Academic career

Terence Ingold was born at Blackrock, Dublin and attended school in Bangor, County Down. [4] He studied at Queen's University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and in 1926 won a First in his bachelor's degree in Biology and botany, with emphasis on mycology. He made a short study (in the style of A.H.R. Buller) of dispersal patterns of a Podospora species before taking up a scholarship in autumn 1926 at the Royal College of Science, London. Here the teaching and practicals in higher plant physiology by V. H. Blackman and others stimulated and laid a pattern for his later experimental thinking. He awoke to the value of scientific excursions (which became a keynote of his own teaching) through geological forays at Belfast led by J.K. Charlesworth, and taking part in Sir John Farmer's investigation of mountain vegetation in Snowdonia. [5]

In 1927, the year in which he was elected to the Linnean Society of London, [6] he returned to Queen's University for his doctorate in botany which he was awarded in 1930. His dissertation was on systems in plant sap that buffer against changes in pH. During this time he also mapped the vegetation of the summit of Slieve Donard: in 1934 the project was extended, with collaborators, to map the vegetation of the Mourne Mountains as a whole.

University of Reading

In 1929 Dr. Ingold received a faculty lectureship in the Department of Botany, then led by Professor J.R. Matthews, at the University of Reading. In 1934 the palaeobotanist T.M. Harris succeeded to the chair, and greatly influenced him by the example of his energy, his immense knowledge of plants in their environment and in laboratory, and his clarity and honesty of intellect. [5] In 1932, at the urging of Walter Buddin, Ingold joined the British Mycological Society. [3]

University of Leicester

Involvement with the Society strengthened Dr. Ingold's interests in the Fungi. They had become fully confirmed when, in 1937, he was appointed Lecturer in Charge of the Department of Botany at the University College of Leicester. Harris's constant encouragement and guidance were acknowledged in his book Spore Discharge in Land Plants, then in preparation. [7] Ingold took the opportunity to clear away the preserved specimens and to teach from living plants. The analytic and instructive clarity of his line-drawings from the microscope were a hallmark of his research and teaching. The Leicestershire waters and waterways and their aquatic fungi became a focus of interest studied by a circle of his research students, especially in relation to chytridiaceous parasites of freshwater algae (in which his student Hilda Canter (Lund) became expert [6] ), and to aquatic Hyphomycetes. In 1942 he published his seminal work: "Aquatic hyphomycetes of decaying alder leaves". [8]

Birkbeck College, University of London

The researches so commenced, and his own particular interest in the hyphomycetes, were continued by Ingold and his students over many years. In 1944 he was appointed to probably the foremost chair in United Kingdom in the field of mycology, at Birkbeck College, University of London. [1] The Department of Botany had been led to prominence since 1909 by Dame Helen Gwynne-Vaughan, pioneer in fungal genetics, who was made Professor in 1921. Following her retirement as Professor Emeritus Ingold first had the task of maintaining its work in the bomb-damaged premises at Fetter Lane during the last months of the War. [6] After the cessation of hostilities he was able to oversee its redevelopment and subsequent move in 1952 to the new Birkbeck College in Malet Street. [5]

At Birkbeck Professor Ingold continued to take a major role in the undergraduate teaching, and was joined in 1946 by his wartime Leicester student Bryan Plunkett [9] as lecturer, who remained with him permanently thereafter. Lectures were customarily illustrated by multiple living cultures prepared in laboratory for use with microscopes. Emphasis on fieldwork, living organisms and plants in their environment was maintained by frequent forays with students to favoured locations. In 1965, with a departmental academic staff of seven, he observed that the increasing need to present Botany as an experimental subject would in future demand greatly enlarged facilities, which might only be achieved by the reorganisation of their work, with other biological colleagues, into a School of Life Sciences. [10] Meanwhile, the Zoological and Botanical departments alternately led the annual expeditions or field trips with students and colleagues for the study of marine environments, for example to Dale Fort near Haverfordwest, Port Erin (Isle of Man), St Peter Port (Guernsey) and to the Scilly Isles.

An MSc course in mycology was developed, [4] and much productive research was undertaken, both into aquatic ascomycetes and hyphomycetes, and in studies of the processes of spore production, release and dispersal. The book Dispersal in fungi (1953) described and emphasised dispersal as a vital problem in the life of fungi. [11] Spore Liberation (1965), not a revision of the former, summarised fields of recent research to reveal how spore liberation was fundamental to understanding the structure of fungal fruiting bodies and bryophyte sporogonia. [12] A full revision combining both works in the light of much further research appeared as Fungal Spores, Their Liberation and Dispersal in 1971. [13] His textbook The Biology of Fungi, for those commencing formal study of fungi, was first published in 1961 and was fully revised in later editions. [14] Professor Ingold retired from post at Birkbeck in 1972, and was succeeded as Professor by the palaeo-botanist W.G. Chaloner.

Service to scientific and educational bodies

In the University of London Professor Ingold was Dean of the Faculty of Science (1956–60), Chairman of the University Entrance and School's Examination Council (1958–64), Deputy Vice-Chancellor (1966–68), and Chairman of the Academic Council (1969–72). He served as Vice-Master of Birkbeck College from 1965 to 1970. He was a member of the Inter-Universities' Council for Higher Education Overseas, and its vice-chairman 1969–74. He made special efforts towards the development of the University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. [5] He assisted in setting up the New University of Ulster (Coleraine) and the University of Kent (Canterbury). [4]

Having served on the Council of the Linnean Society from 1955 to 1957, Professor Ingold was its Botanical Secretary from 1962 to 1997, was Vice-President in 1954–55 and 1965–66, and was a gold medallist in 1983. He was twice President of the British Mycological Society (1953 and 1971), and was President of the First International Congress of Mycology at Exeter in 1971. He was also Chairman of the Council of the Freshwater Biological Association 1965–74. [5] He continued to work on fungi for thirty years after his retirement. [1] By 1985, at the age of 80, he had produced 174 scientific publications; [15] and approximately 100 appeared after that date. [6]

His daughter is Patsy Healey [16] and son is the noted anthropologist Tim Ingold. [17]

A basidium is a microscopic spore-producing structure found on the hymenophore of reproductive bodies of basidiomycete fungi. The presence of basidia is one of the main characteristic features of the group. These bodies also called tertiary mycelia, which are highly coiled versions of secondary mycelia. A basidium usually bears four sexual spores called basidiospores. Occasionally the number may be two or even eight. Each reproductive spore is produced at the tip of a narrow prong or horn called a sterigma (pl. sterigmata), and is forcefully expelled at full growth.

Edred John Henry Corner FRS was an English mycologist and botanist who occupied the posts of assistant director at the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1929–1946) and Professor of Tropical Botany at the University of Cambridge (1965–1973). Corner was a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College from 1959.

The British Mycological Society is a learned society established in 1896 to promote the study of fungi.

Pier Andrea Saccardo was an Italian botanist and mycologist. He was also the author of a color classification system that he called Chromotaxia. He was elected to the Linnean Society in 1916 as a foreign member. His multi-volume Sylloge Fungorum was one of the first attempts to produce a comprehensive treatise on the fungi which made use of the spore-bearing structures for classification.

Christopher Edmund Broome was a British mycologist. The standard author abbreviation Broome is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

Douglas Barton Osborne Savile was an Irish-born Canadian mycologist, plant pathologist and evolutionary biologist. He is particularly renowned for his unique work on the coevolution of host plants and their rust fungi.

Michael Francis Madelin (1931–2007) was a British mycologist. He held research faculty positions at Imperial College, University of London, and the University of Bristol, and undertook pioneering research in conidial fungi and slime moulds, with specific reference to their physiology and ecology.

The fungi imperfecti or imperfect fungi are fungi which do not fit into the commonly established taxonomic classifications of fungi that are based on biological species concepts or morphological characteristics of sexual structures because their sexual form of reproduction has never been observed. They are known as imperfect fungi because only their asexual and vegetative phases are known. They have asexual form of reproduction, meaning that these fungi produce their spores asexually, in the process called sporogenesis.

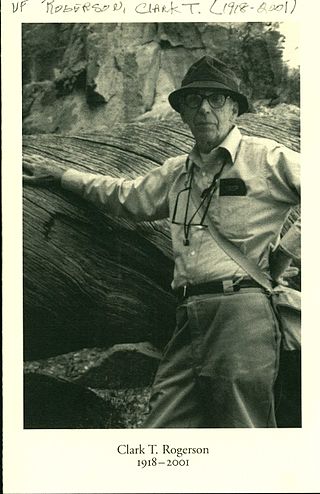

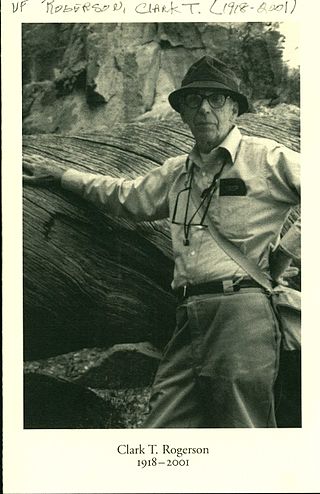

Clark Thomas Rogerson,, was an American mycologist. He was known for his work in the Hypocreales (Ascomycota), particularly Hypomyces, a genus of fungi that parasitize other fungi. After receiving his doctorate from Cornell University in 1950, he went on to join the faculty of Kansas State University. In 1958, he became a curator at The New York Botanical Garden, and served as editor for various academic journals published by the Garden. Rogerson was involved with the Mycological Society of America, serving in various positions, including president in 1969. He was managing editor (1958–89) and editor-in-chief (1960–65) of the scientific journal Mycologia.

Charles Frank Drechsler was an American mycologist with 45 years of research with the United States Department of Agriculture. He spent considerable time working with cereal fungal diseases, and the genus Drechslera was named after him. Drechsler also worked extensively on oomycete fungi and their interactions with vegetable plants. Drechsler was recognized as a leading authority on helminthosporia, oomycetes, and other parasitic fungi.

William Henry Weston Jr. (1890–1978) was an American botanist, mycologist, and first president of the Mycological Society of America. Weston was known for his research in the fungal group known as the phycomycetes, particularly the pathogenic genus Sclerospora.

Robert Francis Ross McNabb was a New Zealand mycologist. He was born in Kawakawa, and attended local schools in his youth, including Whangarei Boys' High School and Southland Boys' High School. He received a BSc degree from the University of Otago in 1956, and two years later an MSc for his work on mycorrhizae morphology in native New Zealand plants. In 1961, having been awarded a National Research Fellowship the year before, McNabb left New Zealand for the UK to study with Cecil Terence Ingold at Birkbeck College. McNabb earned a PhD in 1963; his thesis was titled "Taxonomic studies in the Dacrymycetaceae". He was jointly awarded the Hamilton Memorial Prize in 1966 from The Royal Society of New Zealand, the same year he was appointed to the editorial board of the New Zealand Journal of Botany. Most of McNabb's later publications, largely published in this journal, were about fungal taxonomy. Fungus species named in honor of McNabb include Paxillus mcnabbii, and Entoloma mcnabbianum.

John Webster was an internationally renowned mycologist and head of biological sciences at the University of Exeter in England. He also served twice as president of the British Mycological Society. He is recognised for determining the physiological mechanism underpinning fungal spore release, though is probably best known by students of mycology for his influential textbook, Introduction to Fungi.

Chirayathumadom Venkatachalier Subramanian, popularly known as CVS, was an Indian mycologist, taxonomist and plant pathologist, known for his work on the classification of Fungi imperfecti, a group of fungi classified separately due to lack of specific taxonomic characteristics. He authored one monograph, Hyphomycetes: An Account of Indian Species, Except Cercosporae and three books, Hyphomycetes, taxonomy and biology, Moulds, Mushrooms and Men and Soil microfungi of Israel, besides several articles published in peer-reviewed journals. He was a recipient of many honours including the Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Award of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, the Janaki Ammal National Award of the Government of India and seven species of fungi have been named after him. The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, the apex agency of the Government of India for scientific research, awarded him the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize for Science and Technology, one of the highest Indian science awards, in 1965, for his contributions to biological sciences.

Lilian Edith Hawker was a British mycologist, known for her work on fungal physiology, particularly spore production. She was an expert on British truffles, and also published in the fields of plant physiology and plant pathology. She was also known for her contributions to education in mycology. Most of her career was spent at the botany department of the Imperial College of Science and Technology (1932–45) and the University of Bristol (1945–73), where she held the chair in mycology (1965–73) and was dean of the science faculty (1970–73). She served as president of the British Mycological Society, and was elected an honorary member of that society and of the Mycological Society of America. She published an introduction to fungi and two books on fungal physiology, of which Physiology of Fungi (1950) was among the first to survey the field, and also co-edited two microbiology textbooks.

Anguillospora is a genus of fungi belonging to the family Amniculicolaceae. It was circumscribed by Cecil Terence Ingold in 1942, with Anguillospora longissima assigned as the type species. It was found as a root endophytic fungus in the plant Equisetum scirpoides. It is related to the genera Amniculicola and Lophiostoma. The genus has a cosmopolitan distribution.

Stanley John Hughes (1918–2019) was a Canadian scientist who is known throughout the global field of mycology for developing and introducing a precise and meticulous system for classifying fungi that is still used today. A naturalized Canadian, he was a federal research scientist for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at what is today the Ottawa Research and Development Centre.

Guy Richard Bisby (1889–1958) was an American Canadian mycologist and botanist in plant pathology. He spent his early career working as a professor at the University of Minnesota and University of Manitoba in plant pathology, and his late career as Senior Assistant Mycologist at the Imperial Mycological Institute in Kew, England. He published around fifty books and papers in mycology that extensively contributed to the taxonomy and nomenclature of fungi.

Keisuke Tubaki was a Japanese mycologist.

Philip Herries Gregory was a British mycologist and phytopathologist. He established an international reputation as a pioneer of aerobiology and a leading expert on the liberation and dispersal of fungal spores and their relation to plant diseases and to human respiratory diseases. In 1957 he was elected to a one-year term as president of the British Mycological Society.