Related Research Articles

Li Peng was a Chinese politician who served as the fourth Premier of the People's Republic of China from 1987 to 1998, and as the Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, China's top legislative body, from 1998 to 2003. For much of the 1990s Li was ranked second in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) hierarchy behind then Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin. He retained his seat on the CCP Politburo Standing Committee until his retirement in 2002.

The Tiananmen Square protests, known in Chinese as the June Fourth Incident, were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, during 1989. In what is known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or in Chinese the June Fourth Clearing or June Fourth Massacre, troops armed with assault rifles and accompanied by tanks fired at the demonstrators and those trying to block the military's advance into Tiananmen Square. The protests started on 15 April and were forcibly suppressed on 4 June when the government declared martial law and sent the People's Liberation Army to occupy parts of central Beijing. Estimates of the death toll vary from several hundred to several thousand, with thousands more wounded. The popular national movement inspired by the Beijing protests is sometimes called the '89 Democracy Movement or the Tiananmen Square Incident.

Hu Qili is a former high-ranking politician of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He was a member of the CCP Politburo Standing Committee and a member of its Secretariat between 1987 and 1989. In 1989, he was purged because of his sympathy toward the students of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and his support for General Secretary Zhao Ziyang. However, he was able to get back into politics in 1991. In 2001, he was named chairman of the Soong Ching-ling Foundation.

Shen Tong is an American impact investor, activist, and writer. He founded business accelerators FoodFutureCo in 2015 and Food-X in 2014, the latter of which is recognized by Fast Company as one of "The World's Top 10 Most Innovative Companies of 2015 in Food". He was a Chinese dissident who was exiled as one of the student leaders in the democracy movement at Tiananmen Square in 1989. Shen was one of the People of the Year in Newsweek 1989, and he became a media, software, social entrepreneur, and investor in the late 1990s. He serves on the board of Food Tank.

Chen Xitong was a member of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party and the Mayor of Beijing until he was removed from office on charges of corruption in 1995.

Xiong Yan is a Chinese-American human rights activist, military officer, and Protestant chaplain. He was a dissident involved in 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. Xiong Yan studied at Peking University Law School from 1986–1989. He came to the United States of America as a political refugee in 1992, and later became a chaplain in U.S. Army, serving in Iraq. Xiong Yan is the author of three books, and has earned six degrees. He ran for Congress in New York's 10th congressional district in 2022, and his campaign was reportedly attacked by agents of Communist China's Ministry of State Security.

Almost a Revolution is an autobiography by Shen Tong (沈彤), one of the student leaders during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in Beijing, China, written with former The Washington Post writer Marianne Yen.

Yao Yilin was a Vice Premier of the People's Republic of China from 1979 to 1988, and the country's First Vice Premier from 1988 to 1993.

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were the first of their type shown in detail on Western television. The Chinese government's response was denounced, particularly by Western governments and media. Criticism came from both Western and Eastern Europe, North America, Australia and some east Asian and Latin American countries. Notably, many Asian countries remained silent throughout the protests; the government of India responded to the massacre by ordering the state television to pare down the coverage to the barest minimum, so as not to jeopardize a thawing in relations with China, and to offer political empathy for the events. North Korea, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany, among others, supported the Chinese government and denounced the protests. Overseas Chinese students demonstrated in many cities in Europe, America, the Middle East, and Asia against the Chinese government.

Örkesh Dölet is a political commentator known for his leading role during the Tiananmen protests of 1989.

The Beijing Students' Autonomous Federation was a self-governing student organization, representing multiple Beijing universities, and acting as the student protesters' principal decision-making body during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. Student protesters founded the Federation in opposition to the official, government-supported student organizations, which they believed were undemocratic. Although the Federation made several demands of the government during the protests and organized multiple demonstrations in the Square, its primary focus was to obtain government recognition as a legitimate organization. By seeking this recognition, the Federation directly challenged the Chinese Communist Party's authority. After failing to achieve direct dialogue with the government, the Federation lost support from student protesters, and its central leadership role within the Tiananmen Square protests.

Yan Mingfu is a retired Chinese politician. His first prominent role in government began in 1985, when he was made leader of the United Front Work Department for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He held the position until the CCP expelled him for inadequately following the party line in his dialogues with students during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. Yan returned to government work in 1991 when he became a vice minister of Civil Affairs.

The April 27 demonstrations were massive student protest marches throughout major cities in China during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. The students were protesting in response to the April 26 Editorial published by the People's Daily the previous day. The editorial asserted that the student movement was anti-party and contributed to a sense of chaos and destabilization. The content of the editorial incited the largest student protest of the movement thus far in Beijing: 50,000–200,000 students marched through the streets of Beijing before finally breaking through police lines into Tiananmen Square.

Defend Tiananmen Square Headquarters was formed on May 24, 1989. The purpose of this organization was to create a strong leadership to lead the student movement.

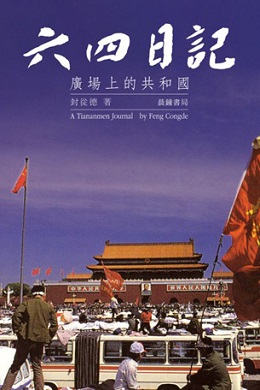

A Tiananmen Journal: Republic on the Square by Feng Congde (封从德) was first published in May 2009 in Hong Kong. This book records the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre from April 15, 1989, to June 4, 1989, in detail. Author Feng Congde is one of the student leader in the protest and his day-by- day diary entries, record every activity during the protest including the start of student protests in Peking University, the activities of major student leaders, important events, and unexposed stories about student organizations and their complex decision making.

Many women participated in the Tiananmen Square Protests of 1989 for democratic reform in China. Lee Feigon states "women [during the Tiananmen Square Protests] were relegated for the most part to traditional support roles." Chai Ling and Wang Chaohua, however, were female student leaders taking part in leadership activities during the pro-democracy movement. Ranging from student leaders to intellectuals, many women contributed their opinions and leadership skills to the movement. Although women had substantial roles, they had different standpoints regarding the hunger strike movement on May 13.

The first of two student hunger strikes during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre began on May 13, 1989, in Beijing. The students said that they were willing to risk their lives to gain the government's attention. They believed that because plans were in place for the grand welcoming of Mikhail Gorbachev, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, on May 15, at Tiananmen Square, the government would respond. Although the students gained a dialogue session with the government on May 14, no rewards materialized. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) did not heed the students' demands and moved the welcome ceremony to the airport.

The protests that occurred throughout the People's Republic of China in the early to middle months of 1989 mainly started out as memorials for former General Secretary Hu Yaobang. The political fall of Hu came immediately following the 1986 Chinese Student Demonstrations when he was removed by paramount leader Deng Xiaoping for being too liberal in his policies. Upon Hu's death on April 15, 1989, large gatherings of people began forming across the country. Most media attention was put onto the Beijing citizens who participated in the Tiananmen Square Protests, however, every other region in China had cities with similar demonstrations. The origins of these movements gradually became forgotten in some places and some regions began to demonstrate based on their own problems with their Provincial and Central Governments.

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were a turning point for many Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials, who were subjected to a purge that started after June 4, 1989. The purge covered top-level government figures down to local officials, and included CCP General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and his associates. The purge took the form of a massive ideological campaign that lasted 18 months. At least 4 million Communist Party members were under some sort of investigation. The government stated that the purge was undertaken for the purpose of “resolutely getting rid of hostile elements, antiparty elements, and corrupt elements" as well as "dealing strictly with those inside the party serious tendencies toward bourgeois liberalization” and purify the party.

Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China is a scholarly book by Rowena Xiaoqing He, published by Palgrave Macmillan in April 2014. The book has been named one of the Top five China Books by the Asia Society. It is primarily an oral history of Yi Danxuan, Shen Tong, and Wang Dan, all exiled student leaders from the 1989 Tiananmen Movement in China. "Tracing the life trajectories of these exiles, from childhood during Mao's Cultural Revolution, adolescence growing up during the reform era, and betrayal and punishment in the aftermath of June 1989, to ongoing struggles in exile", the author explores, "how their idealism was fostered by the very powers that ultimately crushed it, and how such idealism evolved facing the conflicts that historical amnesia, political commitment, ethical action, and personal happiness presented to them in exile." Dan Southerland notes in Christian Science Monitor that the book provides "fresh insights and an appreciation for the challenges that exiled Chinese student leaders faced after they escaped from China." Paul Levine from American Diplomacy states that there was “a fourth major character: the author herself.” Tiananmen Exiles is a part of the Palgrave Studies in Oral History and contains a foreword by Perry Link. The forward was published in the New York Review of Books the same week the book came out.

References

- ↑ The Tiananmen Papers, ed. Zhang Liang, Andrew J. Nathan, and Perry Link (New York: PublicAffairs, 2001), 51.

- ↑ Joint Committee on Women and Youth of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference and the Central Office of the Communist Youth League, "Report on a survey of the current state of ideology among youth," in The Tiananmen Papers, ed. Zhang Liang, Andrew J. Nathan, and Perry Link (New York: PublicAffairs, 2001), 12-13.

- ↑ Shen Tong and Marianne Yen, Almost a Revolution (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990), 223.

- ↑ Shen Tong, Almost a Revolution, 247-248.

- ↑ "Yuan Mu Others Hold Dialogue with Students [April 29, 1989]," in Beijing Spring, 1989: Confrontation and Conflict – The Basic Documents, ed. Michel Oksenberg, Lawrence R. Sullivan, and Marc Lambert (New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1990), 218.

- ↑ "Li Peng Holds Dialogue with Students," in Beijing Spring, 1989: Confrontation and Conflict – The Basic Documents, ed. Michel Oksenberg, Lawrence R. Sullivan, and Marc Lambert (New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1990), 269.

- ↑ "Yuan Mu and Others Hold Dialogue with Students [April 29, 1989]," Beijing Spring, 1989, 218.

- ↑ "Yuan Mu and Others Hold Dialogue with Students [April 29, 1989]," Beijing Spring, 1989, 224.

- ↑ Graduate Students of Beijing Normal University, "Is it a Dialogue or an Admonitory Talk? On the "Dialogue" of April 29," in China's Search for Democracy: The Student and The Mass Movement of 1989, ed. Suzanne Ogden, Kathleen Hartford, Lawrence Sullivan, and David Zweig (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1992), 149.

- ↑ Anonymous, "True Story of the So-Called Dialogue," in China's Search for Democracy: The Student and The Mass Movement of 1989, ed. Suzanne Ogden, Kathleen Hartford, Lawrence Sullivan, and David Zweig (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1992), 143.

- ↑ "Yuan Mu's Dialogue," in The Tiananmen Papers, ed. Zhang Liang, Andrew J. Nathan, and Perry Link (New York: PublicAffairs, 2001), 96.

- ↑ Shen Tong, Almost a Revolution, 229.

- ↑ Shen Tong, Almost a Revolution, 224.

- 1 2 Shen Tong, Almost a Revolution, 244.

- ↑ Shen Tong, Almost a Revolution, 246.

- ↑ Shen Tong, Almost a Revolution, 247.

- 1 2 3 4 "Li Peng holds dialogue with students". Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 19 May 1989.

- ↑ "Li Peng Holds Dialogue with Students," Beijing Spring, 1989, 269.

- ↑ Louisa Lim, The People's Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 60.

- ↑ Li, Peng (2010). The Critical Moment – Li Peng Diaries. Hong Kong: Au Ya Publishing. pp. Entry for May 18. ISBN 978-1921815003.

- ↑ "Li Peng Holds Dialogue with Students," Beijing Spring, 1989, 279.

- ↑ Anonymous, "True Story of the So-Called Dialogue," 143.

- ↑ Wudunn, Sheryl; Times, Special To the New York (1989-04-30). "China Hears Out Students, and Lets Millions Listen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ↑ "Li Peng Holds Dialogue with Students," Beijing Spring, 1989, 270.