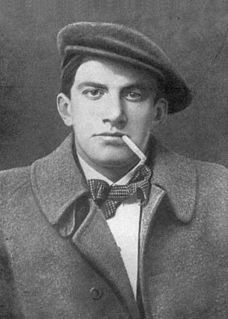

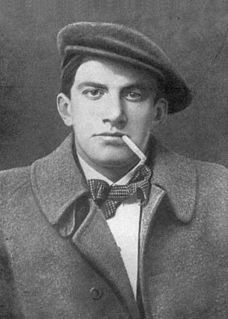

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky was a Russian and Soviet poet, playwright, artist, and actor.

Futurism was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy in the early 20th century which later also developed in Russia. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. Its key figures were the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. It glorified modernity and aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its past. Important Futurist works included Marinetti's Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni's sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla's painting Abstract Speed + Sound, and Russolo's The Art of Noises.

Rayonism was a style of abstract art that developed in Russia in 1910–1914. Founded and named by Russian Cubo-Futurists Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, it was one of Russia's first abstract art movements.

Vasily Ivanovich Gnedov, better known by the pen name Vasilisk Gnedov, was one of the most radically experimental poets of Russian Futurism, though not as prolific as his peers.

Aleksei Yeliseyevich Kruchyonykh was a Russian poet, artist, and theorist, perhaps one of the most radical poets of Russian Futurism, a movement that included Vladimir Mayakovsky, David Burliuk and others. Born in 1886, he lived in the time of the Russian Silver Age of literature, and together with Velimir Khlebnikov, another Russian Futurist, Kruchenykh is considered the inventor of zaum, a poetry style utilising nonsense words. Kruchonykh wrote the libretto for the Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun, with sets provided by Kazimir Malevich. In 1912, he wrote the poem Dyr bul shchyl; four years later, in 1916, he created his most famous book, Universal War.

The Russian avant-garde was a large, influential wave of avant-garde modern art that flourished in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, approximately from 1890 to 1930—although some have placed its beginning as early as 1850 and its end as late as 1960. The term covers many separate, but inextricably related, art movements that flourished at the time; including Suprematism, Constructivism, Russian Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Zaum and Neo-primitivism. Many of the artists who were born, grew up or were active in what is now Belarus and Ukraine, are also classified in the Ukrainian avant-garde.

Cubo-Futurism was an art movement that arose in early 20th century Russia, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo-Futurism was the main school of painting and sculpture practiced by the Russian Futurists. In 1913, the term ‘Cubo-Futurism’ first came to describe works from members of the poetry group ‘Hylaeans,’ as they moved away from poetic Symbolism towards Futurism and zaum, the experimental “visual and sound poetry of Kruchenykh and Khlebninkov”. Later in the same year the concept and style of ‘Cubo-Futurism’ became synonymous with the works of artists within Russian post-revolutionary avant-garde circles as they interrogated non-representational art through the fragmentation and displacement of traditional forms, lines, viewpoints, colours, and textures within their pieces. The impact of Cubo-Futurism was then felt within performance art societies, with Cubo-Futurist painters and poets collaborating on theatre, cinema, and ballet pieces that aimed to break theatre conventions through the use of nonsensical zaum poetry, emphasis on improvisation, and the encouragement of audience participation.

Imaginism was a Russian avant-garde poetic movement that began after the Revolution of 1917.

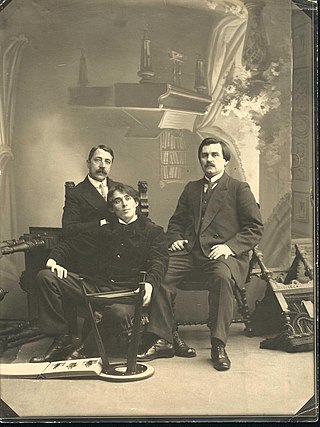

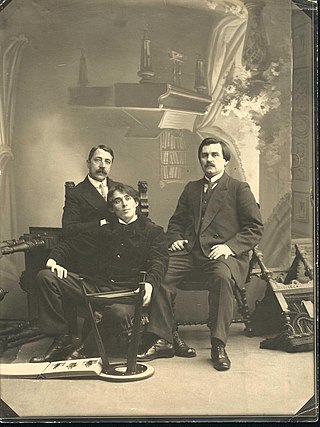

David Davidovich Burliuk was a Russian-language poet, artist, publicist and book illustrator associated with the Futurist, Neo-Primitivist and Futurism movements. Burliuk is often described as "the father of Russian Futurism".

Rurik Ivnev, born Mikhail Alexandrovich Kovalyov, was a Russian poet, novelist and translator.

Vadim Gabrielevich Shershenevich (1893–1942) was a Russian poet. He was highly prolific, working in more than one genre, moving from Symbolism to Futurism after meeting Marinetti in Moscow. Later he pioneered the post-revolutionary avant-garde Imaginist movement, but abandoned it in favour of the theatre.

Russian Futurism is the broad term for a movement of Russian poets and artists who adopted the principles of Filippo Marinetti's "Manifesto of Futurism," which espoused the rejection of the past, and a celebration of speed, machinery, violence, youth, industry, destruction of academies, museums, and urbanism; it also advocated the modernization and cultural rejuvenation.

Benedikt Konstantinovich Livshits was a poet and writer of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry, a French–Russian poetry translator.

Futurism is a modernist avant-garde movement in literature and part of the Futurism art movement that originated in Italy in the early 20th century. It made its official literature debut with the publication of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's Manifesto of Futurism (1909). Futurist poetry is characterised by unexpected combinations of images and by its hyper-concision. Futurist theatre also played an important role within the movement and is distinguished by scenes that are only a few sentences long, an emphasis on nonsensical humour, and attempts to examine and subvert traditions of theatre via parody and other techniques. Longer forms of literature, such as the novel, have no place in the Futurist aesthetic of speed and compression. Futurist literature primarily focuses on seven aspects: intuition, analogy, irony, abolition of syntax, metrical reform, onomatopoeia, and essential/synthetic lyricism.

Universal War is an artist's book by Aleksei Kruchenykh published in Petrograd at the beginning of 1916. Despite being produced in an edition of 100 of which only 12 are known to survive, the book has become one of the most famous examples of Russian Futurist book production, and is considered a seminal example of avant-garde art from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Tango With Cows: Ferro-Concrete Poems is an artists' book by the Russian Futurist poet Vasily Kamensky, with additional illustrations by the brothers David and Vladimir Burliuk. Printed in Moscow in 1914 in an edition of 300, the work has become famous primarily for being made entirely of commercially produced wallpaper, with a series of concrete poems - visual poems that employ unusual typographic layouts for expressive effect - printed onto the recto of each page.

Graal-Arelsky or Stepan Stephanovich Petrov, was a poet of Ego-Futurism in Russia. He co-founded the Academy of Ego-Poetry with fellow Ego-Futurist Konstantin Olimpov. Arelsky is also an identified astronomer.

Konstantin Konstantinovich Olimpov (1889–1940) Birth name Konstantin Konstantinovich Fofanov

Pavel Dmitrievich Shirokov (1893–1963) was a poet of Ego-Futurism in Russia in the 1910s. He was a close friend of Ivan Ignatyev, who published Shirokov's first book entitled "Rozy v Vine". Neologisms and French words occur frequently in Shirokov's works; he refers to his verses using French terms such as triolets, virelais, romances, etc., a characteristic possibly derived from fellow Ego-Futurist Igor Severyanin. In January 1913 another book of poems was published, entitled "V i Vne", described by critic Vladimir Markov as "much less successful and, strangely enough, less futuristic." Pavel Shirokov later participated in publications of the Moscow Futurists, though never published any more books, and faded into obscurity.

Boris Anisimovich Kušner (1888–1937) was a Russian poet, critic and political activist. He was a publicist for the Cubo-Futurists: In 1917 he wrote a manifesto, "Democratic Art", which called for a guarantee for all art movements to have a right to exist and the creation of an environment whereby fresh forces and views would be encouraged so that all works of art would be available to all people.