Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related artistic movements in music, literature, and architecture. In Cubist works of art, the subjects are analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstract form—instead of depicting objects from a single perspective, the artist depicts the subject from multiple perspectives to represent the subject in a greater context. Cubism has been considered the most influential art movement of the 20th century. The term cubism is broadly associated with a variety of artworks produced in Paris or near Paris (Puteaux) during the 1910s and throughout the 1920s.

The Peggy Guggenheim Collection is an art museum on the Grand Canal in the Dorsoduro sestiere of Venice, Italy. It is one of the most visited attractions in Venice. The collection is housed in the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, an 18th-century palace, which was the home of the American heiress Peggy Guggenheim for three decades. She began displaying her private collection of modern artworks to the public seasonally in 1951. After her death in 1979, it passed to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, which opened the collection year-round from 1980.

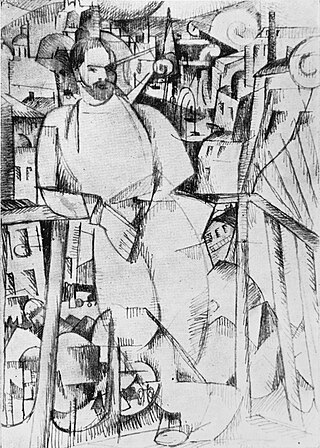

Jean Dominique Antony Metzinger was a major 20th-century French painter, theorist, writer, critic and poet, who along with Albert Gleizes wrote the first theoretical work on Cubism. His earliest works, from 1900 to 1904, were influenced by the neo-Impressionism of Georges Seurat and Henri-Edmond Cross. Between 1904 and 1907, Metzinger worked in the Divisionist and Fauvist styles with a strong Cézannian component, leading to some of the first proto-Cubist works.

The 1913 Armory Show, also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, was organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. It was the first large exhibition of modern art in America, as well as one of the many exhibitions that have been held in the vast spaces of U.S. National Guard armories.

Albert Gleizes was a French artist, theoretician, philosopher, a self-proclaimed founder of Cubism and an influence on the School of Paris. Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger wrote the first major treatise on Cubism, Du "Cubisme", 1912. Gleizes was a founding member of the Section d'Or group of artists. He was also a member of Der Sturm, and his many theoretical writings were originally most appreciated in Germany, where especially at the Bauhaus his ideas were given thoughtful consideration. Gleizes spent four crucial years in New York, and played an important role in making America aware of modern art. He was a member of the Society of Independent Artists, founder of the Ernest-Renan Association, and both a founder and participant in the Abbaye de Créteil. Gleizes exhibited regularly at Léonce Rosenberg's Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in Paris; he was also a founder, organizer and director of Abstraction-Création. From the mid-1920s to the late 1930s much of his energy went into writing, e.g., La Peinture et ses lois, Vers une conscience plastique: La Forme et l’histoire and Homocentrisme.

John Quinn was an Irish-American cognoscente of the art world and a lawyer in New York City who fought to overturn censorship laws restricting modern literature and art from entering the United States.

The Section d'Or, also known as Groupe de Puteaux or Puteaux Group, was a collective of painters, sculptors, poets and critics associated with Cubism and Orphism. Based in the Parisian suburbs, the group held regular meetings at the home of the Duchamp brothers in Puteaux and at the studio of Albert Gleizes in Courbevoie. Active from 1911 to around 1914, members of the collective came to prominence in the wake of their controversial showing at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1911. This showing by Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Henri le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger and Marie Laurencin, created a scandal that brought Cubism to the attention of the general public for the first time.

Le Dépiquage des Moissons, also known as Harvest Threshing, and The Harvesters, is an immense oil painting created in 1912 by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes (1881–1953). It was first revealed to the general public at the Salon de la Section d'Or, Galerie La Boétie in Paris, October 1912. This work, along with La Ville de Paris by Robert Delaunay, is the largest and most ambitious Cubist painting undertaken during the pre-War Cubist period. Formerly in the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, this monumental painting by Gleizes is exhibited at the National Museum of Western Art, in Tokyo, Japan.

The Bathers {French: Les Baigneuses) is a large oil painting created at the outset of 1912 by the French artist Albert Gleizes. It was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris during the spring of 1912; the Salon de la Société Normande de Peinture Moderne, Rouen, summer 1912; and the Salon de la Section d'Or, autumn 1912. The painting was reproduced in Du "Cubisme", written by Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger the same year: the first and only manifesto on Cubism. Les Baigneuses, while still 'readable' in the figurative or representational sense, exemplifies the mobile, dynamic fragmentation of form and multiple perspective characteristic of Cubism at the outset of 1912. Highly sophisticated, both in theory and in practice, this aspect of simultaneity would soon become identified with the practices of the Section d'Or group. Gleizes deploys these techniques in "a radical, personal and coherent manner". Purchased in 1937, the painting is exhibited in the permanent collection of the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

The Blue Bird is an oil painting created in 1912–1913 by the French artist and theorist Jean Metzinger. L'Oiseau bleu, one of Metzinger's most recognizable and frequently referenced works, was first exhibited in Paris at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1913, several months after the publication of the first Cubist manifesto, Du "Cubisme", written by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes (1912). It was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in Berlin.

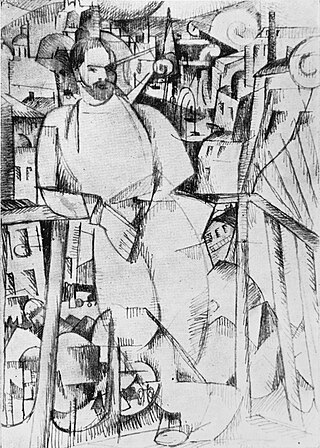

Man on a Balcony, is a large oil painting created in 1912 by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes (1881–1953). The painting was exhibited in Paris at the Salon d'Automne of 1912. The Cubist contribution to the salon created a controversy in the French Parliament about the use of public funds to provide the venue for such 'barbaric art'. Gleizes was a founder of Cubism, and demonstrates the principles of the movement in this monumental painting with its projecting planes and fragmented lines. The large size of the painting reflects Gleizes's ambition to show it in the large annual salon exhibitions in Paris, where he was able with others of his entourage to bring Cubism to wider audiences.

The Hunt is a painting created in 1911 by the French artist Albert Gleizes. The work was exhibited at the 1911 Salon d'Automne ; Jack of Diamonds, Moscow, 1912; the Salon de la Société Normande de Peinture Moderne, Rouen, summer 1912; the Salon de la Section d'Or, Galerie La Boétie, 1912, Le Cubisme, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, 1953, and several major exhibitions during subsequent years.

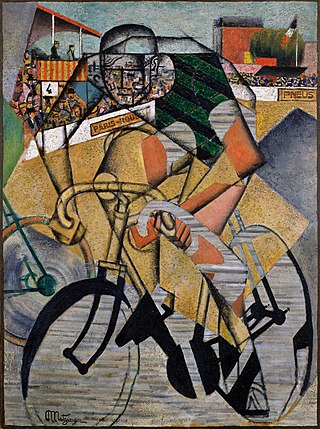

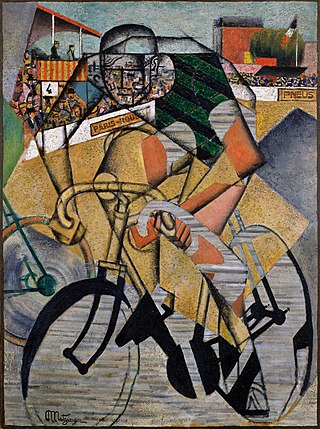

Au Vélodrome, also known as At the Cycle-Race Track and Le cycliste, is a painting by the French artist and theorist Jean Metzinger. The work illustrates the final meters of the Paris–Roubaix race, and portrays its 1912 winner Charles Crupelandt. Metzinger's painting is the first in Modernist art to represent a specific sporting event and its champion.

The Société Normande de Peinture Moderne, also known as Société de Peinture Moderne, or alternatively, Normand Society of Modern Painting, was a collective of eminent painters, sculptors, poets, musicians and critics associated with Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism and Orphism. The Société Normande de la Peinture Moderne was a diverse collection of avant-garde artists; in part a subgrouping of the Cubist movement, evolving alongside the so-called Salon Cubist group, first independently then in tandem with the core group of Cubists that emerged at the Salon d'Automne and Salon des Indépendants between 1909 and 1911. Historically, the two groups merged in 1912, at the Section d'Or exhibition, but documents from the period prior to 1912 indicate the merging occurred earlier and in a more convoluted manner.

Woman with a Fan is an oil painting created in 1912 by the French artist and theorist Jean Metzinger (1883–1956). The painting was exhibited at the Salon d'Automne, 1912, Paris, and De Moderne Kunstkring, 1912, Amsterdam. It was also exhibited at the Musée Rath, Geneva, Exposition de cubistes français et d'un groupe d'artistes indépendants, 3–15 June 1913. A 1912 photograph of Femme à l'Éventail hanging on a wall inside the Salon Bourgeois was published in The Sun, 10 November 1912. The same photograph was reproduced in The Literary Digest, 30 November 1912.

Man with Pipe is a Cubist painting by the French artist Jean Metzinger. It has been suggested that the sitter depicted in the painting represents either Guillaume Apollinaire or Max Jacob. The work was exhibited in the spring of 1914 at the Salon des Indépendants, Paris, Champ-de-Mars, March 1–April 30, 1914, no. 2289, Room 11. A photograph of Le Fumeur was published in Le Petit Comtois, 13 March 1914, for the occasion of the exhibition. In July 1914 the painting was exhibited in Berlin at Herwarth Walden’s Galerie Der Sturm, with works by Albert Gleizes, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon.

Lady with a her Dressing Table is a painting by the French artist Jean Metzinger. This distilled synthetic form of Cubism exemplifies Metzinger's continued interest, in 1916, towards less surface activity, with a strong emphasis on larger, flatter, overlapping abstract planes. The manifest primacy of the underlying geometric configuration, rooted in the abstract, controls nearly every element of the composition. The role of color remains primordial, but is now restrained within sharp delineated boundaries in comparison with several earlier works. The work of Juan Gris from the summer of 1916 to late 1918 bears much in common with that of Metzinger's late 1915 – early 1916 paintings.

Portrait of an Army Doctor is an oil-on-canvas painting created during 1914–15 by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes. Painted at the fortress city of Toul (Lorraine) while Gleizes served in the military during the First World War, the painting's abstract circular rhythms and intersecting aslant planes announce the beginning of the second synthetic phase of Cubism. The work represents Gleizes's commanding officer, Major Mayer-Simon Lambert (1870–1943), the regimental surgeon in charge of the military hospital at Toul. At least eight preparatory sketches, gouaches and watercolors of the work have survived, though Portrait of an Army Doctor is one of Gleizes's only major oil paintings of the period.

La Maison Cubiste, also called Projet d'hôtel, was an architectural installation in the Art Décoratif section of the 1912 Paris Salon d'Automne which presented a Cubist vision of architecture and design. Critics and collectors present at the exhibition were confronted for the first time with the prospect of a Cubist architecture.

Composition for "Jazz", or Composition , is a 1915 painting by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes. This Cubist work was reproduced in a photograph of Gleizes working on the painting in the Xeic York Herald, then published in The Literary Digest, 27 November 1915 (p. 1225). Composition for "Jazz" was purchased in 1938 by Solomon R. Guggenheim from Feragil Gallery, New York and forms part of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection. The painting is in the permanent collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City.