Regional offices

BORDA's main areas of operation are South Asia, including Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Nepal; Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, and Vietnam; Africa, comprising Mali and the SADC region states of Lesotho, Zambia, South Africa, and Tanzania; West & Central Asia, including Afghanistan and Iraq; and Latin America and the Caribbean, including Cuba, Ecuador, Haiti, Mexico, and Nicaragua.

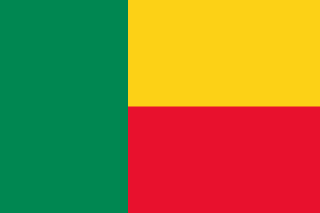

Africa

In September 2006, BORDA started the SADC BNS program through cooperation with TED (Technology for Economic Development), a Lesotho-based NGO. In February 2010, a regional office was established in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The regional office coordinates the program activities, facilitates a constantly growing BNS network within the SADC region and links up with BNS networks in South and South-East Asia. Further, BORDA cooperates with the Water and Sanitation Association of Zambia (WASAZA), based in Lusaka. The BORDA BNS network develops and delivers the following service packages: decentralized wastewater and urban sludge management; community-based sanitation (CBS) with integrated wastewater treatment for community and public sanitation centers and simplified sewer systems; school-based sanitation (SBS); decentralized solid waste management (DESWAM); biogas technologies; city-wide planning; health and hygiene education (HE); health impact assessment (HIA); and quality management. All service packages are adapted to the conditions and requirements of the individual country and are supported by an adequate quality management system (QMS).

In February 2009, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between BORDA and the Department of Water and Sanitation of the eThekwini Municipality (EWS) in the province KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, for a demonstration and research DEWATS plant to be designed, constructed, commissioned and operated at Newlands-Mashu, Durban. In October 2010, the biogas settler and the anaerobic baffled reactors (ABR) were seeded with biomass.

In June 2010, EWS, HERING South Africa, the Pollution Research Group (PRG) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), and BORDA agreed to cooperate to achieve the transfer of technology and know-how for the planning, installation, and operation of prefabricated community ablution blocks (CABs) to offer improved sanitation services to communities. Based on this Public-Private-Partnership-Project BORDA SADC established a new office in Shakas Head, in the north of Durban. The premises are shared with HERING South Africa.

South Asia

BORDA has worked in India since 1979, making it the oldest region to be served by the organization. Programs implemented span the range of BORDA services, from Decentralized Wastewater Treatment (DEWATS) to Decentralized Energy Supplies.

Currently, BORDA-South Asia (BORDA-SA) works in nine Indian states, as well as neighboring regions. In Nepal, BORDA co-operates with ENPHO. BORDA-SA and its partners have been contracted by international development organizations, including GIZ (Germany, in particular with the former GTZ and In Went), AusAID (Australia), and CEU, as well as national and local governments.

BORDA-SA supports a development cooperation network of 13 partner organizations and, by extension, over 100 development experts in providing basic needs services. Over 110 DEWATS projects have been implemented, together with more than 65 Decentralized Energy Supplies and 60 Water Supplies.

Southeast Asia

The main emphasis of BORDA SEA is DEWATS, in particular DEWATS CBS, SME's and the establishment of community-based organizations to provide sustainable operation and maintenance of the facilities. For upscaling the DESWAM (decentralized solid waste management for low-income urban communities) service package, BORDA SEA develops, in cooperation with IDRC (International Research Development Centre), a pro-poor carbon financing scheme under the Kyoto protocol.

In Indonesia, BORDA places a strong emphasis on the enhancement of DESWAM as well as continuing the national program of community-based sanitation (SANIMAS) through the dissemination of DEWATS. Best practices are transferred into technical and social implementation standard as well as improving the involved human resources capacity through training and certification.

The working group on Indonesia's national policy on water supply and sanitation is cooperating with BORDA and its local NGO partners as the main supporting network for community-based sanitation (CBS) with more than 500 implementations, including school-based sanitation and 14 DESWAM, until the end of 2010. Local NGO partners are Bilious, LPTP (Lembaga Engemann Technology Pedestal—Center for Community-Based Environmental Technology), and B.E.S.T.

In the Philippines, BORDA is cooperating with BNS Philippines to introduce DEWATS as a viable option for wastewater and environmental health problems in urban areas. Transferring know-how was conducted by Indonesian experts within the context of the BORDA south-south dissemination program. By now, BNS is a well-known service provider for DEWATS in the Philippines.

In Cambodia, specialists on DEWATS from Indonesia have been facilitated by BORDA and its partner organization, ESC (Environmental Services Cambodia), to enhance its capacity concerning DEWATS know-how. 3 DEWATS plants were inaugurated in 2010. Cooperation with national and international stakeholders will allow the start-up of DEWATS as an application for wastewater management in Cambodia, mainly for communities, schools and hospitals.

In Vietnam, the BORDA maintains a branch office. Indonesian specialists support the capacity building at the Vietnam Partners at the Vietnam Institute for Water Resources concerning DEWATS applications. In earlier years, the organization implemented the Hydraulic Ram (Hyram) technology as well as the use of biogas, energy-saving stoves, and solar panels, supported the introduction of HPC (Hydro Power Centre)'s turbine pumps and Decentralized Wastewater Treatment System (DEWATS) technology.

In Laos, BORDA opened a project office in February 2013 to implement DEWATS service packages in one of Southeast Asia's least developed countries. Institutional cooperation takes place at the national and local level, particularly with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport and the Department of Housing and Urban Planning, to promote both improved public health within low-income urban and peri-urban settlements, and the reduction of organic pollution of precious fresh water sources for the benefit of the Lao people and nation.

West & Central Asia

Under the project title “Capacity Building for local craftsmen and small medium enterprises for the sustainable implementation of decentralized wastewater treatment systems (DEWATS)”, BORDA has run project offices in Kabul and Herat since July 2012 with projects focused on vocational training.

Many years of civil war and military intervention have brought about a massive destruction of infrastructure and the loss of capacities for civil reconstruction in Afghanistan.

The current growth of the country's urban centers intensifies the need for feasible waste disposal solutions and increases the demand for trained staff in the water, sanitation, and hygiene sectors.

BORDA Afghanistan promotes DEWATS through training programs and learning projects. An emphasis is given to glass-fiber reinforced plastic (GRFP) technologies, which reduce the risk and cost of implementation. BORDA also provides school-based Sanitation (SBh), Health & Hygiene Education (Hei and Health Impact Assessments (HIA) in Afghanistan. So far, such services have been deployed hospitalism's, Hospitals and Mosques in the provinces Kabul, Bamiyan Balkh, Badakhshan, Herat, and Nangahar.

BORDA Afghanistan coordinates closely with national institutions such as the Ministry of Urban Development Affairs and the Environmental Protection Agency. For the vocational training of Afghan craftsmen and small-scale entrepreneurs, BORDA cooperates with its local partners.