Life

Born at Lenham in Kent, Quaife was the son of a farmer, Thomas Quaife, and his wife, Amelia Austin. [2] He entered the Hoxton Academy in London in 1824; later he served as a teacher and minister in Collompton, Devon, and St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex, [3] among other locations. In 1835 Quaife submitted a "Plan to provide the New Settlement of South Australia with the means of Religious instruction on the Congregational principle" to the South Australian Colonization Commissioners; he was not, however, appointed under this plan, nor was he allowed to serve when he applied again in 1836. [3] He did finally reach Adelaide in September 1839, with the assistance of George Fife Angas; here he established a Bible and tract depot and spent six months writing for Archibald Macdougall's Southern Australian. [3] before being persuaded to establish his own paper in New Zealand [2]

Quaife and his family arrived at Kororareka (today Russell) on the Agenoria in May 1840. On 15 June of that year the first issue of the New Zealand Advertiser and Bay of Islands Gazette was published. It was the second newspaper to be printed in the colony, and contained government-issued material; nevertheless, Quaife exercised an editorial policy directly contrary to, and critical of, government policy. [2] He voiced strong support for the rights of the Māori, and was displeased by poorly-performing public servants; most of his focus was on indigenous rights - especially regarding land - and criminal justice. He has been called "New Zealand's first public anti-racist"; [2] among his harshest statements on the issue was one that "when…the Governor…lays it down as an axiom…that the natives have no independent right over their own property…we see no end - looking at the Cape as an example - of the catalogue of miseries which may be entailed on this inoffensive people". [2] He further argued that the land act of August 1840, supported by governor George Gipps and allowing the governor of New South Wales to appoint commissioners to investigate land-related issues in New Zealand, was unenforceable and would lead to trouble. [2]

It has been suggested that Quaife's personality, combined with a liberal education and experience with both a free colony and an unencumbered, openly critical press, meant that he was destined for problems with authority. [2] In the event he came into conflict with the chief police magistrate and acting colonial secretary, Willoughby Shortland. Shortland was fresh from New South Wales, where the press was controlled, and in December 1840, recalling an old ordinance from that colony, he ordered Quaife to post several hundred pounds' surety and pay a fine. Should he do neither, he would face penal transportation for publishing "tending to bring the Government into hatred or contempt". [2] Consequently, the last edition of the Advertiser appeared on 10 December. Undeterred, Quaife returned to publishing in 1842, launching the Bay of Islands Observer. His platform was much the same as before. Foolishly, however, he printed some gossip about George Cooper, a former colonial treasurer. He apologized publicly, but was still dismissed by the paper's owners. From that time forward he devoted himself to the Kororareka Congregational Church, which he had founded as New Zealand's first Congregational church in 1840. He also taught and ran a bookshop. [2]

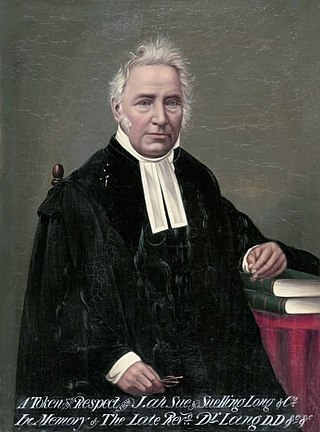

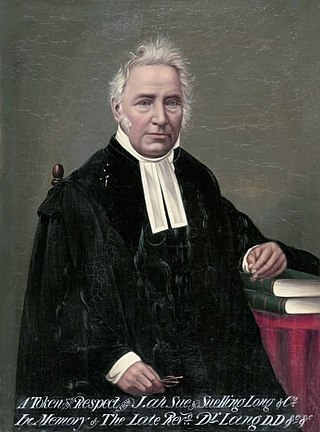

May 1844 found Quaife financially exhausted and intending to return to England. [2] He left for Sydney, intending to spend a short time there, and began preaching in Parramatta, where he stayed to form a Congregational church and build a chapel. He knew the Rev. Dr. Robert Ross of the Pitt Street Congregational Church, but their relationship was never a very easy one, and all connections between them were severed when Quaife was offered a temporary appointment to replace John Dunmore Lang at the Scots Church while the latter was away. [3] He then continued as pastor at the Parramatta church until its closure in 1850; meanwhile, he kept up his service at the Scots Church until February 1847, when it received a Presbyterian minister. Some of the congregation wished to retain Quaife's services, and chose to leave their church and found a new one under him. This organization first met in the Wesleyan Chapel on Macquarie Street before moving to the old City Theatre in Market Street. [3] At the Scots Church he lectured on the evils of Catholicism. [4]

Quaife ministered to this group until 1850, in which year Dr. Lang reopened the Australian College and appointed him to the faculty as a professor of mental philosophy and divinity. He became a foundation member of two synods, that of New South Wales in 1850 and of the reunited ones in 1865. The college's work was restricted in 1852, at which point his teaching position lapsed. He lived again in Parramatta between 1853 and 1855. In the latter year Quaife went to Paddington teaching school while ministering to a congregation at home. 1863 saw reconciliation with Congregational leaders, from whom he had become estranged, and he was invited to train three of their students for the ministry. He closed his school and brought his congregation into the Ocean Street Congregational Church in Woollahra. He tutored his three students until September 1864; in October they were transferred to the then-new Camden College. Quaife did not receive a teaching position at the school, which omission hurt him deeply. Ill health at this point forced him to withdraw from professional work until his death. [3]

Quaife died in Woollahra in 1873. [2]

Thomas Spencer Forsaith, JP, was a New Zealand politician and an Auckland draper. According to some historians, he was the country's second premier, although a more conventional view states that neither he nor his predecessor should properly be given that title.

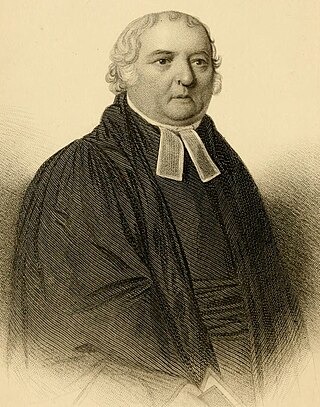

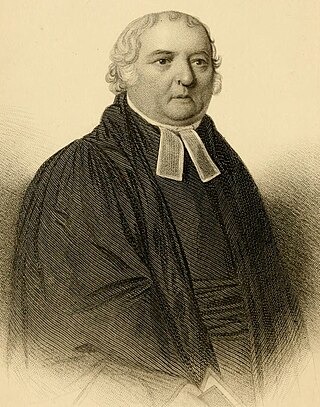

John Dunmore Lang was a Scottish-born Australian Presbyterian minister, writer, historian, politician and activist. He was the first prominent advocate of an independent Australian nation and of Australian republicanism.

Samuel Marsden was an English-born priest of the Church of England in Australia and a prominent member of the Church Missionary Society. He played a leading role in bringing Christianity to New Zealand. Marsden was a prominent figure in early New South Wales and Australian history, partly through his ecclesiastical offices as the colony's senior Church of England cleric and as a pioneer of the Australian wool industry, but also for his employment of convicts for farming and his actions as a magistrate at Parramatta, both of which attracted contemporary criticism.

Commander Willoughby Shortland RN was a British naval officer and colonial administrator. He was New Zealand's first Colonial Secretary from 1841, after having arrived in New Zealand with Lieutenant Governor William Hobson in January 1840. He was later President of the island of Nevis and then Governor of Tobago.

Joel Samuel Polack was an English-born New Zealand and American businessman and writer. He was one of the first Jewish settlers in New Zealand, arriving in 1831. He is regarded as an authority on pre-colonial New Zealand and his two books are often cited. He was a maternal uncle of Alexander Salmon.

James Forbes was a Scottish-Australian Presbyterian minister and educator. He founded the Melbourne Academy, later Scotch College.

Thomas Binney (1798–1874) was an English Congregationalist divine of the 19th century, popularly known as the "Archbishop of Nonconformity". He was noted for sermons and writings in defence of the principles of Nonconformity, for devotional verse, and for involvement in the cause of anti-slavery.

Elizabeth Macarthur was an Anglo-Australian pastoralist and merchant, and wife of John Macarthur.

Joseph Coles Kirby was an English flour miller who migrated to Sydney, Australia in 1854. In 1864, Kirby was ordained in the Congregational Churches and then ministered to rural and city congregations in Queensland and South Australia and supported or led many causes for social reform such as the temperance movement, women's suffrage and raising the age of consent to 16 in Australia.

Sir Charles Lloyd Jones was an Australian businessman and patron of the arts, serving as Chairman of David Jones Limited from 1920 to his death in 1958.

The Rev. John West emigrated from England to Van Diemen's Land in 1838 as a Colonial missionary, and became pastor of an Independent (Congregational) Chapel in Launceston's St. John's Square. He also co-founded The Examiner newspaper in 1842 and was later editor of The Sydney Morning Herald.

The Reverend Arthur "Ashworth" Aspinall was a co-founder and the first Principal of The Scots College, Bellevue Hill, Sydney, Australia. He was a Congregational and Presbyterian Minister, and a joint founder of the Historical Society of New South Wales. A portrait of Arthur Aspinall is found in Cameron's Centenary History, p. 320, Plate 99.

Reader Gillson Wood was a 19th-century New Zealand politician. An architect by trade, he designed the 1854 General Assembly House built as New Zealand's first meeting house for the House of Representatives.

1840 is considered a watershed year in the history of New Zealand: The Treaty of Waitangi is signed, British sovereignty over New Zealand is proclaimed, organised European settlement begins, and Auckland and Wellington are both founded.

The Octagon, Christchurch, the former Trinity Church or Trinity Congregational Church designed by Benjamin Mountfort, later called the State Trinity Centre, is a Category I heritage building listed with Heritage New Zealand. Damaged in the 2010 Canterbury earthquake and red-stickered after the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake, the building was threatened with demolition like most other central city heritage buildings. In June 2012, it was announced that the building will be saved, repaired and earthquake strengthened.

The first Congregational Church in New Zealand was formed in 1840 by Rev. Barzillai Quaife, who was a missionary to the Maori. This cause did not give rise to any lasting church, neither did one formed in New Plymouth in February 1842. Mr. Jonas Woodward, a leading businessman in Wellington, founded the Congregational church in Wellington in May 1842, and because this gave rise to a long term church, it is considered by all as the first. There was considerable growth in both North and South Islands with churches established in Auckland in 1851, Dunedin in 1862 and Christchurch in 1864 and many other places also. The 1875 Census lists the Congregational Independents as the fourth largest Protestant Denomination in Auckland, and the fifth largest in 'The Colony.' Initially because of lack of roads, two unions were formed, one in the North Island the other mainly in the South Island. These merged to form the Congregational Union of New Zealand (CUNZ) in 1884. In 1890s women were admitted to the Assembly as full members. In 1902 the Presbyterian church made overtures to the CUNZ and the Methodist Churches regarding church union. Discussions on this were held occasionally over many years but no real action was taken. However, in 1943 the Raglan Congregational church merged with the Presbyterian church to form the first Union church in New Zealand. In 2019 this church severed all ties with the Presbyterian and Methodist churches and became a Congregational church again. A few months later the Assembly of the CUNZ severed all ties with the Uniting Churches of Aotearoa New Zealand (UCANZ), as the body was now called.

Scots Church is a stone Uniting Church building on the southwest corner of North Terrace and Pulteney Street in Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia. It was one of the early churches built in the new city in 1850. It was built as the "Chalmers Free Church of Scotland".

The Scots Church is a historic Presbyterian church located at 42–44 Margaret Street on the corner of York Street, in the Sydney central business district, in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by Rosenthal, Rutledge & Beattie and built by Beat Bros in 1929. Since 2005, the 1929 building has supported a high rise apartment building on top of it, designed by Tonkin Zulaikha Greer.

Samuel Leigh was a prominent minister and missionary for the Wesleyan Methodist Church in early colonial New South Wales and New Zealand.

The New Zealand Advertiser and Bay of Islands Gazette was New Zealand's second newspaper and the original publication used by the colonial administration to publish official notices. The newspaper was published in Kororāreka from June to December 1840.