Related Research Articles

Sharia is a religious law forming part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam, particularly the Quran and the hadith. In Arabic, the term sharīʿah refers to God's immutable divine law and is contrasted with fiqh, which refers to its human scholarly interpretations. The manner of its application in modern times has been a subject of dispute between Muslim fundamentalists and modernists.

Freedom of religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance in the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) is marked by Iranian culture, major religion and politics. The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran mandates that the official religion of Iran is Shia Islam and the Twelver Ja'fari school, and also mandates that other Islamic schools are to be accorded full respect, and their followers are free to act in accordance with their own jurisprudence in performing their religious rites. The Constitution of Iran stipulates that Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians are the only recognized religious minorities. The continuous presence of the country's pre-Islamic, non-Muslim communities, such as Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians, had accustomed the population to the participation of non-Muslims in society.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is an Islamic absolute monarchy in which Sunni Islam is the official state religion based on firm Sharia law. Non-Muslims must practice their religion in private and are vulnerable to discrimination and deportation. It has been stated that no law requires all citizens to be Muslim, but also that non-Muslims are not allowed to have Saudi citizenship. Children born to Muslim fathers are by law deemed Muslim, and conversion from Islam to another religion is considered apostasy and punishable by death. Blasphemy against Sunni Islam is also punishable by death, but the more common penalty is a long prison sentence. According to the U.S. Department of State's 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom, there have been 'no confirmed reports of executions for either apostasy or blasphemy' between 1913 and 2013.

The Supreme Court of Afghanistan, or Stera Mahkama, was the court of last resort in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. It was created by the Constitution of Afghanistan, which was approved on January 4, 2004. Its creation was called for by the Bonn Agreement, which read in part:

Apostasy in Islam is commonly defined as the abandonment of Islam by a Muslim, in word or through deed. It includes not only explicit renunciations of the Islamic faith by converting to another religion, but also blasphemy or heresy, through any action or utterance implying unbelief, including those denying a "fundamental tenet or creed" of Islam.

Iran is a constitutional, Islamic theocracy. Its official religion is the doctrine of the Twelver Jaafari School. Iran's law against blasphemy derives from Sharia. Blasphemers are usually charged with "spreading corruption on earth", or mofsed-e-filarz, which can also be applied to criminal or political crimes. The law against blasphemy complements laws against criticizing the Islamic regime, insulting Islam, and publishing materials that deviate from Islamic standards.

Sayed Parwez Kambaksh was born 24 July 1984 in Afghanistan. In late 2007, he was a student at Balkh University and a journalist for Jahan-e-Naw, a daily. On 27 October 2007, police arrested Kambaksh, and accused him of "blasphemy and distribution of texts defamatory of Islam". The authorities claimed that Kambaksh distributed writing posted on the Internet by Arash Bikhoda. Bikoda's writing criticizes the treatment of women under Islamic Law.

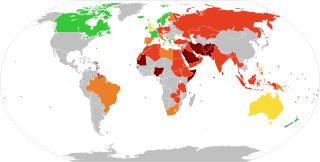

A blasphemy law is a law prohibiting blasphemy, where blasphemy is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence to a deity, or sacred objects, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable. According to Pew Research Center, about a quarter of the world's countries and territories (26%) had anti-blasphemy laws or policies as of 2014.

Blasphemy law in Indonesia is the legislation, presidential decrees, and ministerial directives that prohibit blasphemy in Indonesia.

Saudi Arabia's laws are an amalgam of rules from Sharia, royal decrees, royal ordinances, other royal codes and bylaws, fatwas from the Council of Senior Scholars and custom and practice.

A person who is accused of blasphemy in Yemen is often subject to vigilantism by governmental authorities. An accused person is subject to Sharia, which, according to some interpretations, prescribes death for blasphemy.

The main blasphemy law in Egypt is Article 98(f) of the Egyptian Penal Code. It penalizes: "whoever exploits and uses the religion in advocating and propagating by talk or in writing, or by any other method, extremist thoughts with the aim of instigating sedition and division or disdaining and contempting any of the heavenly religions or the sects belonging thereto, or prejudicing national unity or social peace."

The People's Democratic Republic of Algeria prohibits blasphemy against Islam by using legislation rather than by using Sharia. The penalty for blasphemy may be years of imprisonment as well as a fine. Every Algerian child has an opportunity to learn what blasphemy is because Islam is a compulsory subject in public schools, which are regulated jointly by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has Islam as its official religion, and the federation regards blasphemy as a very serious matter. The UAE uses the school system as well as censorship and control of the press and the broadcast media to prevent blasphemy. When blasphemy occurs, the Emirates have two court systems to mete out punishment.

Malaysia curbs blasphemy and any insult to religion or to the religious by rigorous control of what people in that country can say or do. Government-funded schools teach young Muslims the principles of Sunni Islam, and instruct young non-Muslims on morals. The government informs the citizenry on proper behavior and attitudes, and ensures that Muslim civil servants take courses in Sunni Islam. The government ensures that the broadcasting and publishing media do not create disharmony or disobedience. If someone blasphemes or otherwise engages in deviant behavior, Malaysia punishes such transgression with Sharia or through legislation such as the Penal Code.

Youcef Nadarkhani is an Iranian Christian pastor who was sentenced to death in Tehran as being a Christian having been born into Islam. Initial reports, including a 2010 brief from the Iranian Supreme court, stated that the sentence on Nadarkhani was based on the crime of apostasy, renouncing his Islamic faith. Government officials later claimed that the sentence was instead based on alleged violent crimes, specifically rape and extortion; however, no formal charges or evidence of violent crimes have been presented in court. According to Amnesty International and Nadarkhani's legal team, the Iranian government had offered leniency if he were to recant his Christianity. His lawyer Mohammad Ali Dadkhah stated that an appeals court upheld his sentence after he refused to renounce his Christian faith and convert to Islam In early September 2012, Nadarkhani was acquitted of apostasy, but found guilty of evangelizing Muslims, though he was immediately released as having served prison time. However, he was taken back into custody on Christmas Day 2012 and then released shortly afterwards on 7 January 2013.

According to a study by Humanists International (HI), Afghanistan is one of the seven countries in the world where being an atheist or a convert can lead to a death sentence. According to the 2012 WIN-Gallup Global Index of Religion and Atheism report, Afghanistan ranks among the countries where people are least likely to admit to being an atheist.

Ali Mohaqiq Nasab is a liberal Afghan Shi'ite cleric and a former editor-in-chief of Huqūqi Zan.

Capital punishment for non-violent offenses is allowed by law in many countries.

The situation for apostates from Islam varies markedly between Muslim-minority and Muslim-majority regions. In Muslim-minority countries "any violence against those who abandon Islam is already illegal". But in some Muslim-majority countries, religious violence is "institutionalised", and "hundreds and thousands of closet apostates" live in fear of violence and are compelled to live lives of "extreme duplicity and mental stress."

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "2008 Report on International Religious Freedom - Afghanistan". United States Department of State. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 Wright, Abi; Kristin Jones (11 October 2005). "Afghanistan: Editor goes on trial for blasphemy". Centre for Independent Journalism, Malaysia. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- 1 2 Wafa, Abdul Waheed; Carlotta Gall; Taimoor Shah (11 March 2009). "Afghan Court Backs Prison Term for Blasphemy". The New York Times . Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ Mineeia, Zainab (21 October 2008). "Afghanistan: Journalist Serving 20 Years for "Blasphemy"". IPS (Inter Press Service). Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ↑ Wiseman, Paul (31 January 2008). "Afghan student's death sentence hits nerve". USA Today. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ↑ Sengupta, Kim (7 September 2009). "Free at last: Student in hiding after Karzai's intervention". The Independent . Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ↑ "Supreme court confirms death sentence for two journalists for "blasphemy"". Reporters sans frontières. 6 August 2003. Retrieved 13 July 2009.[ permanent dead link ]