Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Different cultures have employed forms of astrology since at least the 2nd millennium BCE, these practices having originated in calendrical systems used to predict seasonal shifts and to interpret celestial cycles as signs of divine communications. Most, if not all, cultures have attached importance to what they observed in the sky, and some—such as the Hindus, Chinese, and the Maya—developed elaborate systems for predicting terrestrial events from celestial observations. Western astrology, one of the oldest astrological systems still in use, can trace its roots to 19th–17th century BCE Mesopotamia, from where it spread to Ancient Greece, Rome, the Islamic world, and eventually Central and Western Europe. Contemporary Western astrology is often associated with systems of horoscopes that purport to explain aspects of a person's personality and predict significant events in their lives based on the positions of celestial objects; the majority of professional astrologers rely on such systems.

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north and south of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. Also within this zodiac belt appear the Moon and the brightest planets, along their orbital planes. The zodiac is divided along the ecliptic into 12 equal parts ("signs"), each occupying 30° of celestial longitude. These signs roughly correspond to the astronomical constellations with the following modern names: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces.

Herman of Carinthia, also called Hermanus Dalmata or Sclavus Dalmata, Secundus, by his own words born in the "heart of Istria", was a philosopher, astronomer, astrologer, mathematician and translator of Arabic works into Latin.

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣūfī was an Iranian Muslim astronomer. His work Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib, written in 964, included both textual descriptions and illustrations. The Persian polymath Al-Biruni wrote that al-Ṣūfī's work on the ecliptic was carried out in Shiraz. Al-Ṣūfī lived at the Buyid court in Isfahan.

The House of Wisdom, also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, was believed to be a major Abbasid-era public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad. In popular reference, it acted as one of the world's largest public libraries during the Islamic Golden Age, and was founded either as a library for the collections of the fifth Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid in the late 8th century or as a private collection of the second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur to house rare books and collections of poetry in the Arabic and Persian language. During the reign of the seventh Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun, it was turned into a public academy and a library.

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī aṣ-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī, usually called al-Battānī, a name that was in the past Latinized as Albategnius, was an astronomer, astrologer and mathematician, who lived and worked for most of his life at Raqqa, now in Syria. He is considered to be the greatest and most famous of the astronomers of the medieval Islamic world.

Astrological belief in correspondences between celestial observations and terrestrial events have influenced various aspects of human history, including world-views, language and many elements of social culture.

An orbital node is either of the two points where an orbit intersects a plane of reference to which it is inclined. A non-inclined orbit, which is contained in the reference plane, has no nodes.

Astrology and astronomy were archaically treated together, but gradually distinguished through the Late Middle Ages into the Age of Reason. Developments in 17th century philosophy resulted in astrology and astronomy operating as independent pursuits by the 18th century.

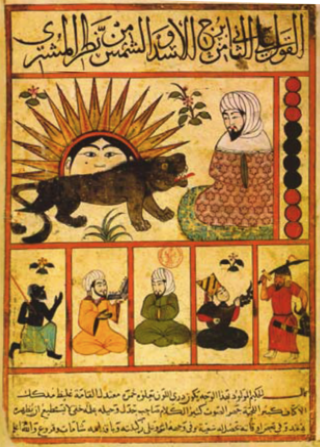

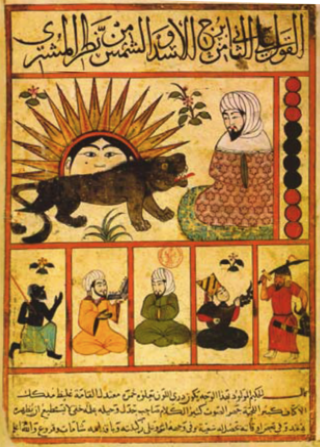

Abu Ma‘shar al-Balkhi, Latinized as Albumasar, was an early Persian Muslim astrologer, thought to be the greatest astrologer of the Abbasid court in Baghdad. While he was not a major innovator, his practical manuals for training astrologers profoundly influenced Muslim intellectual history and, through translations, that of western Europe and Byzantium.

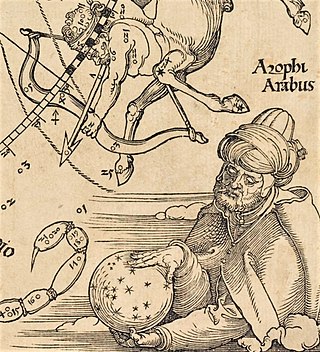

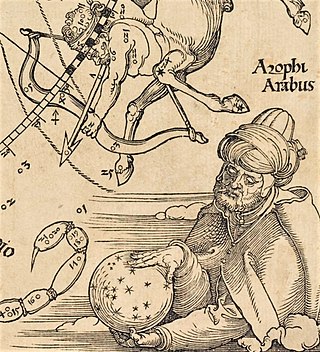

Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī, known as Mashallah, was an 8th century Persian Jewish astrologer, astronomer, and mathematician. Originally from Khorasan, he lived in Basra during the reigns of the Abbasid caliphs al-Manṣūr and al-Ma’mūn, and was among those who introduced astrology and astronomy to Baghdad. The bibliographer ibn al-Nadim described Mashallah "as virtuous and in his time a leader in the science of jurisprudence, i.e. the science of judgments of the stars". Mashallah served as a court astrologer for the Abbasid caliphate and wrote works on astrology in Arabic. Some Latin translations survive.

Shams ad-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb az-Zurʿī d-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī , commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya or Ibn al-Qayyim for short, or reverentially as Imam Ibn al-Qayyim in Sunni tradition, was an important medieval Islamic jurisconsult, theologian, and spiritual writer. Belonging to the Hanbali school of orthodox Sunni jurisprudence, of which he is regarded as "one of the most important thinkers," Ibn al-Qayyim was also the foremost disciple and student of Ibn Taymiyyah, with whom he was imprisoned in 1326 for dissenting against established tradition during Ibn Taymiyyah's famous incarceration in the Citadel of Damascus.

Tetrabiblos, also known as Apotelesmatiká and in Latin as Quadripartitum, is a text on the philosophy and practice of astrology, written by the Alexandrian scholar Claudius Ptolemy in Koine Greek during the 2nd century AD.

Medieval Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age, and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle East, Central Asia, Al-Andalus, and North Africa, and later in the Far East and India. It closely parallels the genesis of other Islamic sciences in its assimilation of foreign material and the amalgamation of the disparate elements of that material to create a science with Islamic characteristics. These included Greek, Sassanid, and Indian works in particular, which were translated and built upon.

George Saliba is an American historian who is Professor of Arabic and Islamic Science at the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies, Columbia University, New York, where he has been since 1979. Saliba is currently the founding director of the Farouk Jabre Center for Arabic & Islamic Science & Philosophy and the Jabre-Khwarizmi Chair in the History Department.

Islamic cosmology is the cosmology of Islamic societies. Islamic cosmology is not a single unitary system, but is inclusive of a number of cosmological systems, including Quranic cosmology, the cosmology of the Hadith collections, as well as those of Islamic astronomy and astrology. Broadly, cosmological conceptions themselves can be divided into thought concerning the physical structure of the cosmos (cosmography) and the origins of the cosmos (cosmogony).

Sahl ibn Bishr al-Israili, also known as Rabban al-Tabari and Haya al-Yahudi, was a Jewish or Syriac Christian astrologer, astronomer and mathematician from Tabaristan. He was the father of Ali ibn Sahl the famous scientist and physician, who became a convert to Islam.

Egyptian astronomy began in prehistoric times, in the Predynastic Period. In the 5th millennium BCE, the stone circles at Nabta Playa may have made use of astronomical alignments. By the time the historical Dynastic Period began in the 3rd millennium BCE, the 365 day period of the Egyptian calendar was already in use, and the observation of stars was important in determining the annual flooding of the Nile.

Astrology refers to the study of the movements and relative positions of celestial bodies interpreted as having an influence on human affairs and the natural world. In early Islamic history, astrology, was "by far" the most popular of the "numerous practices attempting to foretell future events or discern hidden things", according to historian Emilie Savage-Smith.

Ibn Hibintā was a Christian in Iraq known from an Arabic manuscript on Islamic astrology al-Mughnī fī aḥkām al-nujūm, the second part of which is preserved in Munich.