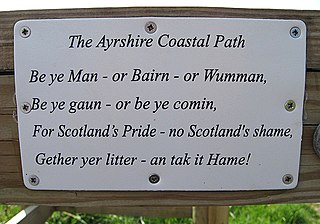

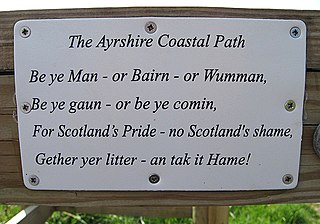

Doric, the popular name for Mid Northern Scots or Northeast Scots, refers to the Scots language as spoken in the northeast of Scotland. There is an extensive body of literature, mostly poetry, ballads, and songs, written in Doric. In some literary works, Doric is used as the language of conversation while the rest of the work is in Lallans Scots or British English. A number of 20th and 21st century poets have written poetry in the Doric dialect.

Scots is an Anglic language variety in the West Germanic language family, spoken in Scotland and parts of Ulster in the north of Ireland. Most commonly spoken in the Scottish Lowlands, Northern Isles, and northern Ulster, it is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Goidelic Celtic language that was historically restricted to most of the Scottish Highlands, the Hebrides, and Galloway after the sixteenth century; or Broad Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Standard English. Modern Scots is a sister language of Modern English, as the two diverged independently from the same source: Early Middle English (1150–1350).

Lothian is a region of the Scottish Lowlands, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills and the Moorfoot Hills. The principal settlement is the Scottish capital, Edinburgh, while other significant towns include Livingston, Linlithgow, Bathgate, Queensferry, Dalkeith, Bonnyrigg, Penicuik, Musselburgh, Prestonpans, Tranent, North Berwick, Dunbar, Whitburn and Haddington.

Ulster Scots or Ulster-Scots, also known as Ulster Scotch and Ullans, is the dialect spoken in parts of Ulster, being almost exclusively spoken in parts of Northern Ireland and County Donegal. It is normally considered a dialect or group of dialects of Scots, although groups such as the Ulster-Scots Language Society and Ulster-Scots Academy consider it a language in its own right, and the Ulster-Scots Agency and former Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure have used the term Ulster-Scots language.

Scottish English is the set of varieties of the English language spoken in Scotland. The transregional, standardised variety is called Scottish Standard English or Standard Scottish English (SSE). Scottish Standard English may be defined as "the characteristic speech of the professional class [in Scotland] and the accepted norm in schools". IETF language tag for "Scottish Standard English" is en-scotland.

The history of the Scots language refers to how Anglic varieties spoken in parts of Scotland developed into modern Scots.

The voiceless labial–velar fricative is a type of consonantal sound, used in spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨xʷ⟩ or occasionally ⟨ʍ⟩. The letter ⟨ʍ⟩ was defined as a "voiceless " until 1979, when it was defined as a fricative with the place of articulation of the same way that is an approximant with the place of articulation of. The IPA Handbook describes ⟨ʍ⟩ as a "fricative" in the introduction while a chapter within characterizes it as an "approximate".

A farl is any of various quadrant-shaped flatbreads and cakes, traditionally made by cutting a round into four pieces. In Ulster, the term generally refers to soda bread and, less commonly, potato bread, which are also ingredients of an Ulster fry.

Highland English is the variety of Scottish English spoken by many in Gaelic-speaking areas and the Hebrides. It is more strongly influenced by Gaelic than are other forms of Scottish English.

Ulster English, also called Northern Hiberno-English or Northern Irish English, is the variety of English spoken mostly around the Irish province of Ulster and throughout Northern Ireland. The dialect has been influenced by the local Ulster dialect of the Scots language, brought over by Scottish settlers during the Plantation of Ulster and subsequent settlements throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. It also coexists alongside the Ulster dialect of the Irish (Gaelic) language.

The spoken English language in Northern England has been shaped by the region's history of settlement and migration, and today encompasses a group of related accents and dialects known as Northern England English or Northern English.

The cot–caught merger, also known as the LOT–THOUGHT merger or low back merger, is a sound change present in some dialects of English where speakers do not distinguish the vowel phonemes in words like cot versus caught. Cot and caught is an example of a minimal pair that is lost as a result of this sound change. The phonemes involved in the cot–caught merger, the low back vowels, are typically represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet as and or, in North America, as and. The merger is typical of most Indian, Canadian, and Scottish English dialects as well as some Irish and U.S. English dialects.

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtually indistinguishable from early Northumbrian Middle English. Subsequently, the orthography of Middle Scots differed from that of the emerging Early Modern English standard that was being used in England. Middle Scots was fairly uniform throughout its many texts, albeit with some variation due to the use of Romance forms in translations from Latin or French, turns of phrases and grammar in recensions of southern texts influenced by southern forms, misunderstandings and mistakes made by foreign printers.

The Scottish vowel length rule describes how vowel length in Scots, Scottish English, and, to some extent, Ulster English and Geordie is conditioned by the phonetic environment of the target vowel. Primarily, the rule is that certain vowels are phonetically long in the following environments:

Australian English is relatively homogeneous when compared with British and American English. The major varieties of Australian English are sociocultural rather than regional. They are divided into 3 main categories: general, broad and cultivated.

The 'apologetic' or parochial apostrophe is the distinctive use of apostrophes in some Modern Scots spelling. Apologetic apostrophes generally occurred where a consonant exists in the Standard English cognate, as in a' (all), gi'e (give) and wi' (with).

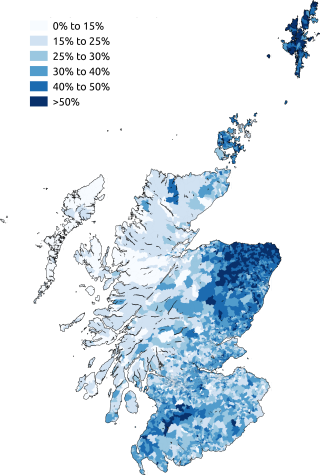

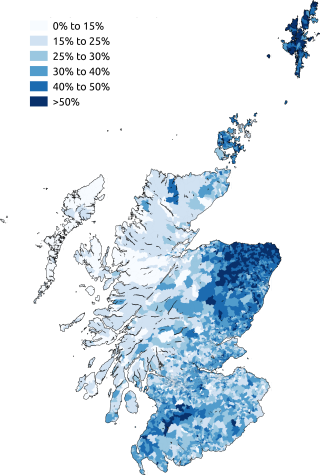

Shetland dialect is a dialect of Insular Scots spoken in Shetland, an archipelago to the north of mainland Scotland. It is derived from the Scots dialects brought to Shetland from the end of the fifteenth century by Lowland Scots, mainly from Fife and Lothian, with a degree of Norse influence from the Norn language, which is an extinct North Germanic language spoken on the islands until the late 18th century.

Southern Scots is the dialect of Scots spoken in the Scottish Borders counties of mid and east Dumfriesshire, Roxburghshire and Selkirkshire, with the notable exception of Berwickshire and Peeblesshire, which are, like Edinburgh, part of the SE Central Scots dialect area. It may also be known as Border Scots, the Border tongue or by the names of the towns inside the South Scots area, for example Teri in Hawick from the phrase Teribus ye teri odin. Towns where Southern Scots dialects are spoken include Earlston, Galashiels, Hawick, Jedburgh, Kelso, Langholm, Lockerbie, Newcastleton, St. Boswells and Selkirk.

Modern Scots comprises the varieties of Scots traditionally spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster, from 1700.

North Northern Scots is a group of Scots dialects spoken in Caithness, the Black Isle and Easter Ross.