A commodity market is a market that trades in the primary economic sector rather than manufactured products, such as cocoa, fruit and sugar. Hard commodities are mined, such as gold and oil. Futures contracts are the oldest way of investing in commodities. Commodity markets can include physical trading and derivatives trading using spot prices, forwards, futures, and options on futures. Farmers have used a simple form of derivative trading in the commodities market for centuries for price risk management.

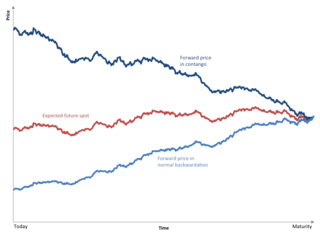

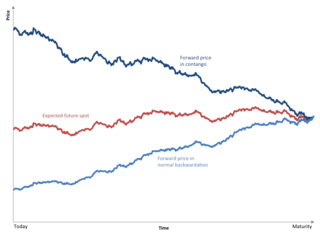

Contango is a situation in which the futures price of a commodity is higher than the expected spot price of the contract at maturity. In a contango situation, arbitrageurs or speculators are "willing to pay more [now] for a commodity [to be received] at some point in the future than the actual expected price of the commodity [at that future point]. This may be due to people's desire to pay a premium to have the commodity in the future rather than paying the costs of storage and carry costs of buying the commodity today." On the other side of the trade, hedgers are happy to sell futures contracts and accept the higher-than-expected returns. A contango market is also known as a normal market or carrying-cost market.

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset with the hope that it will become more valuable shortly. It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hopes for a decline in value.

In finance, a futures contract is a standardized legal contract to buy or sell something at a predetermined price for delivery at a specified time in the future, between parties not yet known to each other. The item transacted is usually a commodity or financial instrument. The predetermined price of the contract is known as the forward price or delivery price. The specified time in the future when delivery and payment occur is known as the delivery date. Because it derives its value from the value of the underlying asset, a futures contract is a derivative.

A hedge is an investment position intended to offset potential losses or gains that may be incurred by a companion investment. A hedge can be constructed from many types of financial instruments, including stocks, exchange-traded funds, insurance, forward contracts, swaps, options, gambles, many types of over-the-counter and derivative products, and futures contracts.

The New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) is a commodity futures exchange owned and operated by CME Group of Chicago. NYMEX is located at One North End Avenue in Brookfield Place in the Battery Park City section of Manhattan, New York City.

Liquidity risk is a financial risk that for a certain period of time a given financial asset, security or commodity cannot be traded quickly enough in the market without impacting the market price.

John Douglas Arnold is an American philanthropist, former Enron executive, and founder of Arnold Ventures LLC, formerly the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. In 2007, Arnold became the youngest billionaire in the U.S. His firm, Centaurus Advisors, LLC, was a Houston-based hedge fund specializing in trading energy products that closed in 2012. He now focuses on philanthropy through Arnold Ventures LLC. Arnold is a board member of Breakthrough Energy Ventures and since February 2024, is a member of the board of directors of Meta.

A commodity broker is a firm or an individual who executes orders to buy or sell commodity contracts on behalf of the clients and charges them a commission. A firm or individual who trades for his own account is called a trader. Commodity contracts include futures, options, and similar financial derivatives. Clients who trade commodity contracts are either hedgers using the derivatives markets to manage risk, or speculators who are willing to assume that risk from hedgers in hopes of a profit.

Brian Hunter is a Canadian former natural gas trader for the now closed Amaranth Advisors hedge fund. Amaranth had over $9 billion in assets but collapsed in 2006 after Hunter's gamble on natural gas futures market went bad.

MotherRock was an energy sector hedge fund, one of the biggest traders of natural gas derivatives in New York, with assets of around $430 million at one point. It closed in August 2006 due losing money on its bets that natural gas prices would fall. In 2006 the summer heat led to prices increasing and in June 2006 MotherRock Energy Fund lost 24.6 percent and then in July 25.5 percent. Leveraged positions exacerbated the situation and eventually led to a loss of around $230 million in June and July 2006.

Moore Capital Management, LP (MCM) is a global investment management firm headquartered in New York, New York. In September 2018, MCM had $10.2 billion in total assets under management.

The May 6, 2010, flash crash, also known as the crash of 2:45 or simply the flash crash, was a United States trillion-dollar flash crash which started at 2:32 p.m. EDT and lasted for approximately 36 minutes.

A commodity trading advisor (CTA) is US financial regulatory term for an individual or organization who is retained by a fund or individual client to provide advice and services related to trading in futures contracts, commodity options and/or swaps. They are responsible for the trading within managed futures accounts. The definition of CTA may also apply to investment advisors for hedge funds and private funds including mutual funds and exchange-traded funds in certain cases. CTAs are generally regulated by the United States federal government through registration with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and membership of the National Futures Association (NFA).

A managed futures account (MFA) or managed futures fund (MFF) is a type of alternative investment in the US in which trading in the futures markets is managed by another person or entity, rather than the fund's owner. Managed futures accounts include, but are not limited to, commodity pools. These funds are operated by commodity trading advisors (CTAs) or commodity pool operators (CPOs), who are generally regulated in the United States by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the National Futures Association. As of June 2016, the assets under management held by managed futures accounts totaled $340 billion.

Spoofing is a disruptive algorithmic trading activity employed by traders to outpace other market participants and to manipulate markets. Spoofers feign interest in trading futures, stocks, and other products in financial markets creating an illusion of the demand and supply of the traded asset. In an order driven market, spoofers post a relatively large number of limit orders on one side of the limit order book to make other market participants believe that there is pressure to sell or to buy the asset.

William O. Perkins III is an American hedge fund manager and poker player. Perkins manages Skylar Capital, an energy trading hedge fund that had approximately $500 million in assets under management as of 2023.

Securities market participants in the United States include corporations and governments issuing securities, persons and corporations buying and selling a security, the broker-dealers and exchanges which facilitate such trading, banks which safe keep assets, and regulators who monitor the markets' activities. Investors buy and sell through broker-dealers and have their assets retained by either their executing broker-dealer, a custodian bank or a prime broker. These transactions take place in the environment of equity and equity options exchanges, regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), or derivative exchanges, regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). For transactions involving stocks and bonds, transfer agents assure that the ownership in each transaction is properly assigned to and held on behalf of each investor.

Verition Fund Management (Verition) is an American multi-strategy hedge fund management firm headquartered in Greenwich, Connecticut. It has additional offices in Europe and Asia.

Jon Paul Ruggles is an American executive known for founding Monroe Energy and creating an internal trading house that enabled Delta Air Lines to control its fuel supply. According to CNBC, Delta hired Ruggles as vice-president of fuel in 2011 to help right a fuel-hedge book that had been losing the airline money. He managed to generate notable trading returns.