A calorimeter is a device used for calorimetry, or the process of measuring the heat of chemical reactions or physical changes as well as heat capacity. Differential scanning calorimeters, isothermal micro calorimeters, titration calorimeters and accelerated rate calorimeters are among the most common types. A simple calorimeter just consists of a thermometer attached to a metal container full of water suspended above a combustion chamber. It is one of the measurement devices used in the study of thermodynamics, chemistry, and biochemistry.

A heat exchanger is a system used to transfer heat between a source and a working fluid. Heat exchangers are used in both cooling and heating processes. The fluids may be separated by a solid wall to prevent mixing or they may be in direct contact. They are widely used in space heating, refrigeration, air conditioning, power stations, chemical plants, petrochemical plants, petroleum refineries, natural-gas processing, and sewage treatment. The classic example of a heat exchanger is found in an internal combustion engine in which a circulating fluid known as engine coolant flows through radiator coils and air flows past the coils, which cools the coolant and heats the incoming air. Another example is the heat sink, which is a passive heat exchanger that transfers the heat generated by an electronic or a mechanical device to a fluid medium, often air or a liquid coolant.

In industrial process engineering, mixing is a unit operation that involves manipulation of a heterogeneous physical system with the intent to make it more homogeneous. Familiar examples include pumping of the water in a swimming pool to homogenize the water temperature, and the stirring of pancake batter to eliminate lumps (deagglomeration).

A microreactor or microstructured reactor or microchannel reactor is a device in which chemical reactions take place in a confinement with typical lateral dimensions below 1 mm; the most typical form of such confinement are microchannels. Microreactors are studied in the field of micro process engineering, together with other devices in which physical processes occur. The microreactor is usually a continuous flow reactor. Microreactors can offer many advantages over conventional scale reactors, including improvements in energy efficiency, reaction speed and yield, safety, reliability, scalability, on-site/on-demand production, and a much finer degree of process control.

A bioreactor is any manufactured device or system that supports a biologically active environment. In one case, a bioreactor is a vessel in which a chemical process is carried out which involves organisms or biochemically active substances derived from such organisms. This process can either be aerobic or anaerobic. These bioreactors are commonly cylindrical, ranging in size from litres to cubic metres, and are often made of stainless steel. It may also refer to a device or system designed to grow cells or tissues in the context of cell culture. These devices are being developed for use in tissue engineering or biochemical/bioprocess engineering.

A chemical reactor is an enclosed volume in which a chemical reaction takes place. In chemical engineering, it is generally understood to be a process vessel used to carry out a chemical reaction, which is one of the classic unit operations in chemical process analysis. The design of a chemical reactor deals with multiple aspects of chemical engineering. Chemical engineers design reactors to maximize net present value for the given reaction. Designers ensure that the reaction proceeds with the highest efficiency towards the desired output product, producing the highest yield of product while requiring the least amount of money to purchase and operate. Normal operating expenses include energy input, energy removal, raw material costs, labor, etc. Energy changes can come in the form of heating or cooling, pumping to increase pressure, frictional pressure loss or agitation.

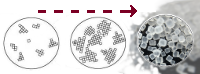

Crystallization is the process by which solids form, where the atoms or molecules are highly organized into a structure known as a crystal. Some ways by which crystals form are precipitating from a solution, freezing, or more rarely deposition directly from a gas. Attributes of the resulting crystal depend largely on factors such as temperature, air pressure, cooling rate, and in the case of liquid crystals, time of fluid evaporation.

Continuous production is a flow production method used to manufacture, produce, or process materials without interruption. Continuous production is called a continuous process or a continuous flow process because the materials, either dry bulk or fluids that are being processed are continuously in motion, undergoing chemical reactions or subject to mechanical or heat treatment. Continuous processing is contrasted with batch production.

A chemical plant is an industrial process plant that manufactures chemicals, usually on a large scale. The general objective of a chemical plant is to create new material wealth via the chemical or biological transformation and or separation of materials. Chemical plants use specialized equipment, units, and technology in the manufacturing process. Other kinds of plants, such as polymer, pharmaceutical, food, and some beverage production facilities, power plants, oil refineries or other refineries, natural gas processing and biochemical plants, water and wastewater treatment, and pollution control equipment use many technologies that have similarities to chemical plant technology such as fluid systems and chemical reactor systems. Some would consider an oil refinery or a pharmaceutical or polymer manufacturer to be effectively a chemical plant.

A coolant is a substance, typically liquid, that is used to reduce or regulate the temperature of a system. An ideal coolant has high thermal capacity, low viscosity, is low-cost, non-toxic, chemically inert and neither causes nor promotes corrosion of the cooling system. Some applications also require the coolant to be an electrical insulator.

In flow chemistry, also called reactor engineering, a chemical reaction is run in a continuously flowing stream rather than in batch production. In other words, pumps move fluid into a reactor, and where tubes join one another, the fluids contact one another. If these fluids are reactive, a reaction takes place. Flow chemistry is a well-established technique for use at a large scale when manufacturing large quantities of a given material. However, the term has only been coined recently for its application on a laboratory scale by chemists and describes small pilot plants, and lab-scale continuous plants. Often, microreactors are used.

A reaction calorimeter is a calorimeter that measures the amount of energy released or absorbed by a chemical reaction. It does this by measuring the total change in temperature of an exact amount of water in a vessel.

A fluidized bed reactor (FBR) is a type of reactor device that can be used to carry out a variety of multiphase chemical reactions. In this type of reactor, a fluid is passed through a solid granular material at high enough speeds to suspend the solid and cause it to behave as though it were a fluid. This process, known as fluidization, imparts many important advantages to an FBR. As a result, FBRs are used for many industrial applications.

In systems involving heat transfer, a condenser is a heat exchanger used to condense a gaseous substance into a liquid state through cooling. In doing so, the latent heat is released by the substance and transferred to the surrounding environment. Condensers are used for efficient heat rejection in many industrial systems. Condensers can be made according to numerous designs and come in many sizes ranging from rather small (hand-held) to very large. For example, a refrigerator uses a condenser to get rid of heat extracted from the interior of the unit to the outside air.

Continuous reactors carry material as a flowing stream. Reactants are continuously fed into the reactor and emerge as continuous stream of product. Continuous reactors are used for a wide variety of chemical and biological processes within the food, chemical and pharmaceutical industries. A survey of the continuous reactor market will throw up a daunting variety of shapes and types of machine. Beneath this variation however lies a relatively small number of key design features which determine the capabilities of the reactor. When classifying continuous reactors, it can be more helpful to look at these design features rather than the whole system.

In chemical engineering, a jacketed vessel is a container that is designed for controlling temperature of its contents, by using a cooling or heating "jacket" around the vessel through which a cooling or heating fluid is circulated.

Industrial agitators are machines used to stir or mix fluids in industries that process products in the chemical, food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries. Their uses include:

In fluid thermodynamics, a heat transfer fluid is a gas or liquid that takes part in heat transfer by serving as an intermediary in cooling on one side of a process, transporting and storing thermal energy, and heating on another side of a process. Heat transfer fluids are used in countless applications and industrial processes requiring heating or cooling, typically in a closed circuit and in continuous cycles. Cooling water, for instance, cools an engine, while heating water in a hydronic heating system heats the radiator in a room.

The circulating fluidized bed (CFB) is a type of fluidized bed combustion that utilizes a recirculating loop for even greater efficiency of combustion. while achieving lower emission of pollutants. Reports suggest that up to 95% of pollutants can be absorbed before being emitted into the atmosphere. The technology is limited in scale however, due to its extensive use of limestone, and the fact that it produces waste byproducts.

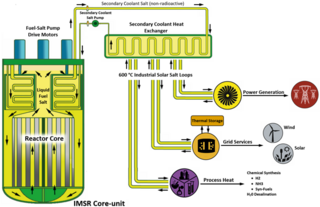

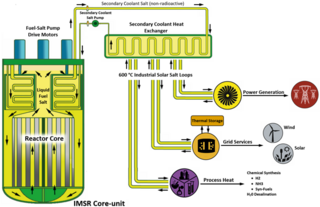

The integral molten salt reactor (IMSR) is a nuclear power plant design targeted at developing a commercial product for the small modular reactor (SMR) market. It employs molten salt reactor technology which is being developed by the Canadian company Terrestrial Energy.