Anne Greene (c. 1628 –1659 or c. 1665) was an English domestic servant who was accused of committing infanticide in 1650. She is known for surviving her attempted execution by hanging, being revived by physicians from the University of Oxford.

Anne Greene (c. 1628 –1659 or c. 1665) was an English domestic servant who was accused of committing infanticide in 1650. She is known for surviving her attempted execution by hanging, being revived by physicians from the University of Oxford.

Greene was born around 1628 in Steeple Barton, Oxfordshire. In her early adulthood, she worked as a scullery maid in the house of Sir Thomas Reade, a justice of the peace who lived in nearby Duns Tew. She later claimed that in 1650 when she was a 22-year-old servant, she was seduced by Sir Thomas's grandson, Geoffrey Reade, who was 16 or 17 years old. [1] [2]

She became pregnant, though she later claimed that she was not aware of her pregnancy until she miscarried in the privy [3] after seventeen weeks. [4] She tried to conceal the remains of the fetus [2] but was discovered and suspected of infanticide. Sir Thomas prosecuted Greene [4] under the Concealment of Birth of Bastards Act 1624 (21 Jas. 1. c. 27), under which there was a legal presumption that a woman who concealed the death of her illegitimate child had murdered the child. [5]

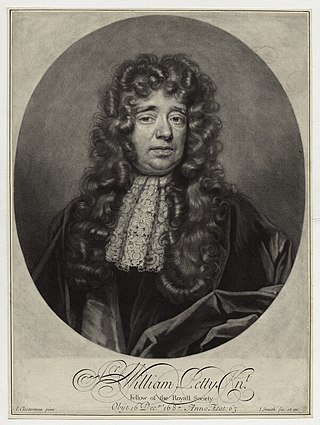

A midwife testified that the fetus was too underdeveloped to have ever been alive, and several servants who worked with Greene testified that she had experienced "issues" for approximately one month before her miscarriage, which began after she laboured turning malt. [6] [7] In spite of the testimony, Greene was found guilty of murder and was hanged at Oxford Castle on 14 December 1650. At her own request, several of her friends pulled her swinging body and a soldier struck her four or five times with the butt of his musket [8] to expedite her death. [9] She was presumed dead half an hour later, so she was cut down and given to University of Oxford physicians William Petty and Thomas Willis for dissection. [10]

The physicians opened Greene's coffin on the morning of her hanging [9] and discovered that she had a faint pulse and was weakly breathing. Petty and Willis sought the help of their Oxford colleagues Ralph Bathurst and Henry Clerke. [9] [10] The group of physicians tried many remedies to revive Greene, including pouring hot cordial down her throat, rubbing her limbs and extremities, bloodletting, applying a poultice to her breasts, and administering a tobacco smoke enema. [11] The physicians then placed her in a warm bed with another woman, who rubbed her and kept her warm. Greene began to recover quickly, beginning to speak after twelve [12] to fourteen hours [13] of treatment and eating solid food after four days. Within one month she had fully recovered, aside from amnesia about the time surrounding her execution. [12]

The authorities granted Greene a reprieve from execution while she recovered and ultimately pardoned her, believing that the hand of God had saved her, demonstrating her innocence. [10] Furthermore, one pamphleteer notes that Sir Thomas Reade died three days after Greene's hanging, so there was no prosecutor to object to the pardon. [6] However, another pamphleteer writes that her recovery "moved some of her enemies to wrath and indignation, insomuch that a great man amongst the rest, moved to have her again carried to the place of execution, to be hanged up by the neck, contrary to all Law, reason and justice; but some honest Souldiers then present seemed to be very much discontent thereat" and intervened on Greene's behalf. [14]

After her recovery, Greene went to stay with friends in the country, taking the coffin with her. She married and had three children. Robert Plot's 1677 The Natural History of Oxfordshire claims that she died in 1659, [3] [15] while Petty claimed that Greene lived fifteen years after her hanging, dying c. 1665, according to a 1675 entry in John Evelyn's Diary . [12] [16]

The event inspired two 17th-century pamphlets. The first, by W. Burdet, was entitled A Wonder of Wonders (Oxford, 1651) in its first edition and A Declaration from Oxford, of Anne Greene in its second edition. Burdet's pamphlets portray the event in miraculous, metaphysical terms. In 1651, Richard Watkins also published a pamphlet containing a sober, medically accurate prose account of the event and poems inspired by it, entitled Newes from the Dead (Oxford: Leonard Lichfield, 1651). The poems, of which there were 25 in various languages, included a set of English verses by Christopher Wren, who was at that time a gentleman-commoner (a student who paid all fees in advance) of Wadham College. [17]

Greene's story was also mentioned in the 1659 English edition of Denis Pétau's The History of the World and in Robert Plot's 1677 The Natural History of Oxfordshire. [15]

1650 (MDCL) was a common year starting on Saturday of the Gregorian calendar and a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar, the 1650th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 650th year of the 2nd millennium, the 50th year of the 17th century, and the 1st year of the 1650s decade. As of the start of 1650, the Gregorian calendar was 10 days ahead of the Julian calendar, which remained in localized use until 1923.

Sir William Petty was an English economist, physician, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth in Ireland. He developed efficient methods to survey the land that was to be confiscated and given to Cromwell's soldiers. He also remained a significant figure under King Charles II and King James II, as did many others who had served Cromwell.

Lucy Walter, also known as Lucy Barlow, was the first mistress of King Charles II of England and mother of James, Duke of Monmouth. During the Exclusion Crisis, a Protestant faction wanted to make her son heir to the throne, fuelled by the rumour that the king might have married Lucy, a claim which he denied.

Nathaniel Fiennes, c. 1608 to 16 December 1669, was a younger son of the Puritan nobleman and politician, William Fiennes, 1st Viscount Saye and Sele. He sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1640 and 1659, and served with the Parliamentarian army in the First English Civil War. In 1643, he was dismissed from the army for alleged incompetence after surrendering Bristol and sentenced to death before being pardoned. Exonerated in 1645, he actively supported Oliver Cromwell during The Protectorate, being Lord Keeper of the Great Seal from 1655 to 1659.

Duns Tew is an English village and civil parish about 7+1⁄2 miles (12 km) south of Banbury in Oxfordshire. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 478. With nearby Great Tew and Little Tew, Duns Tew is one of the three villages known collectively as "The Tews". A 'tew' is believed to be an ancient term for a ridge of land.

Events from the year 1650 in England, second year of the Third English Civil War.

Anne, Lady Fairfax was an English noblewoman. She was the wife of Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron, commander-in-chief of the New Model Army. She followed her husband as he fought and she was briefly taken prisoner. It is said that she was ejected after heckling the court at the trial of Charles I.

Ralph Bathurst, FRS was an English theologian and physician.

John Wilde was an English lawyer and politician. As a serjeant-at-law he was referred to as Serjeant Wilde before he was appointed judge. He was a judge, chief baron of the exchequer, and member of the Council of State of the Commonwealth period.

Nathan Paget was an English physician, active during the English Civil War, under the Commonwealth and the Protectorate, and after the Restoration. Despite being a mainstay of a generally conservative profession, he was interested in the experimental methods of the Enlightenment. Although from a strongly Presbyterian background, he seems to have developed radical political and religious sympathies.

James Primrose or Primerose M.D. was an English physician, an opponent of William Harvey's theory of the circulation of the blood.

Thomas Cooper was a colonel in the Parliamentary Army who fought in the English Civil War and aided in the Cromwellian occupation of Ireland. He was appointed to the Cromwell's Upper House, and died in 1659.

Eusebius Andrews, December 1606 to 22 August 1650, was a London lawyer and Royalist during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, executed for his part in a 1650 plot to restore Charles II of England. A prominent supporter of the Crown since the early 1630s, he was a determined conspirator who organised a number of Royalist risings in Cambridgeshire between 1642 and 1650.

Anne Dormer, was an English letter writer. She was the spouse of Robert Dormer (1628?–1689) of Rousham in Oxfordshire. Her correspondence with her sister Elizabeth has been used in several recent histories on the domestic concerns of seventeenth century women and their legal and romantic relationships with men.

Steeple Barton is a civil parish and scattered settlement on the River Dorn in West Oxfordshire, about 8+1⁄2 miles (13.7 km) east of Chipping Norton, a similar distance west of Bicester and 9 miles (14 km) south of Banbury. Most of the parish's population lives in the village of Middle Barton, about 1 mile (1.6 km) northwest of the settlement of Steeple Barton. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 1,523. Much of the parish's eastern boundary is formed by the former turnpike between Oxford and Banbury, now classified the A4260 road. The minor road between Middle Barton and Kiddington forms part of the western boundary. Field boundaries form most of the rest of the boundaries of the parish.

Sir James Dashwood, 2nd Baronet was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1740 to 1768.

The Proceedings between Sankey and Petty is a pamphlet that contains a summary of the controversy that arose between Sir Hierom Sankey and Sir William Petty in the aftermath of the Down Survey. Sankey accused Petty of bribery and fraud. One of the ways in which Petty answered to this accusations was by this pamphlet, that was published in print by Petty in 1659 and covers a total of ten pages.

Henry Beeston was an English educator.

Mary Lakeland also known as Mother Lakeland and the “Ipswich Witch”, was an English woman executed for witchcraft in Ipswich. She belonged to the few people in England to have been executed by burning after a conviction of witchcraft. She was the last person executed for witchcraft in the town of Ipswich.