Jamaica Kincaid is an Antiguan–American novelist, essayist, gardener, and gardening writer. Born in St. John's, the capital of Antigua and Barbuda, she now lives in North Bennington, Vermont, and is Professor of African and African American Studies in Residence, Emerita at Harvard University.

Edwidge Danticat is a Haitian-American novelist and short story writer. Her first novel, Breath, Eyes, Memory, was published in 1994 and went on to become an Oprah's Book Club selection. Danticat has since written or edited several books and has been the recipient of many awards and honors. As of the fall of 2023, she will be the Wun Tsun Tam Mellon Professor of the Humanities in the department of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself is an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs, a mother and fugitive slave, published in 1861 by L. Maria Child, who edited the book for its author. Jacobs used the pseudonym Linda Brent. The book documents Jacob's life as a slave and how she gained freedom for herself and for her children. Jacobs contributed to the genre of slave narrative by using the techniques of sentimental novels "to address race and gender issues." She explores the struggles and sexual abuse that female slaves faced as well as their efforts to practice motherhood and protect their children when their children might be sold away.

Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage is a book of short stories by Alice Munro, published by McClelland and Stewart in 2001.

Mary Gaitskill is an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper's Magazine, Esquire, The Best American Short Stories, and The O. Henry Prize Stories. Her books include the short story collection Bad Behavior (1988) and Veronica (2005), which was nominated for both the National Book Award for Fiction and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction.

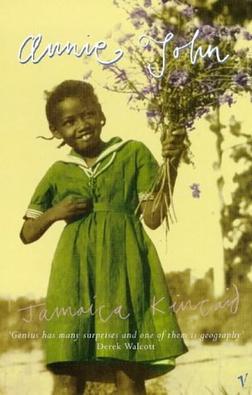

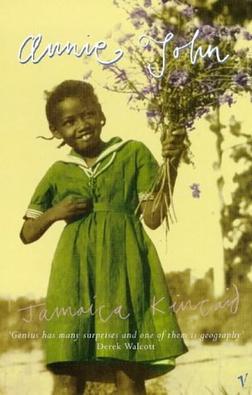

Annie John, a novel written by Jamaica Kincaid in 1985, details the growth of a girl in Antigua, an island in the Caribbean. It covers issues as diverse as mother-daughter relationships, same-sex attraction, racism, clinical depression, poverty, education, and the struggle between medicine based on "scientific fact" and that based on "native superstitious know-how".

A Small Place is a work of creative nonfiction published in 1988 by Jamaica Kincaid. A book-length essay drawing on Kincaid's experiences growing up in Antigua, it can be read as an indictment of the Antiguan government, the tourist industry and Antigua's British colonial legacy, which includes slavery.

The View from Castle Rock is a book of short stories by Canadian author Alice Munro, recipient of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature, which was published in 2006 by McClelland and Stewart.

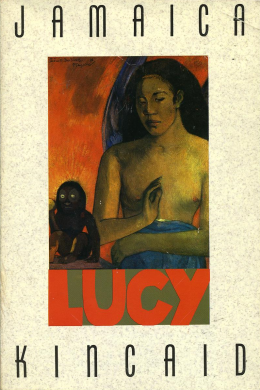

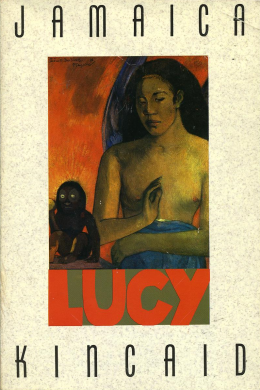

Lucy (1990) is a novella by Jamaica Kincaid. The story begins in medias res: the eponymous Lucy has come from the West Indies to the United States to be an au pair for a wealthy white family. The plot of the novel closely mirrors Kincaid's own experiences.

No Telephone to Heaven, the sequel to Abeng (novel), is the second novel published by Jamaican-American author Michelle Cliff. The novel continues the story of Clare Savage, Cliff's semi-autobiographical character from Abeng, through a set of flashbacks that recount Clare's adolescence and young adulthood as she moves from Jamaica to the United States, then to England, and finally back to Jamaica. First published in 1987, the book has received attention for its articulation of the paradoxes of history and identity after, and counter to, the experience of colonization.

Merle Hodge is a Trinidadian novelist and literary critic. Her 1970 novel Crick Crack, Monkey is a classic of West Indian literature, and Hodge is acknowledged as the first black Caribbean woman to have published a major work of fiction.

Krik? Krak! (ISBN 0-679-76657-X) is a 1996 collection of short stories by Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat. It consists of nine short stories plus an epilogue. The stories are tied together by similar plots of struggle and survival within the Haitian community. The title of the books is a reference to the Haitian cultural tradition of folk storytelling.

Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories is a book of short stories published in 1991 by the Mexican-American writer Sandra Cisneros. The collection reflects Cisneros's experience of being surrounded by American influences while still being familially bound to her Mexican heritage as she grew up north of the Mexico-US border.

Mating (1991) is a novel by American author Norman Rush. It is a first-person narrative by an unnamed American anthropology graduate student in Botswana around 1980. It focuses on her relationship with Nelson Denoon, a controversial American social scientist who has founded an experimental matriarchal village in the Kalahari desert.

Self-Help (1985) is a collection of short stories by Lorrie Moore.

"Girl" is a short story written by Jamaica Kincaid that was included in At the Bottom of the River (1983). It appeared in the June 26, 1978 issue of The New Yorker.

Margaret Cezair-Thompson is a Jamaican writer and a professor of literature and creative writing at Wellesley College.

Black Tickets (1979) is a collection of short stories by American writer Jayne Anne Phillips. The collection was published by Delacorte Books/Seymour Lawrence. In 1980, it won the inaugural Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction.

Jacqueline Bishop is a writer, visual artist and photographer from Jamaica, who now lives in New York City, where she is a professor at the School of Liberal Studies at New York University (NYU). She is the founder of Calabash, an online journal of Caribbean art and letters, housed at NYU, and also writes for the Huffington Post and the Jamaica Observer Arts Magazine. In 2016 her book The Gymnast and Other Positions won the nonfiction category of the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. She is a contributor to the 2019 anthology New Daughters of Africa, edited by Margaret Busby.

"The Echo" is a short story by Paul Bowles written in 1946 and first published in the September 1946 issue of Harper's Bazaar magazine. It was later published in a collection of his short fiction, The Delicate Prey and Other Stories, published by Random House in 1950.