Dallas is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County with portions extending into Collin, Denton, Kaufman, and Rockwall counties. With a 2020 census population of 1,304,379, it is the ninth most populous city in the U.S. and the third largest city in Texas after Houston and San Antonio. Located in the North Texas region, the city of Dallas is the main core of the largest metropolitan area in the Southern United States and the largest inland metropolitan area in the U.S. that lacks any navigable link to the sea.

Arlington is a city in the U.S. state of Texas, located in Tarrant County. It forms part of the Mid-Cities region of the Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington metropolitan statistical area, and is a principal city of the metropolis and region. The city had a population of 394,266 in 2020, making it the second-largest city in the county, after Fort Worth, and the third-largest city in the metropolitan area, after Dallas and Fort Worth. Arlington is the 50th-most populous city in the United States, the seventh-most populous city in the state of Texas, and the largest city in the state that is not a county seat.

Arlington Stadium was a baseball stadium located in Arlington, Texas, United States, located between Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas. It served as the home for the Texas Rangers (MLB) from 1972 until 1993, after which the team moved into The Ballpark in Arlington.

This article traces the history of Dallas, Texas,.

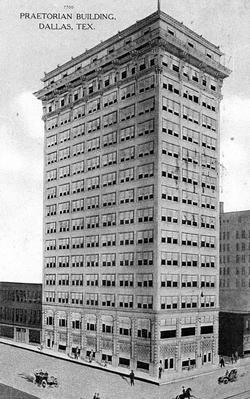

The history of Dallas, Texas, United States from 1874 to 1929 documents the city's rapid growth and emergence as a major center for transportation, trade and finance. Originally a small community built around agriculture, the convergence of several railroads made the city a strategic location for several expanding industries. During the time, Dallas prospered and grew to become the most populous city in Texas, lavish steel and masonry structures replaced timber constructions, Dallas Zoo, Southern Methodist University, and an airport were established. Conversely, the city suffered multiple setbacks with a recession from a series of failing markets and the disastrous flooding of the Trinity River in the spring of 1908.

The Swiss Avenue Historic District is a residential neighborhood in East Dallas, Dallas, Texas (USA). It consists of installations of the Munger Place addition, one of East Dallas' early subdivisions. The Swiss Avenue Historic District is a historic district of the city of Dallas, Texas. The boundaries of the district comprise both sides of Swiss Avenue from Fitzhugh Street, to just north of La Vista, and includes portions of Bryan Parkway. The District includes the 6100-6200 blocks of La Vista Drive, the west side of the 5500 block of Bryan Parkway the 6100-6300 blocks of Bryan Parkway, the east side of the 5200-5300 block of Live Oak Street, and the 4900-6100 blocks of Swiss Avenue. The entire street of Swiss Avenue is not included within the bounds of the Swiss Avenue Historic District. Portions of the street run through Dallas' Peaks Suburban Addition neighborhood and Peak's Suburban Addition Historic District.

Dallas is located in North Texas, built along the Trinity River. It has a humid subtropical climate that is characteristic of the southern plains of the United States. Dallas experiences mild winters and hot summers.

Sarah Horton Cockrell was a Texan business woman who is known for her contributions to the economic and infrastructural development of the town of Dallas from 1858 to her death. At the time of her death, she is reported to have owned approximately a quarter of what was then Downtown Dallas and is said to have been one of the first millionaires in Texas.

There is a rapidly growing Mexican-American population in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 7,637,387 people in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. The racial makeup of the MSA was 50.2% White, 15.4% African American, 0.6% Native American, 5.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 10.0% from other races, and 2.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 27.5% of the population.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Arlington, Texas, USA.

Margaret Bell Houston was an American writer and suffragist who lived in Texas and New York. Houston published over 20 novels, most of them set in Texas. Her work was also published in Good Housekeeping and McCalls in serial format.

The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) was an organization formed in Dallas, Texas in 1913 to support the cause of women's suffrage in Texas. DESA was different from many other suffrage organizations in the United States in that it adopted a campaign which matched the social expectations of Dallas at the time. Members of DESA were very aware of the risk of having women's suffrage "dismissed as 'unladylike' and generally disreputable." DESA "took care to project an appropriate public image." Many members used their status as mothers in order to tie together the ideas of motherhood and suffrage in the minds of voters. The second president of DESA, Erwin Armstrong, also affirmed that women were not trying to be unfeminine, stating at an address at a 1914 Suffrage convention that "women are in no way trying to usurp the powers of men, or by any means striving to wrench from man the divine right to rule." The organization also helped smaller, nearby towns to create their own suffrage campaigns. DESA was primarily committed to securing the vote for white women, deliberately ignoring African American women in the process. Their defense of ignoring black voters was justified by having a policy of working towards "only one social reform at a time."

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Garland, Texas, United States.

Oakwood Cemetery is a historic cemetery in the city of Fort Worth, Texas. Deeded to the city in 1879, it is the burial place of local prominent local citizens, pioneers, politicians, and performers.

From 1917 to 1965, what is now the University of Texas at Arlington was a member of the Texas A&M University System. In March 1917, it was organized as Grubbs Vocational College (GVC), a junior college that was a branch campus of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (AMC), which later became Texas A&M University. Open only to white students, the curriculum at GVC centered around the agricultural, industrial, and mechanical trades.

Women's suffrage in Texas was a long term fight starting in 1868 at the first Texas Constitutional Convention. In both Constitutional Conventions and subsequent legislative sessions, efforts to provide women the right to vote were introduced, only to be defeated. Early Texas suffragists such as Martha Goodwin Tunstall and Mariana Thompson Folsom worked with national suffrage groups in the 1870s and 1880s. It wasn't until 1893 and the creation of the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) by Rebecca Henry Hayes of Galveston that Texas had a statewide women's suffrage organization. Members of TERA lobbied politicians and political party conventions on women's suffrage. Due to an eventual lack of interest and funding, TERA was inactive by 1898. In 1903, women's suffrage organizing was revived by Annette Finnigan and her sisters. These women created the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in Houston in 1903. TESA sponsored women's suffrage speakers and testified on women's suffrage in front of the Texas Legislature. In 1908 and 1912, speaking tours by Anna Howard Shaw helped further renew interest in women's suffrage in Texas. TESA grew in size and suffragists organized more public events, including Suffrage Day at the Texas State Fair. By 1915, more and more women in Texas were supporting women's suffrage. The Texas Federation of Women's Clubs officially supported women's suffrage in 1915. Also that year, anti-suffrage opponents started to speak out against women's suffrage and in 1916, organized the Texas Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (TAOWS). TESA, under the political leadership of Minnie Fisher Cunningham and with the support of Governor William P. Hobby, suffragists began to make further gains in achieving their goals. In 1918, women achieved the right to vote in Texas primary elections. During the registration drive, 386,000 Texas women signed up during a 17-day period. An attempt to modify the Texas Constitution by voter referendum failed in May 1919, but in June 1919, the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment. Texas became the ninth state and the first Southern state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on June 28, 1919. This allowed white women to vote, but African American women still had trouble voting, with many turned away, depending on their communities. In 1923, Texas created white primaries, excluding all Black people from voting in the primary elections. The white primaries were overturned in 1944 and in 1964, Texas's poll tax was abolished. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed, promising that all people in Texas had the right to vote, regardless of race or gender.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Texas. Women's suffrage was brought up in Texas at the first state constitutional convention, which began in 1868. However, there was a lack of support for the proposal at the time to enfranchise women. Women continued to fight for the right to vote in the state. In 1918, women gained the right to vote in Texas primary elections. The Texas legislature ratified the 19th amendment on June 28, 1919, becoming the ninth state and the first Southern state to ratify the amendment. While white women had secured the vote, Black women still struggled to vote in Texas. In 1944, white primaries were declared unconstitutional. Poll taxes were outlawed in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, fully enfranchising Black women voters.

Julia Cobb Crowell, known socially as Mrs. Benedict Crowell, was a clubwoman in Cleveland, Ohio, and an early leader of Girl Scouting in the United States. She was married to military officer and politician Benedict Crowell.