Ijtihad is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a legal question. It is contrasted with taqlid. According to classical Sunni theory, ijtihad requires expertise in the Arabic language, theology, revealed texts, and principles of jurisprudence, and is not employed where authentic and authoritative texts are considered unambiguous with regard to the question, or where there is an existing scholarly consensus (ijma). Ijtihad is considered to be a religious duty for those qualified to perform it. An Islamic scholar who is qualified to perform ijtihad is called as a "mujtahid".

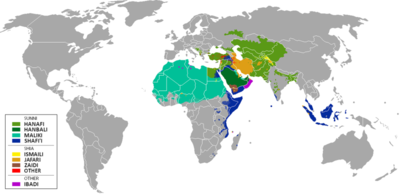

The Hanbali school is one of the four major traditional Sunni schools (madhahib) of Islamic jurisprudence. It is named after the Arab scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal, and was institutionalized by his students. The Hanbali madhhab is the smallest of four major Sunni schools, the others being the Hanafi, Maliki and Shafi`i.

The Mālikī school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary sources. Unlike other Islamic fiqhs, Maliki fiqh also considers the consensus of the people of Medina to be a valid source of Islamic law.

A Madhhab is a school of thought within fiqh.

Abū ʿAbdillāh Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī was an Arab Muslim theologian, writer, and scholar, who was one of the first contributors of the principles of Islamic jurisprudence. Often referred to as 'Shaykh al-Islām', al-Shāfi‘ī was one of the four great Sunni Imams, whose legacy on juridical matters and teaching eventually led to the formation of Shafi'i school of fiqh. He was the most prominent student of Imam Malik ibn Anas, and he also served as the Governor of Najar. Born in Gaza in Palestine, he also lived in Mecca and Medina in the Hejaz, Yemen, Egypt, and Baghdad in Iraq.

Nuʿmān ibn Thābit ibn Zūṭā ibn Marzubān, commonly known by his kunyaAbū Ḥanīfa, or reverently as Imam Abū Ḥanīfa by Sunni Muslims, was a Persian Sunni Muslim theologian and jurist who became the eponymous founder of the Hanafi school of Sunni jurisprudence, which has remained the most widely practiced law school in the Sunni tradition, predominates in Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, Balkans, Russia, Circassia, Chechnya, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Muslims in India, Turkey, and some parts of the Arab world.

Principles of Islamic jurisprudence, also known as uṣūl al-fiqh, are traditional methodological principles used in Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) for deriving the rulings of Islamic law (sharia).

The Muwaṭṭaʾ or Muwatta Imam Malik of Imam Malik (711–795) written in the 8th-century, is one of the earliest collections of hadith texts comprising the subjects of Islamic law, compiled by the Imam, Malik ibn Anas. Malik's best-known work, Al-Muwatta was the first legal work to incorporate and combine hadith and fiqh.

Dhia' ul-Dīn 'Abd al-Malik ibn Yūsuf al-Juwaynī al-Shafi'ī was a Persian Sunni scholar famous for being the foremost leading jurisconsult, legal theorist and Islamic theologian of his time. His name is commonly abbreviated as Al-Juwayni; he is also commonly referred to as Imam al Haramayn meaning "leading master of the two holy cities", that is, Mecca and Medina. He acquired the status of a mujtahid in the field of fiqh and usul al-fiqh. Highly celebrated as one of the most important and influential thinkers in the Shafi'i school of orthodox Sunni jurisprudence, he was considered as the virtual second founder of the Shafi'i school, after its first founder Imam al-Shafi'i. He was also considered a major figurehead within the Ash'ari school of theology where he was ranked equal to the founder, Imam al-Ash'ari. He was given the honorific titles of Shaykh of Islam, The Glory of Islam, The Absolute Imam of all Imams.

Ahl al-Ḥadīth was an Islamic school of Sunni Islam that emerged during the 2nd/3rd Islamic centuries of the Islamic era as a movement of hadith scholars who considered the Quran and authentic hadith to be the only authority in matters of law and creed. Its adherents have also been referred to as traditionalists and sometimes traditionists. The traditionalists constituted the most authoritative and dominant bloc of Sunni orthodoxy prior to the emergence of mad'habs during the fourth Islamic century.

Ya'qub ibn Ibrahim al-Ansari, better known as Abu Yusuf (d.798) was a student of jurist Abu Hanifa (d.767) who helped spread the influence of the Hanafi school of Islamic law through his writings and the government positions that he held.

Abu Ja'far Ahmad al-Tahawi, or simply aṭ-Ṭaḥāwī, was an Egyptian Arab Hanafi jurist and Traditionalist theologian. He studied with his uncle al-Muzani and was a Shafi'i jurist, before then changing to the Hanafi school. He is known for his work al-'Aqidah al-Tahawiyyah, a summary of Sunni Islamic creed which influenced Hanafis in Egypt.

Muhammad b. Ahmad b. Abi Sahl Abu Bakr al-Sarakhsi, was a Persian jurist and also an Islamic scholar of the Hanafi school of thought. He was traditionally known as Shams al-A'imma.

Various sources of Islamic Laws are used by Islamic jurisprudence to elaborate the body of Islamic law. In Sunni Islam, the scriptural sources of traditional jurisprudence are the Holy Qur'an, believed by Muslims to be the direct and unaltered word of God, and the Sunnah, consisting of words and actions attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the hadith literature. In Shi'ite jurisprudence, the notion of Sunnah is extended to include traditions of the Imams.

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan ibn Farqad ash-Shaybānī, the father of Muslim international law, was an Arab jurist and a disciple of Abu Hanifa, Malik ibn Anas and Abu Yusuf.

The Shafiʽi school, also known as Madhhab al-Shāfiʿī, is one of the four major traditional schools of religious law (madhhab) in the Sunnī branch of Islam. It was founded by Arab theologian Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī, "the father of Muslim jurisprudence", in the early 9th century.

Shaykh Abul Wafa Al Afghani is one of the former Shaykh Ul Fiqh of Jamia Nizamia, Hyderabad. He was known for his contributions to Islamic sciences.

Abu Musa ʿĪsā b. Abān was an early Sunni Islamic scholar who followed the Hanafi madhhab. Although none of his own works have survived to today, he was quoted extensively by early Hanafi scholars such as Al-Jassas in regards to his views on Hanafi usul al-fiqh. Having studied under Abu Hanifa's student, Muhammad al-Shaybani, ibn Abān's views on the sources of law can be assumed to be representative of Abu Hanifa's.

Kitab al-Athar, is one of the earlier Hadith books compiled by Imam Muhammad al-Shaybani, the student of Imam Abu Hanifa. This book is sometime referred to Imam Abu Hanifa.

Abū Isḥāq Ibrāhīm ibn ʿAlī al-Shīrāzī was a prominent Persian Shafi'i-Ash'ari scholar, debater and the second teacher،after Ibn Sabbagh al-Shafei, at the Nizamiyya school in Baghdad, which was built in his honour by the vizier (minister) of the Seljuk Empire Nizam al-Mulk.