Carthage was an ancient city on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classical world. It became the capital city of the civilisation of Ancient Carthage and later Roman Carthage.

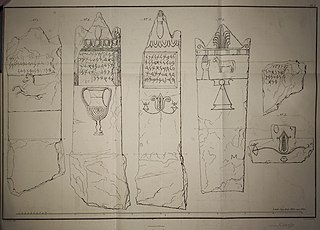

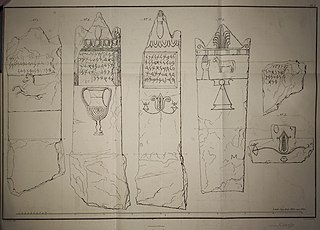

An epitaph is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves before their death, while others are chosen by those responsible for the burial. An epitaph may be written in prose or in poem verse.

The Punic language, also called Phoenicio-Punic or Carthaginian, is an extinct variety of the Phoenician language, a Canaanite language of the Northwest Semitic branch of the Semitic languages. An offshoot of the Phoenician language of coastal West Asia, it was principally spoken on the Mediterranean coast of Northwest Africa, the Iberian peninsula and several Mediterranean islands, such as Malta, Sicily, and Sardinia by the Punic people, or western Phoenicians, throughout classical antiquity, from the 8th century BC to the 6th century AD.

A nefesh is a Semitic monument placed near a grave so as to be seen from afar.

Dougga or Thugga or TBGG was a Berber, Punic and Roman settlement near present-day Téboursouk in northern Tunisia. The current archaeological site covers 65 hectares. UNESCO qualified Dougga as a World Heritage Site in 1997, believing that it represents "the best-preserved Roman small town in North Africa". The site, which lies in the middle of the countryside, has been protected from the encroachment of modern urbanization, in contrast, for example, to Carthage, which has been pillaged and rebuilt on numerous occasions. Dougga's size, its well-preserved monuments and its rich Numidian-Berber, Punic, ancient Roman, and Byzantine history make it exceptional. Amongst the most famous monuments at the site are a Libyco-Punic Mausoleum, the Capitol, the Roman theatre, and the temples of Saturn and of Juno Caelestis.

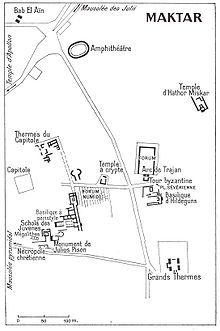

Maktar or Makthar, also known by other names during antiquity, is a town and archaeological site in Siliana Governorate, Tunisia.

The Punic religion, Carthaginian religion, or Western Phoenician religion in the western Mediterranean was a direct continuation of the Phoenician variety of the polytheistic ancient Canaanite religion. However, significant local differences developed over the centuries following the foundation of Carthage and other Punic communities elsewhere in North Africa, southern Spain, Sardinia, western Sicily, and Malta from the ninth century BC onward. After the conquest of these regions by the Roman Republic in the third and second centuries BC, Punic religious practices continued, surviving until the fourth century AD in some cases. As with most cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, Punic religion suffused their society and there was no stark distinction between religious and secular spheres. Sources on Punic religion are poor. There are no surviving literary sources and Punic religion is primarily reconstructed from inscriptions and archaeological evidence. An important sacred space in Punic religion appears to have been the large open air sanctuaries known as tophets in modern scholarship, in which urns containing the cremated bones of infants and animals were buried. There is a long-running scholarly debate about whether child sacrifice occurred at these locations, as suggested by Greco-Roman and biblical sources.

The Lapis Niger is an ancient shrine in the Roman Forum. Together with the associated Vulcanal it constitutes the only surviving remnants of the old Comitium, an early assembly area that preceded the Forum and is thought to derive from an archaic cult site of the 7th or 8th century BC.

Ancient Carthage was an ancient Semitic civilisation based in North Africa. Initially a settlement in present-day Tunisia, it later became a city-state and then an empire. Founded by the Phoenicians in the ninth century BC, Carthage reached its height in the fourth century BC as one of the largest metropoleis in the world. It was the centre of the Carthaginian Empire, a major power led by the Punic people who dominated the ancient western and central Mediterranean Sea. Following the Punic Wars, Carthage was destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC, who later rebuilt the city lavishly.

Carthage National Museum is a national museum in Byrsa, Tunisia. Along with the Bardo National Museum, it is one of the two main local archaeological museums in the region. The edifice sits atop Byrsa Hill, in the heart of the city of Carthage. Founded in 1875, it houses many archaeological items from the Punic era and other periods.

The Cippi of Melqart are a pair of Phoenician marble cippi that were unearthed in Malta under undocumented circumstances and dated to the 2nd century BC. These are votive offerings to the god Melqart, and are inscribed in two languages, Ancient Greek and Phoenician, and in the two corresponding scripts, the Greek and the Phoenician alphabet. They were discovered in the late 17th century, and the identification of their inscription in a letter dated 1694 made them the first Phoenician writing to be identified and published in modern times. Because they present essentially the same text, the cippi provided the key to the modern understanding of the Phoenician language. In 1758, the French scholar Jean-Jacques Barthélémy relied on their inscription, which used 17 of the 22 letters of the Phoenician alphabet, to decipher the unknown language.

The funerary art of ancient Rome changed throughout the course of the Roman Republic and the Empire and took many different forms. There were two main burial practices used by the Romans throughout history, one being cremation, another inhumation. The vessels used for these practices include sarcophagi, ash chests, urns, and altars. In addition to these, mausoleums, stele, and other monuments were also used to commemorate the dead. The method by which Romans were memorialized was determined by social class, religion, and other factors. While monuments to the dead were constructed within Roman cities, the remains themselves were interred outside the cities.

The Libyco-Punic Mausoleum of Dougga is an ancient mausoleum located in Dougga, Tunisia. It is one of three examples of the royal architecture of Numidia, which is in a good state of preservation and dates to the second century BC. It was restored by the government of French Tunisia between 1908 and 1910.

Carthaginian tombstones are Punic language-inscribed tombstones excavated from the city of Carthage over the last 200 years. The first such discoveries were published by Jean Emile Humbert in 1817, Hendrik Arent Hamaker in 1828 and Christian Tuxen Falbe in 1833.

The National Museum of Utica is a museum dedicated to archeology in Tunisia located in Utica. The museum is dedicated to preserving important historical objects from the history of North African civilizations.

The Tomb of the Haterii is an Ancient Roman funerary monument, constructed between c. 100 and c. 120 CE along the Via Labicana to the south-east of Rome. It was discovered in 1848 and is particularly noted for the numerous artworks, particularly reliefs, found within.

The mausoleum of Lanuéjols is a Gallo-Roman funerary monument located in the commune of Lanuéjols, in the French department of Lozère.

The Asterius chapel is a small underground Christian building dating from the 5th-7th centuries, now located within the archaeological park of the Baths of Antoninus in the archaeological site of Carthage, Tunisia.

The Makthar Museum is a small Tunisian museum, inaugurated in 1967, located on the Makthar archaeological site, the ancient Mactaris. Initially a simple site museum using a building constructed to serve as a café on the site of a marabout, it comprises three rooms, some of which are displayed outside in a lapidary garden. Additionally, just behind the museum are the remains of a basilica.

The Makthar Archaeological Site, the remains of ancient Mactaris, is an archaeological site in west-central Tunisia, located in Makthar, a town on the northern edge of the Tunisian Ridge.