A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostages, unnecessarily destroying civilian property, deception by perfidy, wartime sexual violence, pillaging, and for any individual that is part of the command structure who orders any attempt to committing mass killings including genocide or ethnic cleansing, the granting of no quarter despite surrender, the conscription of children in the military and flouting the legal distinctions of proportionality and military necessity.

The Burma Railway, also known as the Siam–Burma Railway, Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, or as the Death Railway, is a 415 km (258 mi) railway between Ban Pong, Thailand, and Thanbyuzayat, Burma. It was built from 1940 to 1943 by Southeast Asian civilians abducted and forced to work by the Japanese and a smaller group of captured Allied soldiers, to supply troops and weapons in the Burma campaign of World War II. It completed the rail link between Bangkok, Thailand, and Rangoon, Burma. The name used by the Imperial Japanese Government was Tai–Men Rensetsu Tetsudō (泰緬連接鉄道), which means Thailand-Burma-Link-Railway.

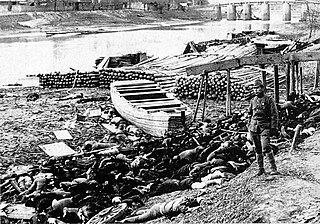

The Bataan Death March was the forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of around 72,000 to 78,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war (POW) from the municipalities of Bagac and Mariveles on the Bataan Peninsula to Camp O'Donnell via San Fernando.

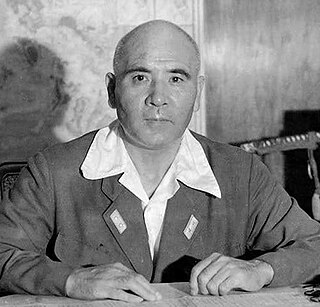

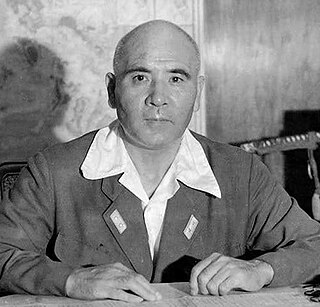

Masaharu Homma was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. Homma commanded the Japanese 14th Army, which invaded the Philippines and perpetrated the Bataan Death March. After the war, Homma was convicted of war crimes relating to the actions of troops under his direct command and executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

The Commando Order was issued by the OKW, the high command of the German Armed Forces, on 18 October 1942. This order stated that all Allied commandos captured in Europe and Africa should be summarily executed without trial, even if in proper uniforms or if they attempted to surrender. Any commando or small group of commandos or a similar unit, agents, and saboteurs not in proper uniforms who fell into the hands of the German forces by some means other than direct combat, were to be handed over immediately to the Sicherheitsdienst for immediate execution.

Disarmed Enemy Forces is a US designation for soldiers who surrender to an adversary after hostilities end, and for those POWs who had already surrendered and were held in camps in occupied German territory at the time. It was General Dwight D. Eisenhower's designation of German prisoners in post–World War II occupied Germany.

A prisoner-of-war camp is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured as prisoners of war by a belligerent power in time of war.

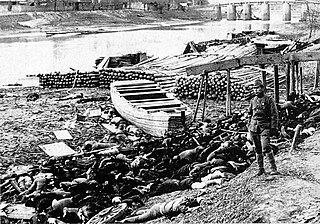

During its imperial era, the Empire of Japan committed numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity across various Asian-Pacific nations, notably during the Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. These incidents have been referred to as "the Asian Holocaust", and "Japan's Holocaust", and also as the "Rape of Asia". The crimes occurred during the early part of the Shōwa era, under Hirohito's reign.

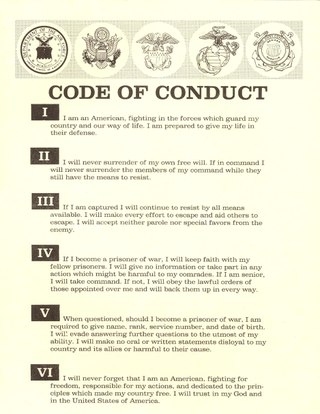

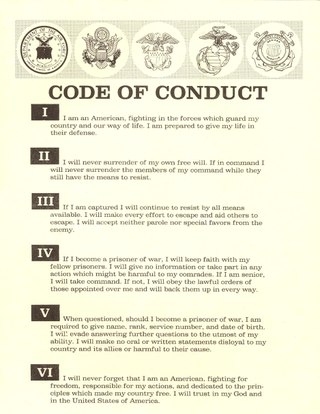

The Code of the U.S. Fighting Force is a code of conduct that is an ethics guide and a United States Department of Defense directive consisting of six articles to members of the United States Armed Forces, addressing how they should act in combat when they must evade capture, resist while a prisoner or escape from the enemy. It is considered an important part of U.S. military doctrine and tradition, but is not formal military law in the manner of the Uniform Code of Military Justice or public international law, such as the Geneva Conventions.

During World War II, the Allies committed legally proven war crimes and violations of the laws of war against either civilians or military personnel of the Axis powers. At the end of World War II, many trials of Axis war criminals took place, most famously the Nuremberg trials and Tokyo Trials. In Europe, these tribunals were set up under the authority of the London Charter, which only considered allegations of war crimes committed by people who acted in the interests of the Axis powers. Some war crimes involving Allied personnel were investigated by the Allied powers and led in some instances to courts-martial. Some incidents alleged by historians to have been crimes under the law of war in operation at the time were, for a variety of reasons, not investigated by the Allied powers during the war, or were investigated but not prosecuted.

The Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War was signed at Geneva, July 27, 1929. Its official name is the Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. It entered into force 19 June 1931. It is this version of the Geneva Conventions which covered the treatment of prisoners of war during World War II. It is the predecessor of the Third Geneva Convention signed in 1949.

There are differences from one country to another regarding the definition of Japanese war crimes. War crimes have been broadly defined as violations of the laws or customs of war, which involves acts using prohibited weapons, violating battlefield norms while engaging in combat with the enemy combatants, or against protected persons, including enemy civilians and citizens and property of neutral states as in the case of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Military personnel from the Empire of Japan have been accused and/or convicted of committing many such acts during the period of Japanese imperialism from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. They have been accused of conducting a series of human rights abuses against civilians and prisoners of war (POWs) throughout east Asia and the western Pacific region. These events reached their height during the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45 and the Asian and Pacific campaigns of World War II (1941–45).

The United States Armed Forces and its members have violated the law of war after the signing of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the signing of the Geneva Conventions. The United States prosecutes offenders through the War Crimes Act of 1996 as well as through articles in the Uniform Code of Military Justice. The United States signed the 1999 Rome Statute but it never ratified the treaty, taking the position that the International Criminal Court (ICC) lacks fundamental checks and balances. The American Service-Members' Protection Act of 2002 further limited US involvement with the ICC. The ICC reserves the right of states to prosecute war crimes, and the ICC can only proceed with prosecution of crimes when states do not have willingness or effective and reliable processes to investigate for themselves. The United States says that it has investigated many of the accusations alleged by the ICC prosecutors as having occurred in Afghanistan, and thus does not accept ICC jurisdiction over its nationals.

During World War II, it was estimated that between 35,000 and 50,000 members of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces surrendered to Allied service members prior to the end of World War II in Asia in August 1945. Also, Soviet troops seized and imprisoned more than half a million Japanese troops and civilians in China and other places. The number of Japanese soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who surrendered was limited by the Japanese military indoctrinating its personnel to fight to the death, Allied combat personnel often being unwilling to take prisoners, and many Japanese soldiers believing that those who surrendered would be killed by their captors.

Soviet prisoners of war in Finland during World War II were captured in two Soviet-Finnish conflicts of that period: the Winter War and the Continuation War. The Finns took about 5,700 POWs during the Winter War, and due to the short length of the war they survived relatively well. However, during the Continuation War the Finns took 64,000 POWs, of whom almost 30 percent died.

Before the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific, the island of Borneo was divided into five territories. Four of the territories were in the north and under British control – Sarawak, Brunei, Labuan, an island, and British North Borneo; while the remainder, and bulk, of the island, was under the jurisdiction of the Dutch East Indies.

During World War II, the Soviet Union committed various atrocities against prisoners of war (POWs). These actions were carried out by the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) and the Red Army. In some cases, the crimes were sanctioned or directly ordered by Joseph Stalin and the Soviet leadership.

During World War II, Nazi Germany committed many atrocities against prisoners of war (POWs). German mistreatment and war crimes against prisoners of war began in the first days of the war during their invasion of Poland, with an estimated 3,000 Polish POWs murdered in dozens of incidents. The treatment of POWs by the Germans varied based on the country; in general, the Germans treated POWs belonging to the Western Allies well, while the opposite was true on the Eastern Front.

Prisoners of war during World War II faced vastly different fates due to the POW conventions adhered to or ignored, depending on the theater of conflict, and the behaviour of their captors. During the war approximately 35 million soldiers surrendered, with many held in the prisoner-of-war camps. Most of the POWs were taken in the European theatre of the war. Approximately 14%, or 5 million, died in captivity.