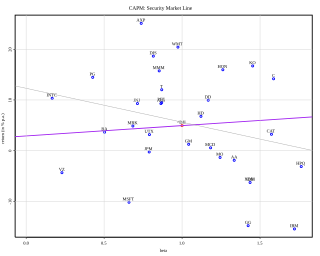

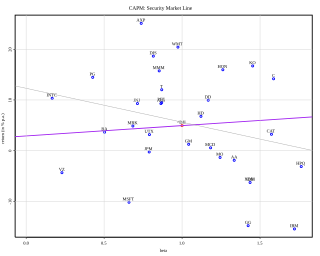

In finance, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) is a model used to determine a theoretically appropriate required rate of return of an asset, to make decisions about adding assets to a well-diversified portfolio.

In statistics, the Gauss–Markov theorem states that the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimator has the lowest sampling variance within the class of linear unbiased estimators, if the errors in the linear regression model are uncorrelated, have equal variances and expectation value of zero. The errors do not need to be normal, nor do they need to be independent and identically distributed. The requirement that the estimator be unbiased cannot be dropped, since biased estimators exist with lower variance. See, for example, the James–Stein estimator, ridge regression, or simply any degenerate estimator.

In mathematical finance, the Greeks are the quantities representing the sensitivity of the price of a derivative instrument such as an option to changes in one or more underlying parameters on which the value of an instrument or portfolio of financial instruments is dependent. The name is used because the most common of these sensitivities are denoted by Greek letters. Collectively these have also been called the risk sensitivities, risk measures or hedge parameters.

Modern portfolio theory (MPT), or mean-variance analysis, is a mathematical framework for assembling a portfolio of assets such that the expected return is maximized for a given level of risk. It is a formalization and extension of diversification in investing, the idea that owning different kinds of financial assets is less risky than owning only one type. Its key insight is that an asset's risk and return should not be assessed by itself, but by how it contributes to a portfolio's overall risk and return. The variance of return is used as a measure of risk, because it is tractable when assets are combined into portfolios. Often, the historical variance and covariance of returns is used as a proxy for the forward-looking versions of these quantities, but other, more sophisticated methods are available.

In finance, arbitrage pricing theory (APT) is a multi-factor model for asset pricing which relates various macro-economic (systematic) risk variables to the pricing of financial assets. Proposed by economist Stephen Ross in 1976, it is widely believed to be an improved alternative to its predecessor, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). APT is founded upon the law of one price, which suggests that within an equilibrium market, rational investors will implement arbitrage such that the equilibrium price is eventually realised. As such, APT argues that when opportunities for arbitrage are exhausted in a given period, then the expected return of an asset is a linear function of various factors or theoretical market indices, where sensitivities of each factor is represented by a factor-specific beta coefficient or factor loading. Consequently, it provides traders with an indication of ‘true’ asset value and enables exploitation of market discrepancies via arbitrage. The linear factor model structure of the APT is used as the basis for evaluating asset allocation, the performance of managed funds as well as the calculation of cost of capital. Furthermore, the newer APT model is more dynamic being utilised in more theoretical application than the preceding CAPM model. A 1986 article written by Gregory Connor and Robert Korajczyk, utilised the APT framework and applied it to portfolio performance measurement suggesting that the Jensen coefficient is an acceptable measurement of portfolio performance.

In finance, the duration of a financial asset that consists of fixed cash flows, such as a bond, is the weighted average of the times until those fixed cash flows are received. When the price of an asset is considered as a function of yield, duration also measures the price sensitivity to yield, the rate of change of price with respect to yield, or the percentage change in price for a parallel shift in yields.

In finance, Jensen's alpha is used to determine the abnormal return of a security or portfolio of securities over the theoretical expected return. It is a version of the standard alpha based on a theoretical performance instead of a market index.

In statistics, econometrics, epidemiology and related disciplines, the method of instrumental variables (IV) is used to estimate causal relationships when controlled experiments are not feasible or when a treatment is not successfully delivered to every unit in a randomized experiment. Intuitively, IVs are used when an explanatory variable of interest is correlated with the error term (endogenous), in which case ordinary least squares and ANOVA give biased results. A valid instrument induces changes in the explanatory variable but has no independent effect on the dependent variable and is not correlated with the error term, allowing a researcher to uncover the causal effect of the explanatory variable on the dependent variable.

In statistics, ordinary least squares (OLS) is a type of linear least squares method for choosing the unknown parameters in a linear regression model by the principle of least squares: minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed dependent variable in the input dataset and the output of the (linear) function of the independent variable. Some sources consider OLS to be linear regression.

In statistics, simple linear regression (SLR) is a linear regression model with a single explanatory variable. That is, it concerns two-dimensional sample points with one independent variable and one dependent variable and finds a linear function that, as accurately as possible, predicts the dependent variable values as a function of the independent variable. The adjective simple refers to the fact that the outcome variable is related to a single predictor.

In statistics, the delta method is a method of deriving the asymptotic distribution of a random variable. It is applicable when the random variable being considered can be defined as a differentiable function of a random variable which is asymptotically Gaussian.

In statistics, generalized least squares (GLS) is a method used to estimate the unknown parameters in a linear regression model. It is used when there is a non-zero amount of correlation between the residuals in the regression model. GLS is employed to improve statistical efficiency and reduce the risk of drawing erroneous inferences, as compared to conventional least squares and weighted least squares methods. It was first described by Alexander Aitken in 1935.

Security market line (SML) is the representation of the capital asset pricing model. It displays the expected rate of return of an individual security as a function of systematic, non-diversifiable risk. The risk of an individual risky security reflects the volatility of the return from the security rather than the return of the market portfolio. The risk in these individual risky securities reflects the systematic risk.

The single-index model (SIM) is a simple asset pricing model to measure both the risk and the return of a stock. The model has been developed by William Sharpe in 1963 and is commonly used in the finance industry. Mathematically the SIM is expressed as:

Fixed-income attribution is the process of measuring returns generated by various sources of risk in a fixed income portfolio, particularly when multiple sources of return are active at the same time.

In corporate finance, Hamada’s equation is an equation used as a way to separate the financial risk of a levered firm from its business risk. The equation combines the Modigliani–Miller theorem with the capital asset pricing model. It is used to help determine the levered beta and, through this, the optimal capital structure of firms. It was named after Robert Hamada, the Professor of Finance behind the theory.

In statistics, principal component regression (PCR) is a regression analysis technique that is based on principal component analysis (PCA). More specifically, PCR is used for estimating the unknown regression coefficients in a standard linear regression model.

In investing, downside beta is the beta that measures a stock's association with the overall stock market (risk) only on days when the market’s return is negative. Downside beta was first proposed by Roy 1952 and then popularized in an investment book by Markowitz (1959).

In investing, upside beta is the element of traditional beta that investors do not typically associate with the true meaning of risk. It is defined to be the scaled amount by which an asset tends to move compared to a benchmark, calculated only on days when the benchmark's return is positive.

Untradable assets are assets that are not traded on the market. Human capital is the most important nontraded assets. Other important nontraded asset classes are private businesses, claims to government transfer payments and claims on trust income.