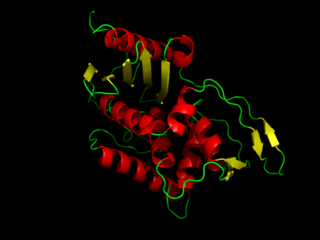

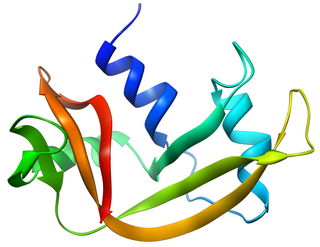

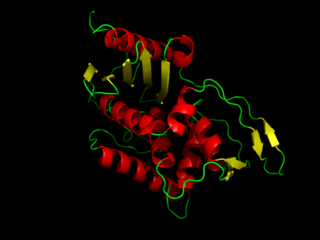

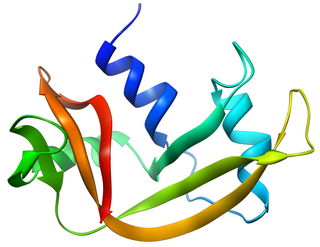

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues earlier along the protein sequence.

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a generally twisted, pleated sheet. A β-strand is a stretch of polypeptide chain typically 3 to 10 amino acids long with backbone in an extended conformation. The supramolecular association of β-sheets has been implicated in the formation of the fibrils and protein aggregates observed in amyloidosis, notably Alzheimer's disease.

Protein secondary structure is the local spatial conformation of the polypeptide backbone excluding the side chains. The two most common secondary structural elements are alpha helices and beta sheets, though beta turns and omega loops occur as well. Secondary structure elements typically spontaneously form as an intermediate before the protein folds into its three dimensional tertiary structure.

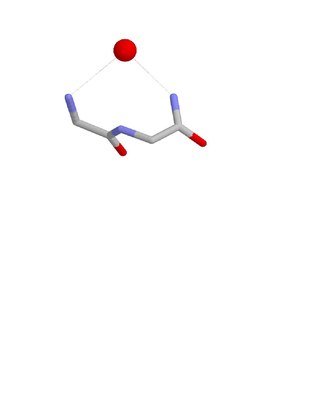

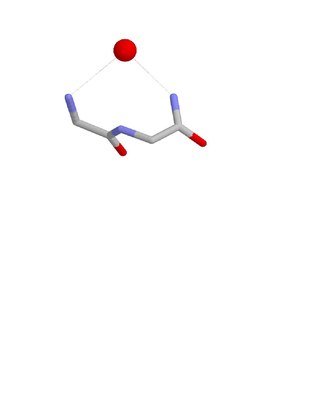

Proline (symbol Pro or P) is an organic acid classed as a proteinogenic amino acid (used in the biosynthesis of proteins), although it does not contain the amino group -NH

2 but is rather a secondary amine. The secondary amine nitrogen is in the protonated form (NH2+) under biological conditions, while the carboxyl group is in the deprotonated −COO− form. The "side chain" from the α carbon connects to the nitrogen forming a pyrrolidine loop, classifying it as a aliphatic amino acid. It is non-essential in humans, meaning the body can synthesize it from the non-essential amino acid L-glutamate. It is encoded by all the codons starting with CC (CCU, CCC, CCA, and CCG).

Alanine (symbol Ala or A), or α-alanine, is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an amine group and a carboxylic acid group, both attached to the central carbon atom which also carries a methyl group side chain. Consequently, its IUPAC systematic name is 2-aminopropanoic acid, and it is classified as a nonpolar, aliphatic α-amino acid. Under biological conditions, it exists in its zwitterionic form with its amine group protonated (as −NH3+) and its carboxyl group deprotonated (as −CO2−). It is non-essential to humans as it can be synthesised metabolically and does not need to be present in the diet. It is encoded by all codons starting with GC (GCU, GCC, GCA, and GCG).

Dehydroalanine is a dehydroamino acid. It does not exist in its free form, but it occurs naturally as a residue found in peptides of microbial origin. As an amino acid residue, it is unusual because it has an unsaturated backbone.

DD-transpeptidase is a bacterial enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of the R-L-aca-D-alanyl moiety of R-L-aca-D-alanyl-D-alanine carbonyl donors to the γ-OH of their active-site serine and from this to a final acceptor. It is involved in bacterial cell wall biosynthesis, namely, the transpeptidation that crosslinks the peptide side chains of peptidoglycan strands.

In chemistry, a foldamer is a discrete chain molecule (oligomer) that folds into a conformationally ordered state in solution. They are artificial molecules that mimic the ability of proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides to fold into well-defined conformations, such as α-helices and β-sheets. The structure of a foldamer is stabilized by noncovalent interactions between nonadjacent monomers. Foldamers are studied with the main goal of designing large molecules with predictable structures. The study of foldamers is related to the themes of molecular self-assembly, molecular recognition, and host–guest chemistry.

In organic chemistry, the Arndt–Eistert reaction is the conversion of a carboxylic acid to its homologue. Named for the German chemists Fritz Arndt (1885–1969) and Bernd Eistert (1902–1978), the method entails treating an acid chlorides with diazomethane. It is a popular method of producing β-amino acids from α-amino acids.

The Wolff rearrangement is a reaction in organic chemistry in which an α-diazocarbonyl compound is converted into a ketene by loss of dinitrogen with accompanying 1,2-rearrangement. The Wolff rearrangement yields a ketene as an intermediate product, which can undergo nucleophilic attack with weakly acidic nucleophiles such as water, alcohols, and amines, to generate carboxylic acid derivatives or undergo [2+2] cycloaddition reactions to form four-membered rings. The mechanism of the Wolff rearrangement has been the subject of debate since its first use. No single mechanism sufficiently describes the reaction, and there are often competing concerted and carbene-mediated pathways; for simplicity, only the textbook, concerted mechanism is shown below. The reaction was discovered by Ludwig Wolff in 1902. The Wolff rearrangement has great synthetic utility due to the accessibility of α-diazocarbonyl compounds, variety of reactions from the ketene intermediate, and stereochemical retention of the migrating group. However, the Wolff rearrangement has limitations due to the highly reactive nature of α-diazocarbonyl compounds, which can undergo a variety of competing reactions.

Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease, also often referred to as bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A or simply RNase A, is a pancreatic ribonuclease enzyme that cleaves single-stranded RNA. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease is one of the classic model systems of protein science. Two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry have been awarded in recognition of work on bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: in 1972, the Prize was awarded to Christian Anfinsen for his work on protein folding and to Stanford Moore and William Stein for their work on the relationship between the protein's structure and its chemical mechanism; in 1984, the Prize was awarded to Robert Bruce Merrifield for development of chemical synthesis of proteins.

A 310 helix is a type of secondary structure found in proteins and polypeptides. Of the numerous protein secondary structures present, the 310-helix is the fourth most common type observed; following α-helices, β-sheets and reverse turns. 310-helices constitute nearly 10–15% of all helices in protein secondary structures, and are typically observed as extensions of α-helices found at either their N- or C- termini. Because of the α-helices tendency to consistently fold and unfold, it has been proposed that the 310-helix serves as an intermediary conformation of sorts, and provides insight into the initiation of α-helix folding.

The beta hairpin is a simple protein structural motif involving two beta strands that look like a hairpin. The motif consists of two strands that are adjacent in primary structure, oriented in an antiparallel direction, and linked by a short loop of two to five amino acids. Beta hairpins can occur in isolation or as part of a series of hydrogen bonded strands that collectively comprise a beta sheet.

Alpha sheet is an atypical secondary structure in proteins, first proposed by Linus Pauling and Robert Corey in 1951. The hydrogen bonding pattern in an alpha sheet is similar to that of a beta sheet, but the orientation of the carbonyl and amino groups in the peptide bond units is distinctive; in a single strand, all the carbonyl groups are oriented in the same direction on one side of the pleat, and all the amino groups are oriented in the same direction on the opposite side of the sheet. Thus the alpha sheet accumulates an inherent separation of electrostatic charge, with one edge of the sheet exposing negatively charged carbonyl groups and the opposite edge exposing positively charged amino groups. Unlike the alpha helix and beta sheet, the alpha sheet configuration does not require all component amino acid residues to lie within a single region of dihedral angles; instead, the alpha sheet contains residues of alternating dihedrals in the traditional right-handed (αR) and left-handed (αL) helical regions of Ramachandran space. Although the alpha sheet is only rarely observed in natural protein structures, it has been speculated to play a role in amyloid disease and it was found to be a stable form for amyloidogenic proteins in molecular dynamics simulations. Alpha sheets have also been observed in X-ray crystallography structures of designed peptides.

Glycopeptides are peptides that contain carbohydrate moieties (glycans) covalently attached to the side chains of the amino acid residues that constitute the peptide.

The Juliá–Colonna epoxidation is an asymmetric poly-leucine catalyzed nucleophilic epoxidation of electron deficient olefins in a triphasic system. The reaction was reported by Sebastian Juliá at the Chemical Institute of Sarriá in 1980, with further elaboration by both Juliá and Stefano Colonna.

The Nest is a type of protein structural motif. It is a small recurring anion-binding feature of both proteins and peptides. Each consists of the main chain atoms of three consecutive amino acid residues. The main chain NH groups bind the anions while the side chain atoms are often not involved. Proline residues lack NH groups so are rare in nests. About one in 12 of amino acid residues in proteins, on average, belongs to a nest.

In biochemistry, non-coded or non-proteinogenic amino acids are distinct from the 22 proteinogenic amino acids which are naturally encoded in the genome of organisms for the assembly of proteins. However, over 140 non-proteinogenic amino acids occur naturally in proteins and thousands more may occur in nature or be synthesized in the laboratory. Chemically synthesized amino acids can be called unnatural amino acids. Unnatural amino acids can be synthetically prepared from their native analogs via modifications such as amine alkylation, side chain substitution, structural bond extension cyclization, and isosteric replacements within the amino acid backbone. Many non-proteinogenic amino acids are important:

Bottromycin is a macrocyclic peptide with antibiotic activity. It was first discovered in 1957 as a natural product isolated from Streptomyces bottropensis. It has been shown to inhibit methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) among other Gram-positive bacteria and mycoplasma. Bottromycin is structurally distinct from both vancomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic, and methicillin, a beta-lactam antibiotic.

Halovir refers to a multi-analogue compound belonging to a group of oligopeptides designated as lipopeptaibols which have membrane-modifying capacity and are fungal in origin. These peptides display interesting microheterogeneity; slight variation in encoding amino acids gives rise to a mixture of closely related analogues and have been shown to have antibacterial/antiviral properties.