Futurism was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. Its key figures included Italian artists Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. Italian Futurism glorified modernity and, according to its doctrine, "aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its past." Important Futurist works included Marinetti's 1909 Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni's 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla's 1913–1914 painting Abstract Speed + Sound, and Russolo's The Art of Noises (1913).

Umberto Boccioni was an influential Italian painter and sculptor. He helped shape the revolutionary aesthetic of the Futurism movement as one of its principal figures. Despite his short life, his approach to the dynamism of form and the deconstruction of solid mass guided artists long after his death. His works are held by many public art museums, and in 1988 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City organized a major retrospective of 100 pieces.

Giacomo Balla was an Italian painter, art teacher and poet best known as a key proponent of Futurism. In his paintings, he depicted light, movement and speed. He was concerned with expressing movement in his works, but unlike other leading futurists he was not interested in machines or violence with his works tending towards the witty and whimsical.

Rayonism was a style of abstract art that developed in Russia in 1910–1914. Founded and named by Russian Cubo-Futurists Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, it was one of Russia's first abstract art movements.

Lyubov Sergeyevna Popova was a Russian-Soviet avant-garde artist, painter and designer.

The Russian avant-garde was a large, influential wave of avant-garde modern art that flourished in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, approximately from 1890 to 1930—although some have placed its beginning as early as 1850 and its end as late as 1960. The term covers many separate, but inextricably related, art movements that flourished at the time; including Suprematism, Constructivism, Russian Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Zaum, Imaginism, and Neo-primitivism. In Ukraine, many of the artists who were born, grew up or were active in what is now Belarus and Ukraine, are also classified in the Ukrainian avant-garde.

Natalia Sergeevna Goncharova was a Russian avant-garde artist, painter, costume designer, writer, illustrator, and set designer. Goncharova's lifelong partner was fellow Russian avant-garde artist Mikhail Larionov. She was a founding member of both the Jack of Diamonds (1909–1911), Moscow's first radical independent exhibiting group, the more radical Donkey's Tail (1912–1913), and with Larionov invented Rayonism (1912–1914). She was also a member of the German-based art movement Der Blaue Reiter. Born in Russia, she moved to Paris in 1921 and lived there until her death.

Cubo-Futurism or Kubo-Futurizm was an art movement, developed within Russian Futurism, that arose in early 20th century Russian Empire, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo-Futurism was the main school of painting and sculpture practiced by the Russian Futurists. In 1913, the term "Cubo-Futurism" first came to describe works from members of the poetry group "Hylaeans", as they moved away from poetic Symbolism towards Futurism and zaum, the experimental "visual and sound poetry of Kruchenykh and Khlebninkov". Later in the same year the concept and style of "Cubo-Futurism" became synonymous with the works of artists within Ukrainian and Russian post-revolutionary avant-garde circles as they interrogated non-representational art through the fragmentation and displacement of traditional forms, lines, viewpoints, colours, and textures within their pieces. The impact of Cubo-Futurism was then felt within performance art societies, with Cubo-Futurist painters and poets collaborating on theatre, cinema, and ballet pieces that aimed to break theatre conventions through the use of nonsensical zaum poetry, emphasis on improvisation, and the encouragement of audience participation.

Mikhail Fyodorovich Larionov was a Russian avant-garde painter who worked with radical exhibitors and pioneered the first approach to abstract Russian art. His lifelong partner was fellow avant-garde artist, Natalia Goncharova.

Donkey's Tail was a Russian artistic group created from the most radical members of the Jack of Diamonds group. The group included such painters as: Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Kazimir Malevich, Marc Chagall, and Aleksandr Shevchenko. The group, according to Gino Severini in his autobiography, was Futurist; it is known that, even if they were not, they were certainly influenced by the Cubo-Futurism movement. The only exhibition of the group took place in Moscow in 1912, and in 1913, the group fell apart.

Olga Vladimirovna Rozanova was a Russian avant-garde artist painting in the styles of Suprematism, Neo-Primitivism, and Cubo-Futurism.

Nadezhda Andreevna Udaltsova was a Russian avant-garde artist, painter and teacher.

Russian Futurism is the broad term for a movement of Russian poets and artists who adopted the principles of Filippo Marinetti's "Manifesto of Futurism", which espoused the rejection of the past, and a celebration of speed, machinery, violence, youth, industry, destruction of academies, museums, and urbanism; it also advocated for modernization and cultural rejuvenation.

Universal War is an artist's book by Aleksei Kruchenykh published in Petrograd at the beginning of 1916. Despite being produced in an edition of 100 of which only 12 are known to survive, the book has become one of the most famous examples of Russian Futurist book production, and is considered a seminal example of avant-garde art from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Tango With Cows: Ferro-Concrete Poems is an artists' book by the Russian Futurist poet Vasily Kamensky, with additional illustrations by the brothers David and Vladimir Burliuk. Printed in Moscow in 1914 in an edition of 300, the work has become famous primarily for being made entirely of commercially produced wallpaper, with a series of concrete poems - visual poems that employ unusual typographic layouts for expressive effect - printed onto the recto of each page.

The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 was an exhibition presented by the Dobychina Art Bureau at Marsovo Pole, Petrograd, from 19 December 1915 to 17 January 1916. The exhibition was important in inaugurating a form of non-objective art called Suprematism, introducing a daring visual vernacular composed of geometric forms of varying colour, and in signifying the end of Russia's previous leading art movement, Cubo-Futurism, hence the exhibition's full name. The sort of geometric abstraction relating to Suprematism was distinct in the apparent kinetic motion and angular shapes of its elements.

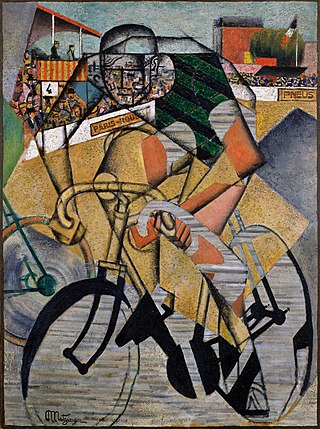

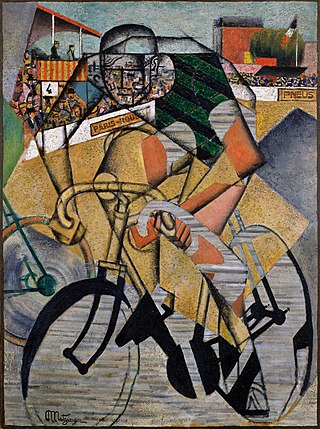

Au Vélodrome, also known as At the Cycle-Race Track and Le cycliste, is a painting by the French artist and theorist Jean Metzinger. The work illustrates the final meters of the Paris–Roubaix race, and portrays its 1912 winner Charles Crupelandt. Metzinger's painting is the first in Modernist art to represent a specific sporting event and its champion.

Dynamism of a Cyclist is a 1913 oil painting by Italian Futurist artist Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916) that demonstrates the Futurist fascination with speed, modern methods of transport, and the depiction of the dynamic sensation of movement.

Růžena Zátková, also called Rougina Zatkova, was a painter and sculptor who has been regarded as the "only authentic Czech futurist." As a result of her Bohemian heritage and her decade-long residency in Rome, Růžena Zátková became an important artistic link between Russian and Italian Futurism. Zátková is considered one of the pioneers of kinetic art.

An Englishman in Moscow, is a 1914 oil on canvas painting by Russian avant-garde artist and art theorist Kazimir Malevich.