Related Research Articles

Freedom of religion in Pakistan is formally guaranteed by the Constitution of Pakistan for individuals of various religions and religious sects.

Freedom of speech and freedom of the press in Denmark are ensured by § 77 of the constitution:

In 2011, the then Algerian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika lifted a state of emergency that had been in place since the end of the Algerian Civil War in 2002, as a result of the Arab Spring protests that had occurred throughout the Arab world.

The Pakistan Penal Code outlaws blasphemy against any recognized religion, with punishments ranging from a fine to the death penalty. According to various human rights organizations, Pakistan's blasphemy laws have been used to persecute religious minorities and settle personal rivalries, frequently against other Muslims, rather than to safeguard religious sensibilities.

Iran is a constitutional, Islamic theocracy. Its official religion is the doctrine of the Twelver Jaafari School. Iran's law against blasphemy derives from Sharia. Blasphemers are usually charged with "spreading corruption on earth", or mofsed-e-filarz, which can also be applied to criminal or political crimes. The law against blasphemy complements laws against criticizing the Islamic regime, insulting Islam, and publishing materials that deviate from Islamic standards.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Pakistan. Although there have been numerous amendments to the Constitution, there is yet to be a provision prohibiting the death penalty as a punitive remedy.

The Indonesian constitution provides some degree of freedom of religion. The government generally respects religious freedom for the six officially recognized religions and/or folk religion. All religions have equal rights according to the Indonesian laws.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Algeria:

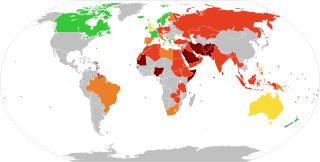

A blasphemy law is a law prohibiting blasphemy, which is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence to a deity, or sacred objects, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable. According to Pew Research Center, about a quarter of the world's countries and territories (26%) had anti-blasphemy laws or policies as of 2014.

Blasphemy law in Indonesia is the legislation, presidential decrees, and ministerial directives that prohibit blasphemy in Indonesia.

Saudi Arabia's laws are an amalgam of rules from Sharia, royal decrees, royal ordinances, other royal codes and bylaws, fatwas from the Council of Senior Scholars and custom and practice.

Afghanistan uses Sharia as its justification for punishing blasphemy. The punishments are among the harshest in the world. Afghanistan uses its law against blasphemy to persecute religious minorities, apostasy, dissenters, academics, and journalists.

The main blasphemy law in Egypt is Article 98(f) of the Egyptian Penal Code. It penalizes: "whoever exploits and uses the religion in advocating and propagating by talk or in writing, or by any other method, extremist thoughts with the aim of instigating sedition and division or disdaining and contempting any of the heavenly religions or the sects belonging thereto, or prejudicing national unity or social peace."

The Federal Republic of Nigeria operates two court systems. Both systems can punish blasphemy. The Constitution provides a customary (irreligious) system and a system that incorporates Sharia. The customary system prohibits blasphemy by section 204 of Nigeria's Criminal Code.

Islam is the state religion of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and most Jordanians are Sunni Muslims. The kingdom prevents blasphemy against any religion by education, by laws, and by policies that discourage non-conformity.

The People's Republic of Bangladesh went from being a secular state in 1971 to having Islam as the state religion in 1988. Despite its state religion, Bangladesh uses a secular penal code dating from 1860—the time of the British occupation. The penal code discourages blasphemy by a section that forbids "hurting religious sentiments." Other laws permit the government to confiscate and to ban the publication of blasphemous material. Government officials, police, soldiers, and security forces may have discouraged blasphemy by extrajudicial actions including torture. Schools run by the government have Religious Studies in the curriculum.

Malaysia curbs blasphemy and any insult to religion or to the religious by rigorous control of what people in that country can say or do. Government-funded schools teach young Muslims the principles of Sunni Islam, and instruct young non-Muslims on morals. The government informs the citizenry on proper behavior and attitudes, and ensures that Muslim civil servants take courses in Sunni Islam. The government ensures that the broadcasting and publishing media do not create disharmony or disobedience. If someone blasphemes or otherwise engages in deviant behavior, Malaysia punishes such transgression with Sharia or through legislation such as the Penal Code.

Capital punishment for offenses is allowed by law in some countries. Such offenses include adultery, apostasy, blasphemy, corruption, drug trafficking, espionage, fraud, homosexuality and sodomy, perjury, prostitution, sorcery and witchcraft, theft, and treason.

The situation for apostates from Islam varies markedly between Muslim-minority and Muslim-majority regions. In Muslim-minority countries, "any violence against those who abandon Islam is already illegal". But in some Muslim-majority countries, religious violence is "institutionalised", and "hundreds and thousands of closet apostates" live in fear of violence and are compelled to live lives of "extreme duplicity and mental stress."

Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code lays down the punishment for the deliberate and malicious acts, that are intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs. It is one of the Hate speech laws in India. This law prohibits blasphemy against all religions in India.

References

- ↑ Kjeilen, Tore (n.d.). "Algeria/Education". LookLex. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ↑ "Algeria — Education". Encyclopedia of the Nations. n.d. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "2008 Human Rights Report: Algeria". U.S. State Department. 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 Boyle, Kevin; Juliet Sheen (1997). Freedom of Religion and Belief . Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 0-415-15978-4.

- ↑ "Summary Prepared by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights: Algeria" (PDF). A/HRC/WG.6/1/DZA/3. United Nations Human Rights Council. 6 March 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ↑ Code pénal (PDF) (4 ed.). Algeria: O.N.T.E. 2005. p. 52. ISBN 9961-41-045-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ↑ Code pénal (PDF) (4 ed.). Algeria: O.N.T.E. 2005. p. 56. ISBN 9961-41-045-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ↑ "Country profile: Algeria". BBC. 10 April 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- 1 2 "Algeria: Christians Acquitted in Blasphemy Case". Compass Direct News. 29 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "Algeria drops cartoon blasphemy charges against journalists". Magharebia. 8 October 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "UPDATE: Algeria: Samia Smets acquitted". Women Living Under Muslim Laws. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.