The Border Security Force (BSF) is India's border guarding organisation at its borders with Pakistan and Bangladesh. It is one of the seven Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF) of India, and was raised in the wake of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 "for ensuring the security of the borders of India and for related matters".

Armed Forces Act (AFSPA), 1958 is an act of the Parliament of India that grants special powers to the Indian Armed Forces to maintain public order in "disturbed areas". According to the Disturbed Areas Act, 1976 once declared 'disturbed', the area has to maintain status quo for a minimum of 3 months. One such act passed on 11 September 1958 was applicable to the Naga Hills, then part of Assam. In the following decades it spread, one by one, to the other Seven Sister States in India's northeast. Another one passed in 1983 and applicable to Punjab and Chandigarh was withdrawn in 1997, roughly 14 years after it came to force. An act passed in 1990 was applied to Jammu and Kashmir and has been in force since.

The insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir, also known as the Kashmir insurgency, is an ongoing separatist militant insurgency against the Indian administration in Jammu and Kashmir, a territory constituting the southwestern portion of the larger geographical region of Kashmir, which has been the subject of a territorial dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947.

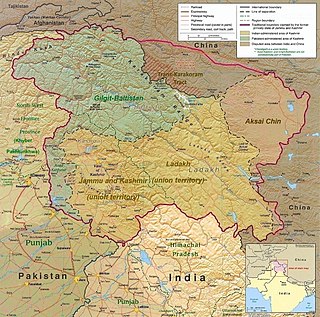

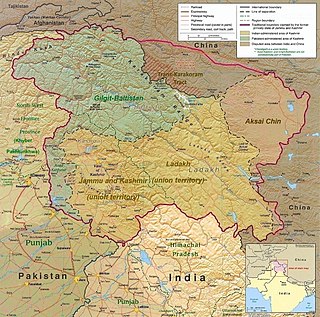

The Kashmir conflict is a territorial conflict over the Kashmir region, primarily between India and Pakistan and also between China and India in northeastern portion of the region. The conflict started after the partition of India in 1947 as both India and Pakistan claimed the entirety of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. It is a dispute over the region that escalated into three wars between India and Pakistan and several other armed skirmishes. India controls approximately 55% of the land area of the region that includes Jammu, the Kashmir Valley, most of Ladakh, the Siachen Glacier, and 70% of its population; Pakistan controls approximately 30% of the land area that includes Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan; and China controls the remaining 15% of the land area that includes the Aksai Chin region, the mostly uninhabited Trans-Karakoram Tract, and part of the Demchok sector.

Human rights in India is an issue complicated by the country's large size and population as well as its diverse culture, despite its status as the world's largest sovereign, secular, democratic republic. The Constitution of India provides for fundamental rights, which include freedom of religion. Clauses also provide for freedom of speech, as well as separation of executive and judiciary and freedom of movement within the country and abroad. The country also has an independent judiciary as well as bodies to look into issues of human rights.

The Sopore massacre refers to the killing of at least 43 civilians by the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) who were travelling on a bus from Bandipur to Sopore in Kashmir on 6 January 1993.

Papa II was an interrogation centre in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, operated by the Border Security Force (BSF) from the start of the Kashmir insurgency in 1989 until it was shut down in 1996.

The Gawkadal massacre was named after the Gawkadal bridge in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India, where, on 21 January 1990, the Indian paramilitary troops of the Central Reserve Police Force opened fire on a group of Kashmiri protesters in what has been described by some authors as "the worst massacre in Kashmiri history". At least 50 people were killed. According to survivors, the actual death toll may have been as high as 280. The massacre happened two days after the Government of India appointed Jagmohan as the Governor for a second time in a bid to control the mass protests by Kashmiris.

The Chattisinghpora, Pathribal, and Barakpora massacres refer to a series of three closely related incidents that took place in the Anantnag district of Jammu and Kashmir between 20 March 2000 and 3 April 2000 that left up to 49 Kashmiri civilians dead.

The 1993 Lal Chowk fire refers to the arson attack on the main commercial centre of downtown Srinagar, Kashmir, that took place on 10 April 1993. The fire is alleged by government officials to have been started by a crowd incited by militants, while civilians and police officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch and other organisations allege that the Indian Border Security Forces (BSF) set fire to the locality in retaliation for the burning of an abandoned BSF building by local residents. Over 125 civilians were killed in the conflagration and the ensuing shooting by BSF troops.

Lal Chowk is a city square in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India.

The Kunan Poshspora incident was an alleged mass rape that occurred on 23 February 1991 when unit(s) of the Indian security forces, after being fired upon by militants, launched a search operation in the twin villages of Kunan and Poshpora, located in Kashmir's remote Kupwara District. The residents of the neighbourhood stated that militants had fired on soldiers nearby, which prompted the operation. Some of the villagers claimed that many women were raped by soldiers that night. The first information report filed in the police station after a visit by the local magistrate reported the number of women alleging rape as 23. However, Human Rights Watch asserts that this number could be between 23 and 100. These allegations were denied by the army. The government determined that the evidence was not sufficient and issued a statement condemning the allegations as terrorist propaganda.

The Zakura And Tengpora Massacre was the killing of protesters calling for the implementation of a United Nations resolution regarding the plebiscite in Kashmir at Zakura Crossing and Tengpora Bypass Road in Srinagar on 1 March 1990, in which 26 people were killed and 14 injured by Indian forces. It led Amnesty International to issue an appeal for urgent action on Kashmir.

Human rights abuses in Jammu and Kashmir range from mass killings, enforced disappearances, torture, rape and sexual abuse to political repression and suppression of freedom of speech. The Indian Army, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), and Border Security Personnel (BSF) have been accused of committing severe human rights abuses against Kashmiri civilians. According to Seema Kazi, militant groups have also been held responsible for similar crimes, but the vast majority of abuses have been perpetrated by the armed forces of the Indian government.

Human rights abuses in Kashmir have been perpetrated by various belligerents in the territories controlled by both India and Pakistan since the two countries' conflict over the region began with their first war in 1947–1948, shortly after the partition of British India. The organized breaches of fundamental human rights in Kashmir are tied to the contested territorial status of the region, over which India and Pakistan have fought multiple wars. More specifically, the issue pertains to abuses committed in Indian-administered Kashmir and in Pakistani-administered Kashmir.

On 7 April 2015, Andhra Pradesh Police shot twenty suspected woodcutters in the Seshachalam forest in Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Red Sanders Anti-Smuggling Task Force DIG Kantha Rao said that the smugglers attacked the team with sickles, rods and axes. Asked if the attack could have been quelled without such fatalities, Rao said, "We gave them several warnings but they did not stop attacking us. There were over a hundred of them." Asked how many of his men were grievously injured, he said, "Nobody is seriously hurt from our side. Their superior training saved their lives."

The 2016–2017 unrest in Kashmir, also known as the Burhan aftermath, refers to violent protests in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, chiefly in the Kashmir Valley. It started after the killing of militan leader Burhan Wani by Indian security forces on 8 July 2016. Wani was a commander of the Kashmir-based Islamist militant organisation Hizbul Mujahideen.

The Kashmir conflict has been beset by large scale usage of sexual violence by multiple belligerents since its inception.

The 1990 Hawal Massacre was named after the Hawal area of Srinagar, Kashmir, where, on 21 May 1990, the Indian paramilitary troops of the Central Reserve Police Force opened fire on the peaceful funeral procession which was carrying the body of Mirwaiz Moulana Muhammad Farooq who was assassinated by unidentified gunmen at his Nageen Residence. The funeral procession was taking the body from SKIMS, Soura to Mirwaiz Manzil, Rajouri Kadal.