Interactive fiction (IF) is software simulating environments in which players use text commands to control characters and influence the environment. Works in this form can be understood as literary narratives, either in the form of Interactive narratives or Interactive narrations. These works can also be understood as a form of video game, either in the form of an adventure game or role-playing game. In common usage, the term refers to text adventures, a type of adventure game where the entire interface can be "text-only", however, graphical text adventure games, where the text is accompanied by graphics still fall under the text adventure category if the main way to interact with the game is by typing text. Some users of the term distinguish between interactive fiction, known as "Puzzle-free", that focuses on narrative, and "text adventures" that focus on puzzles.

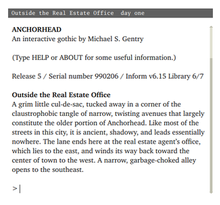

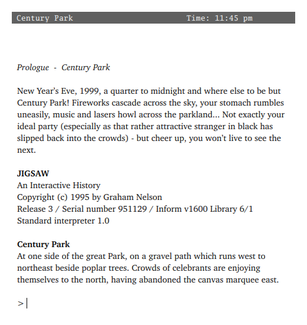

Inform is a programming language and design system for interactive fiction originally created in 1993 by Graham Nelson. Inform can generate programs designed for the Z-code or Glulx virtual machines. Versions 1 through 5 were released between 1993 and 1996. Around 1996, Nelson rewrote Inform from first principles to create version 6. Over the following decade, version 6 became reasonably stable and a popular language for writing interactive fiction. In 2006, Nelson released Inform 7, a completely new language based on principles of natural language and a new set of tools based around a book-publishing metaphor.

Graham A. Nelson is a British mathematician, poet, and the creator of the Inform design system for creating interactive fiction (IF) games. He has authored several IF games, including Curses (1993) and Jigsaw (1995).

Photopia is a piece of literature by Adam Cadre rendered in the form of interactive fiction, and written in Inform. It has received both praise and criticism for its heavy focus on fiction rather than on interactivity. It won first place in the 1998 Interactive Fiction Competition. Photopia has few puzzles and a linear structure, allowing the player no way to alter the eventual conclusion but maintaining the illusion of non-linearity.

Andrew Plotkin, also known as Zarf, is a central figure in the modern interactive fiction (IF) community. Having both written a number of award-winning games and developed a range of new file formats, interpreters, and other utilities for the design, production, and running of IF games, Plotkin is widely recognised for both his creative and his technical contributions to the homebrew IF scene.

The XYZZY Awards are the annual awards given to works of interactive fiction, serving a similar role to the Academy Awards for film. The awards were inaugurated in 1997 by Eileen Mullin, the editor of XYZZYnews. Any game released during the year prior to the award ceremony is eligible for nomination to receive an award. The decision process takes place in two stages: members of the interactive fiction community nominate works within specific categories and sufficiently supported nominations become finalists within those categories. Community members then vote among the finalists, and the game receiving a plurality of votes is given the award in an online ceremony.

Blue Chairs is an interactive fiction game by American author Chris Klimas.

Emily Short is an interactive fiction (IF) writer. From 2020 to 2023, she was creative director of Failbetter Games, the studio behind Fallen London and its spinoffs.

Lovecraftian horror, also called cosmic horror or eldritch horror, is a subgenre of horror, fantasy fiction and weird fiction that emphasizes the horror of the unknowable and incomprehensible more than gore or other elements of shock. It is named after American author H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937). His work emphasizes themes of cosmic dread, forbidden and dangerous knowledge, madness, non-human influences on humanity, religion and superstition, fate and inevitability, and the risks associated with scientific discoveries, which are now associated with Lovecraftian horror as a subgenre. The cosmic themes of Lovecraftian horror can also be found in other media, notably horror films, horror games, and comics.

"From Beyond" is a horror genre short story by American writer H. P. Lovecraft. It was written in 1920 and was first published in The Fantasy Fan in June 1934.

Jon Ingold is a British author of interactive fiction and co-founder of inkle, where he co-directed and co-wrote 80 Days, and wrote Heaven's Vault and Overboard!. His interactive fiction has frequently been nominated for XYZZY Awards and has won on multiple occasions, including Best Game, Best Story and Best Setting awards for All Roads in 2001. Ingold's works are notable for their attention to the levels of knowledge that the player and player character have of the in-game situation, with the effect often depending on a player who understands more than the character or vice versa. Ingold has also written a number of plays, short stories and novels.

Vespers is an interactive fiction game written in 2005 by Jason Devlin that placed first at the 2005 Interactive Fiction Competition. It also won the XYZZY Awards for Best Game, Best NPCs, Best Setting, and Best Writing.

Jigsaw is an interactive fiction (IF) game, written by Graham Nelson in 1995.

Aisle is a 1999 interactive fiction video game whose major innovation is to allow only a single move and offer from it over a hundred possible outcomes. It is notable for introducing and popularizing the one move genre.

Cryptozookeeper is an interactive fiction game written and self-published by American developer Robb Sherwin in 2011. Cryptozookeeper was written in the cross-platform language Hugo and runs on Windows, Macintosh OS-X, and Linux computers. Cryptozookeeper was released under a Creative Commons license and contains more than 12 hours of game play.

The Shore is a Lovecraftian horror exploration and adventure video game developed by Greek indie developer Ares Dragonis. The game takes place on a remote, mysterious island, where the protagonist is searching for his missing daughter.

Snack Time! is a 2008 interactive fiction work by Renee Choba, which she co-authored with Hardy the Bulldog, who also features as the player character (PC). Snack Time! presents the interactor with the challenge of getting a snack while playing as Hardy the Bulldog. Hardy must complete a series of steps, each of the five steps worth ten points, making a score of 50 possible, in order to get the sandwich from the human owner. Taking place within just a few rooms of living space, the interactor must position themselves from a dog's perspective in order to successfully complete the game.

Counterfeit Monkey is a 2012 interactive fiction espionage game by Emily Short.

The Interactive Fiction Database (IFDB) is a database of metadata and reviews of interactive fiction.

The Wizard Sniffer is a 2017 interactive fiction fantasy comedy game by Buster Hudson.