Related Research Articles

Religious intolerance is intolerance of another's religious beliefs, practices, faith or lack thereof.

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a crime, including insulting the Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, speaking the sacred name in Judaism, and blasphemy of the Holy Spirit is an eternal sin in Christianity. It was also a crime under English common law.

The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) is a United Nations body whose mission is to promote and protect human rights around the world. The Council has 47 members elected for staggered three-year terms on a regional group basis. The headquarters of the Council are at the United Nations Office at Geneva in Switzerland.

Incitement to ethnic or racial hatred is a crime under the laws of several countries.

Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten's publication of satirical cartoons of the Islamic prophet Muhammad on September 30, 2005, led to violence, arrests, inter-governmental tension, and debate about the scope of free speech and the place of Muslims in the West. Many Muslims stressed that the image of Muhammad is blasphemous, while many Westerners defended the right of free speech. A number of governments, organizations, and individuals have issued statements defining their stance on the protests or cartoons.

The Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (CDHRI) is a declaration of the member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) first adopted in Cairo, Egypt, on 5 August 1990,, and later revised in 2020 and adopted on 28 November 2020. It provides an overview on the Islamic perspective on human rights. The 1990 version affirms Islamic sharia as its sole source, whereas the 2020 version does not specifically invoke sharia. The focus of this article is the 1990 version of the CDHRI.

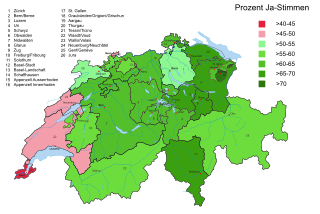

The federal popular initiative "against the construction of minarets" was a successful popular initiative in Switzerland to prevent the construction of minarets on mosques. In a November 2009 referendum, a constitutional amendment banning the construction of new minarets was approved by 57.5% of the participating voters. Only three of the twenty Swiss cantons and one half canton, mostly in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, opposed the initiative.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless, the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws.

Discussions of LGBT rights at the United Nations have included resolutions and joint statements in the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), attention to the expert-led human rights mechanisms, as well as by the UN Agencies.

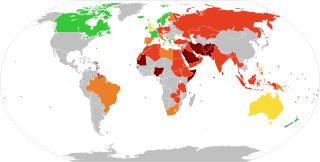

A blasphemy law is a law prohibiting blasphemy, which is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence to a deity, or sacred objects, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable. According to Pew Research Center, about a quarter of the world's countries and territories (26%) had anti-blasphemy laws or policies as of 2014.

Blasphemy is not a criminal offence under Australian federal law, but the de jure situation varies at state and territory level; it is currently not enforced in any Australian jurisdiction. The offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel in English common law were carried over to the Australian colonies and "received" into state law following Federation in 1901. The common-law offences have been abolished totally in Queensland and Western Australia, when those jurisdictions adopted criminal codes that superseded the common law. In South Australia, Victoria, and the Northern Territory the situation is ambiguous, as the local criminal codes do not mention blasphemy but also did not specifically abolish the common-law offences. In New South Wales and Tasmania, the criminal codes do include an offence of blasphemy or blasphemous libel, but the relevant sections are not enforced and generally regarded as obsolete.

Expression of racism in Latvia include racist discourse by politicians and in the media, as well as racially motivated attacks. European Commission against Racism and Intolerance notes some progress made in 2002–2007, mentioning also that a number of its earlier recommendations are not implemented or are only partially implemented. The UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance highlight three generally vulnerable groups and communities: ethnic Russians who immigrated to Latvia under USSR, the Roma community and recent non-European migrants. Besides, he notes a dissonance between "opinion expressed by most State institutions who view racism and discrimination as rare and isolated cases, and the views of civil society, who expressed serious concern regarding the structural nature of these problems".

The right to sexuality incorporates the right to express one's sexuality and to be free from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. Although it is equally applicable to heterosexuality, it also encompasses human rights of people of diverse sexual orientations, including lesbian, gay, asexual and bisexual people, and the protection of those rights. The right to sexuality and freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation is based on the universality of human rights and the inalienable nature of rights belonging to every person by virtue of being human.

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is a United Nations convention. A third-generation human rights instrument, the Convention commits its members to the elimination of racial discrimination and the promotion of understanding among all races. The Convention also requires its parties to criminalize hate speech and criminalize membership in racist organizations.

The UN Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief is a United Nations resolution, passed with consensus on November 25 1981. The "freedom of thought, conscience, and religion" was first outlined in article 18 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. The resolution further elaborates human rights regarding the freedom of religion. The declaration on human rights outlines religious freedoms, and the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and Discrimination asserts the "right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or whatever belief." The declaration was adopted by consensus 19 years after a request was made of the Economic and Social counsel to prepare a declaration addressing religious intolerance.

Online hate speech is a type of speech that takes place online with the purpose of attacking a person or a group based on their race, religion, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, disability, and/or gender. Online hate speech is not easily defined, but can be recognized by the degrading or dehumanizing function it serves.

The Prevention and Combating of Hate Crimes and Hate Speech Bill is a bill aimed at reducing offensive speech and curbing hate crimes in South Africa. The Bill was introduced in 2016 and sits before the South African National Assembly. Some of the stated intentions of the legislation include to "provide for the prevention of hate crimes and hate speech" and to "provide for effective enforcement measures" against those who express their "prejudice or intolerance towards the victim." The bill has been subject to much debate, with some groups expressing concern over the implications of restricting speech. Others have contended that the bill is necessary given the level of discrimination in South Africa and the decades-long Apartheid years before 1994.

Hate speech is public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation. Hate speech is "usually thought to include communications of animosity or disparagement of an individual or a group on account of a group characteristic such as race, colour, national origin, sex, disability, religion, or sexual orientation".

Shakthika Sathkumara is a writer and civil servant from Sri Lanka. He was charged under Section 3(1) of the ICCPR Act and Article 291(B) of the Penal Code of Sri Lanka, which covers propagating hatred and incitement of racial or religious violence, and faced up to ten years imprisonment. In February 2021, he was discharged.

Article 291A and 291B of the Penal Code of Sri Lanka restricts expressions made with the deliberate intent of hurting religious sentiments of a person. It carries a penalty of up to 2 years of imprisonment. Furthermore, the ICCPR Act and the Prevention of Terrorism Act has been used by the authorities to protect religion from criticism and insults.

References

- ↑ Dacey, Austin (12 June 2012). "Calvin's Geneva? The New International Discourse of Blasphemy". The Revealer. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ L Bennett Graham (25 March 2010). "No to an international blasphemy law". The Guardian.

- ↑ "UN anti-blasphemy measures have sinister goals, observers say". Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ↑ "Combating defamation of religions". UN. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Neo, Hui Min (25 March 2010). "UN rights body narrowly passes Islamophobia resolution". Canada.com. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Combating Defamation of Religions" (PDF). Becket Fund for Religious Liberty. February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2009.

- ↑ "Resolution 2000/84. Defamation of religions". ap.ohchr.org.

- ↑ "Resolution 2001/4". ap.ohchr.org.

- ↑ "Resolution 2002/9. Combating defamation of religion". UN Commission on Human Rights. E/CN.4/RES/2002/9.

- ↑ "A/RES/60/150 - E - A/RES/60/150". undocs.org. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ↑ "A/60/PV.64 - E - A/60/PV.64". undocs.org. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ↑ "A/RES/61/164 - E - A/RES/61/164". undocs.org. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ↑ "Vote on 19 December 2006" . Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "Resolution 4/9. Combating defamation of religions". United Nations Human Rights Council. 30 March 2007.

- ↑ "Resolution 4/10. Elimination of all forms of intolerance and of discrimination based on religion or belief". United Nations Human Rights Council.

- ↑ https://undocs.org/A/HRC/6/6 Report by Doudou Diène U. N. doc. A/HRC/6/6 (21 August 2007)

- ↑ "A/HRC/6/4 - E - A/HRC/6/4". undocs.org. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ↑ "A/RES/62/154 - E - A/RES/62/154". undocs.org. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ↑ "Vote on 18 December 2007" . Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "Resolution 7/19. Combating defamation of religions" (PDF). United Nations Human Rights Council. 27 March 2008.

- ↑ "High Commissioner's report 5 September 2008(A/HRC/9/25)" . Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ↑ "A/HRC/9/7 - E - A/HRC/9/7". undocs.org. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ↑ "Report by Doudou Diène" . Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "A/C.3/63/L.22/Rev.1 - E - A/C.3/63/L.22/Rev.1". undocs.org. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ↑ "Third Committee vote on defamation of religions Item 64(b) 24 November 2008" (PDF). Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ↑ "News & Media | UN GENEVA". www.ungeneva.org.

- ↑ International Humanist and Ethical Union (26 March 2009). "Human Rights Council Resolution "Combating Defamation of Religion" | International Humanist and Ethical Union". Humanists International. Iheu.org. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Amirbayov, Elchin (12 May 2009). "Draft report of the Human Rights Council on its tenth session" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. A/HRC/10/L.11.

- ↑ "U.N. rights council passes religious defamation resolution". Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA). 26 March 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ↑ MacInnis, Laura (26 March 2009). "UNHRC Resolution 26 March 2009". Reuters. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ↑ "Report of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, Githu Muigai, on the manifestations of defamation of religions, and in particular on the serious implications of Islamophobia, on the enjoyment of all rights by their followers" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. A/HRC/12/38.

- ↑ "A/64/209 - E - A/64/209". undocs.org. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ↑ "General Assembly, Human Rights Council, 12th session, Agenda item 3" (PDF). United States General Assembly. A/HRC/12/L.14/Rev.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- 1 2 "Unhchr.ch - unhchr Resources and Information".

- ↑ "UNHRC: Egypt-U.S. Resolution Concerns Rights Activists Supporting Freedom to Challenge Religious Views :: Responsible for Equality And Liberty (R.E.A.L.)". Realcourage.org. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Bayefsky, Anne (5 October 2009). "You Can't Say That". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ↑ "Ad Hoc Committee on the elaboration of complementary standards". www2.ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012.

- ↑ ""Defamation of Religion" archive at View from Geneva". Blog.unwatch.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ "Durban Ad Hoc Committee: Day 4 Afternoon at View from Geneva". Blog.unwatch.org. 23 October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ "OIC Document to Ad Hoc Committee" (PDF). 29 October 2009.

- ↑ "Developments - Third Committee draft resolution on combating defamation of religions (Syria, Belarus, Venezuela)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "Developments – Vote on Third Committee resolution on combating defamation of religions (A/C.3/64/L.27). 81 in favor – 55 against – 43 abstentions". Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "General Assembly Adopts 56 Resolutions, 9 Decisions Recommended by Third Committee on Broad Range of Human Rights, Social, Cultural Issues". Un.org. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Staff (2010). "Resolution Adopted by the Human Rights Council 13/16 - Combating the defamation of religions". United Nations . Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ McGonagle, T.; Donders, Y. (2015). The United Nations and Freedom of Expression and Information. Cambridge University Press. p. 397. ISBN 978-1-107-08386-8.

- ↑ Islamic bloc drops U.N. drive on defaming religion Reuters 25 March 2011

- ↑ Resolution 16/18 Berkley Centre for Religion, Peace & World Affairs Archived 19 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine , Georgetown University 21 March 2011

- ↑ Mission of the United States, Geneva, Switzerland: Joint Statement on Combating Intolerance, Discrimination and Violence

- ↑ "International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Human Rights Committee, 102nd session; General comment No. 34" (PDF). United Nations.

- ↑ Austin Dacey (11 August 2011). "United Nations Affirms the Human Right to Blaspheme". Religion Dispatches.

- ↑ NEWS Organization of Islamic Cooperation sponsors resolution on religious tolerance adopted by the Third Committee of the UN General Assembly - 2012-11-28