The Tiananmen Square protests, known in Chinese as the June Fourth Incident, were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square, Beijing during 1989. In what is known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or in Chinese the June Fourth Clearing or June Fourth Massacre, troops armed with assault rifles and accompanied by tanks fired at the demonstrators and those trying to block the military's advance into Tiananmen Square. The protests started on 15 April and were forcibly suppressed on 4 June when the government declared martial law and sent the People's Liberation Army to occupy parts of central Beijing. Estimates of the death toll vary from several hundred to several thousand, with thousands more wounded. The popular national movement inspired by the Beijing protests is sometimes called the '89 Democracy Movement or the Tiananmen Square Incident.

Chai Ling is a Chinese psychologist who was one of the student leaders in the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. She is the founder of All Girls Allowed, an organization dedicated to ending China's one-child policy, and the founder and president of Jenzabar, an enterprise resource planning software firm for educational institutions.

The Goddess of Democracy, also known as the Goddess of Democracy and Freedom, the Spirit of Democracy, and the Goddess of Liberty, was a 10-metre-tall (33 ft) statue created during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. The statue was constructed over four days out of foam and papier-mâché over a metal armature and was unveiled and erected on Tiananmen Square on May 30, 1989. The constructors decided to make the statue as large as possible to try to dissuade the government from dismantling it: the government would either have to destroy the statue—an action which would potentially fuel further criticism of its policies—or leave it standing. Nevertheless, the statue was destroyed on June 4, 1989, by soldiers clearing the protesters from Tiananmen square. Since its destruction, numerous replicas and memorials have been erected around the world, including in Hong Kong, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Vancouver.

Chen Xitong was a member of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party and the Mayor of Beijing until he was removed from office on charges of corruption in 1995.

Yao Yilin was a Vice Premier of the People's Republic of China from 1979 to 1988, and the country's First Vice Premier from 1988 to 1993.

In the days following the end of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, several memorials and vigils were held around the world for those who were killed in the demonstrations. Since then, annual memorials have been held in places outside of Mainland China, most notably in Hong Kong, Taiwan and the United States.

The 21st anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre began as a small march to commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in Hong Kong. Hong Kong and Macau are the only places on Chinese soil where the 1989 crushing of China's pro-democracy movement can be commemorated, and the annual event to commemorate has been taking place in Hong Kong since 1990.

The 10th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre (10周年六四遊行) was a series of rallies – street marches, parades, and candlelight vigils – that took place in late May to early June 1999 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of 4 June 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. The anniversary of the event, during which the Chinese government sent troops to suppress pro-democracy movement and many people are thought to have perished, is remembered around the world in public open spaces and in front of many Chinese embassies in Western countries. On Chinese soil, any mention of the event is completely taboo in Mainland China; events which mark it only take place in Hong Kong, and in Macao to a much lesser extent.

During the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, many big-character posters, banners and leaflets appeared. These posters and leaflets became an important source throughout the course of the student movement. They provided valuable information and insight into the goals, slogans and instructions that were to guide students about what they were expected to do during the protests. A central place where posters and leaflets were printed and posted was at "the Triangle;" located at Peking University. The Triangle, also known as a democracy wall was "a wall of bulletin boards erected around a triangle of land in the centre of the campus". The Triangle became a democratic space where students, teachers and Chinese citizens went in order to voice their opinions and feelings towards the movement, to know the progress and course of the movement, and to provide information on events and incidents. The Triangle was considered "a marketplace for information and was regarded as a symbolic space for free expression."

The April 26 Editorial was a front-page article published in People's Daily on April 26, 1989, during the Tiananmen Square protests. The editorial effectively defined the student movement as a destabilizing anti-party revolt that should be resolutely opposed at all levels of society. As the first authoritative document from the top leadership on the growing movement, it was widely interpreted as having communicated the party's position of "no-tolerance" to student protesters and their sympathizers.

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were the first of their type shown in detail on Western television. The Chinese government's response was denounced, particularly by Western governments and media. Criticism came from both Western and Eastern Europe, North America, Australia and some east Asian and Latin American countries. Notably, many Asian countries remained silent throughout the protests; the government of India responded to the massacre by ordering the state television to pare down the coverage to the barest minimum, so as not to jeopardize a thawing in relations with China, and to offer political empathy for the events. North Korea, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany, among others, supported the Chinese government and denounced the protests. Overseas Chinese students demonstrated in many cities in Europe, America, the Middle East, and Asia against the Chinese government.

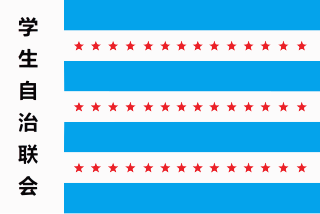

The Beijing Students' Autonomous Federation was a self-governing student organization, representing multiple Beijing universities, and acting as the student protesters' principal decision-making body during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. Student protesters founded the Federation in opposition to the official, government-supported student organizations, which they believed were undemocratic. Although the Federation made several demands of the government during the protests and organized multiple demonstrations in the Square, its primary focus was to obtain government recognition as a legitimate organization. By seeking this recognition, the Federation directly challenged the Chinese Communist Party's authority. After failing to achieve direct dialogue with the government, the Federation lost support from student protesters, and its central leadership role within the Tiananmen Square protests.

Yan Mingfu is a retired Chinese politician. His first prominent role in government began in 1985, when he was made leader of the United Front Work Department for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He held the position until the CCP expelled him for inadequately following the party line in his dialogues with students during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. Yan returned to government work in 1991 when he became a vice minister of Civil Affairs.

Defend Tiananmen Square Headquarters was formed on May 24, 1989. The purpose of this organization was to create a strong leadership to lead the student movement.

The People's Daily is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, providing direct information on the policies and positions of the government to its readers. During the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, People's Daily played an important role in changing the course of events, especially its April 26 Editorial that provoked great tension between the government and the students when the movement was slowly abating after Hu Yaobang's memorial on April 25. As an official newspaper, its attitude toward the government and the student protestors changed multiple times as the newspaper leadership team had to balance between reporting the truth and staying in line with its higher authority, the Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party, according to the then deputy chief editor, Lu Chaoqi.

During the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 in Beijing, China, students demanded a dialogue between Chinese government officials and student representatives. In total, three sessions of dialogue took place between the students and government representatives.

The catalyst for the birth of the Pro-Democracy Movement was the death of Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989. Beginning in late April until June 3 large crowds gathered in Tiananmen Square. During this period a significant amount of money was donated to the student organizations, it was spent on providing food, water and other supplies required to sustain the many thousands of protesters who occupied the Square.

Many women participated in the Tiananmen Square Protests of 1989 for democratic reform in China. Lee Feigon states "women [during the Tiananmen Square Protests] were relegated for the most part to traditional support roles." Chai Ling and Wang Chaohua, however, were female student leaders taking part in leadership activities during the pro-democracy movement. Ranging from student leaders to intellectuals, many women contributed their opinions and leadership skills to the movement. Although women had substantial roles, they had different standpoints regarding the hunger strike movement on May 13.

The first of two student hunger strikes during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre began on May 13, 1989, in Beijing. The students said that they were willing to risk their lives to gain the government's attention. They believed that because plans were in place for the grand welcoming of Mikhail Gorbachev, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, on May 15, at Tiananmen Square, the government would respond. Although the students gained a dialogue session with the government on May 14, no rewards materialized. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) did not heed the students' demands and moved the welcome ceremony to the airport.

The protests that occurred throughout the People's Republic of China in the early to middle months of 1989 mainly started out as memorials for former General Secretary Hu Yaobang. The political fall of Hu came immediately following the 1986 Chinese Student Demonstrations when he was removed by paramount leader Deng Xiaoping for being too liberal in his policies. Upon Hu's death on April 15, 1989, large gatherings of people began forming across the country. Most media attention was put onto the Beijing citizens who participated in the Tiananmen Square Protests, however, every other region in China had cities with similar demonstrations. The origins of these movements gradually became forgotten in some places and some regions began to demonstrate based on their own problems with their Provincial and Central Governments.