Related Research Articles

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2Si2O5(OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especially quartz and calcite. Shale is characterized by its tendency to split into thin layers (laminae) less than one centimeter in thickness. This property is called fissility. Shale is the most common sedimentary rock.

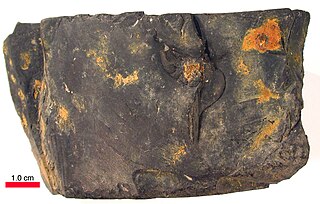

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the seams. It is typically hard but friable. Its quality is ranked higher than lignite and sub-bituminous coal, but lesser than anthracite. It is the most abundant rank of coal, with deposits found around the world, often in rocks of Carboniferous age. Bituminous coal is formed from sub-bituminous coal that is buried deeply enough to be heated to 85 °C (185 °F) or higher.

Sedimentology encompasses the study of modern sediments such as sand, silt, and clay, and the processes that result in their formation, transport, deposition and diagenesis. Sedimentologists apply their understanding of modern processes to interpret geologic history through observations of sedimentary rocks and sedimentary structures.

Kerogen is solid, insoluble organic matter in sedimentary rocks. It consists of a variety of organic materials, including dead plants, algae, and other microorganisms, that have been compressed and heated by geological processes. All the kerogen on earth is estimated to contain 1016 tons of carbon. This makes it the most abundant source of organic compounds on earth, exceeding the total organic content of living matter 10,000-fold.

Vitrinite is one of the primary components of coals and most sedimentary kerogens. Vitrinite is a type of maceral, where "macerals" are organic components of coal analogous to the "minerals" of rocks. Vitrinite has a shiny appearance resembling glass (vitreous). It is derived from the cell-wall material or woody tissue of the plants from which coal was formed. Chemically, it is composed of polymers, cellulose and lignin.

Inertinite refers to a group of partially oxidized organic materials or fossilized charcoals, all sharing the characteristic that they typically are inert when heated in the absence of oxygen. Inertinite is a common maceral in most types of coal. The main inertinite submacerals are fusinite, semifusinite, micrinite, macrinite and funginite, with semifusinite being the most common. From the perspective of coal combustion, inertinite can be burned to yield heat, but does not yield significant volatile fractions during coking.

A maceral is a component, organic in origin, of coal or oil shale. The term 'maceral' in reference to coal is analogous to the use of the term 'mineral' in reference to igneous or metamorphic rocks. Examples of macerals are inertinite, vitrinite, and liptinite.

In coal geology, liptinite is the finely-ground and macerated remains found in coal deposits. It replaced the term exinite as one of the four categories of kerogen. Liptinites were originally formed by spores, pollen, dinoflagellate cysts, leaf cuticles, and plant resins and waxes.

Organic geochemistry is the study of the impacts and processes that organisms have had on the Earth. It is mainly concerned with the composition and mode of origin of organic matter in rocks and in bodies of water. The study of organic geochemistry is traced to the work of Alfred E. Treibs, "the father of organic geochemistry." Treibs first isolated metalloporphyrins from petroleum. This discovery established the biological origin of petroleum, which was previously poorly understood. Metalloporphyrins in general are highly stable organic compounds, and the detailed structures of the extracted derivatives made clear that they originated from chlorophyll.

Organic-rich sedimentary rocks are a specific type of sedimentary rock that contains significant amounts (>3%) of organic carbon. The most common types include coal, lignite, oil shale, or black shale. The organic material may be disseminated throughout the rock giving it a uniform dark color, and/or it may be present as discrete occurrences of tar, bitumen, asphalt, petroleum, coal or carbonaceous material. Organic-rich sedimentary rocks may act as source rocks which generate hydrocarbons that accumulate in other sedimentary "reservoir" rocks. Potential source rocks are any type of sedimentary rock that the ability to dispel available carbon from within it. Good reservoir rocks are any sedimentary rock that has high pore-space availability. This allows the hydrocarbons to accumulate within the rock and be stored for long periods of time. Highly permeable reservoir rocks are also of interest to industry professionals, as they allow for the easy extraction of the hydrocarbons within. The hydrocarbon reservoir system is not complete however without a "cap rock". Cap rocks are rock units which have very low porosity and permeability, which trap the hydrocarbons within the units below as they try to migrate upwards.

Sedimentary organic matter includes the organic carbon component of sediments and sedimentary rocks. The organic matter is usually a component of sedimentary material even if it is present in low abundance. Petroleum and natural gas are particular examples of sedimentary organic matter. Coals and bitumen shales are examples of sedimentary rocks rich in sedimentary organic matter.

Cannel coal or candle coal is a type of bituminous coal, also classified as terrestrial type oil shale. Due to its physical morphology and low mineral content cannel coal is considered to be coal but by its texture and composition of the organic matter it is considered to be oil shale. Although historically the term cannel coal has been used interchangeably with boghead coal, a more recent classification system restricts cannel coal to terrestrial origin, and boghead coal to lacustrine environments.

The Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) underlies 1.4 million square kilometres (540,000 sq mi) of Western Canada including southwestern Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan, Alberta, northeastern British Columbia and the southwest corner of the Northwest Territories. This vast sedimentary basin consists of a massive wedge of sedimentary rock extending from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Canadian Shield in the east. This wedge is about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) thick under the Rocky Mountains, but thins to zero at its eastern margins. The WCSB contains one of the world's largest reserves of petroleum and natural gas and supplies much of the North American market, producing more than 450 million cubic metres per day of gas in 2000. It also has huge reserves of coal. Of the provinces and territories within the WCSB, Alberta has most of the oil and gas reserves and almost all of the oil sands.

Phytane is the isoprenoid alkane formed when phytol, a chemical substituent of chlorophyll, loses its hydroxyl group. When phytol loses one carbon atom, it yields pristane. Other sources of phytane and pristane have also been proposed than phytol.

Torbanite, also known historically as boghead coal or kerosene shale, is a variety of fine-grained black oil shale. It usually occurs as lenticular masses, often associated with deposits of Permian coals. Torbanite is classified as lacustrine type oil shale. A similar mineral, cannel coal, is classified as being a terrestrial form of oil shale, not a lacustrine type.

Oil shale geology is a branch of geologic sciences which studies the formation and composition of oil shales–fine-grained sedimentary rocks containing significant amounts of kerogen, and belonging to the group of sapropel fuels. Oil shale formation takes place in a number of depositional settings and has considerable compositional variation. Oil shales can be classified by their composition or by their depositional environment. Much of the organic matter in oil shales is of algal origin, but may also include remains of vascular land plants. Three major type of organic matter (macerals) in oil shale are telalginite, lamalginite, and bituminite. Some oil shale deposits also contain metals which include vanadium, zinc, copper, and uranium.

In petroleum geology, source rock is rock which has generated hydrocarbons or which could generate hydrocarbons. Source rocks are one of the necessary elements of a working petroleum system. They are organic-rich sediments that may have been deposited in a variety of environments including deep water marine, lacustrine and deltaic. Oil shale can be regarded as an organic-rich but immature source rock from which little or no oil has been generated and expelled. Subsurface source rock mapping methodologies make it possible to identify likely zones of petroleum occurrence in sedimentary basins as well as shale gas plays.

Pyrobitumen is a type of solid, amorphous organic matter. Pyrobitumen is mostly insoluble in carbon disulfide and other organic solvents as a result of molecular cross-linking, which renders previously soluble organic matter insoluble. Not all solid bitumens are pyrobitumens, in that some solid bitumens are soluble in common organic solvents, including CS

2, dichloromethane, and benzene-methanol mixtures.

Marie-Therese Mackowsky (1913-1986) was a German mineralogist.

Funginite is a maceral, a component, organic in origin, of coal or oil shale, that exhibits several different physical properties and characteristics under particular conditions, and its dimensions are based upon its source and place of discovery. Furthermore, it is primarily part of a group of macerals that naturally occur in rocks containing mostly carbon constituents, specifically coal. Due to its nature, research into the chemical structure and formula of funginite is considered limited and lacking. According to Chen et al. referencing ICCP, 2001, alongside the maceral secretinite, they "are both macerals of the inertinite group, which is more commonly known as fossilized charcoal, and were previously jointly classified as the maceral sclerotinite". In the scientific community, the discernment between the two does not remain entirely clear, but there are slight particular and specific differences in regards to the composition between both. It is also the product of fungal development on these carbon rich sedimentary rocks.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Pickel, W; Kalatizidis, S; Christanis, K; Cardott, B. J; Misz-Kennan, M; Hentschel, A; Hamor-Vido, M; Crosdale, P; Wagner, N (2017). "Classification of liptinite - ICCP System 1994". International Journal of Coal Geology. 169: 40–61. Bibcode:2017IJCG..169...40P. doi: 10.1016/j.coal.2016.11.004 .

- ↑ Hutton, A. C (1987). "Petrographic Classification of Oil Shales". International Journal of Coal Geology. 8 (3): 201–231. Bibcode:1987IJCG....8..203H. doi:10.1016/0166-5162(87)90032-2 – via Elsevier Science Publishers.

- 1 2 Littke, R; Baker, D. R; Leythaeuser, D (1987). "Microscopic and sedimentologic evidence for the generation and migration of hydrocarbons in Toarcian source rocks of different maturities". Advances in Organic Geochemistry. 13 (1–3): 549–559. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(88)90075-7.

- 1 2 Cook, A.C; Sherwood, N. R (1991). "Classification of oil shales, coals and other organic-rich rocks". Org. Geochem. 17 (2): 211–222. Bibcode:1991OrGeo..17..211C. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(91)90079-y.

- ↑ Taylor, G. H; Liu, S. Y; Teichmüller, M (1990). "Bituminite - A TEM view". International Journal of Coal Geology. 18 (1–2): 71–85. doi:10.1016/0166-5162(91)90044-j.

- ↑ Hutton, A. C (1995). Snape, Colin (ed.). "Organic Petrography: Principles and Techniques". Composition, Geochemistry and Conversion of Oil Shales. 455: 1–16.

- ↑ "International Committee for Coal and Organic Petrology". International Organization for Standardization (ISO).