. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the merits of lower court ruling because of the adequate and independent state grounds doctrine.

Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, 528 F.2d 370, was a landmark decision regarding aboriginal title in the United States. The United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit held that the Nonintercourse Act applied to the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot, non-federally-recognized Indian tribes, and established a trust relationship between those tribes and the federal government that the State of Maine could not terminate.

The Marshall Court (1801–1835) issued some of the earliest and most influential opinions by the Supreme Court of the United States on the status of aboriginal title in the United States, several of them written by Chief Justice John Marshall himself. However, without exception, the remarks of the Court on aboriginal title during this period are dicta. Only one indigenous litigant ever appeared before the Marshall Court, and there, Marshall dismissed the case for lack of original jurisdiction.

Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 was a proclamation by the Congress of the Confederation dated September 22, 1783 prohibiting the extinguishment of aboriginal title in the United States without the consent of the federal government. The policy underlying the proclamation was inaugurated by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and continued after the ratification of the United States Constitution by the Nonintercourse Acts of 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1833.

The Narragansett land claim was one of the first litigations of aboriginal title in the United States in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida (1974), or Oneida I, decision. The Narragansett claimed a few thousand acres of land in and around Charlestown, Rhode Island, challenging a variety of early 19th century land transfers as violations of the Nonintercourse Act, suing both the state and private land owners.

Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki, 413 F.3d 266, is an important precedent in the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit for the litigation of aboriginal title in the United States. Applying the U.S. Supreme Court's recent ruling in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York (2005), a divided panel held that the equitable doctrine of laches bars all tribal land claims sounding in ejectment or trespass, for both tribal plaintiffs and the federal government as plaintiff-intervenor.

Aboriginal title in New York refers to treaties, purchases, laws and litigation associated with land titles of aboriginal peoples of New York, in particular, to dispossession of those lands by actions of European Americans. The European purchase of lands from indigenous populations dates back to the legendary Dutch purchase of Manhattan in 1626, "the most famous land transaction of all." More than any other state, New York disregarded the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 and the follow-on Nonintercourse Acts, purchasing the majority of the state directly from the Iroquois nations without federal involvement or ratification.

South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc., 476 U.S. 498 (1986), is an important U.S. Supreme Court precedent for aboriginal title in the United States decided in the wake of County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State (1985). Distinguishing Oneida II, the Court held that federal policy did not preclude the application of a state statute of limitations to the land claim of a tribe that had been terminated, such as the Catawba tribe.

Aboriginal title in California refers to the aboriginal title land rights of the indigenous peoples of California. The state is unique in that no Native American tribe in California is the counterparty to a ratified federal treaty. Therefore, all the Indian reservations in the state were created by federal statute or executive order.

Aboriginal land title in New Mexico is unique among aboriginal title in the United States. Congressional legislation was passed to define such title after the United States acquired this territory following war with Mexico (1846-1848). But the Supreme Court of the New Mexico Territory and the United States Supreme Court held that the Nonintercourse Act did not restrict the alienability of Pueblo lands.

The Supreme Court of the United States, under Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (1836–1864), issued several important decisions on the status of aboriginal title in the United States, building on the opinions of aboriginal title in the Marshall Court.