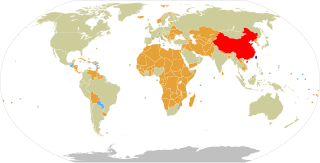

The Republic of China (ROC), often known informally as Taiwan, currently has formal diplomatic relations with 12 of the 193 United Nations member states and with the Holy See, which governs Vatican City, as of 24 June 2023. In addition to these relations, the ROC also maintains unofficial relations with 59 UN member states, one self-declared state (Somaliland), three territories (Guam, Hong Kong, and Macau), and the European Union via its representative offices and consulates under the One China principle. The Government of the Republic of China has the 31st largest diplomatic network in the world with 110 offices.

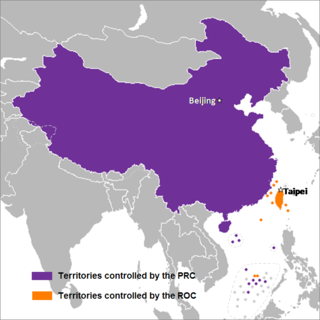

Chinese unification, also known as the Cross-Strait unification or Chinese reunification, is the potential unification of territories currently controlled, or claimed, by the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China ("Taiwan") under one political entity, possibly the formation of a political union between the two republics. Together with full Taiwan independence, unification is one of the main proposals to address questions on the political status of Taiwan, which is a central focus of Cross-Strait relations.

The Taiwan Relations Act is an act of the United States Congress. Since the formal recognition of the People's Republic of China, the Act has defined the officially substantial but non-diplomatic relations between the US and Taiwan.

The controversy surrounding the political status of Taiwan or the Taiwan issue is a result of World War II, the second phase of the Chinese Civil War (1945–1949), and the Cold War.

The term One China may refer to one of the following:

The relationship between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the United States of America (U.S.) has been complex since the establishment of the PRC and the retreat of the government of the Republic of China (ROC) to Taiwan in 1949. They have close economic ties and are significantly intertwined, yet they also have a hegemonic great power rivalry throughout the Asia-Pacific and beyond. While both countries have mutual political, economic, and security interests, there are also unresolved concerns, with differentiating views such as on the political status of Taiwan or territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Both countries are economic juggernauts – China and the United States are respectively the world's second and first-largest economies by nominal GDP and the first and second-largest economies by GDP PPP; collectively they make up 44.2% of the world GDP by nominal and 34.7% by PPP.

The status of permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) is a legal designation in the United States for free trade with a foreign nation. The designation was changed from most favored nation (MFN) to normal trade relations by Section 5003 of the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998. Permanent was added to normal trade relations some time later.

The Blue Team is an informal term for a group of politicians and journalists in United States loosely unified by their belief that the People's Republic of China is a significant security threat to the United States. Though allied on some issues with Democratic advocates of labor, most of those to whom the term has been applied are conservative or neoconservative. However, few occupied positions of high power within the Bush administration, instead tending to work for the Pentagon, the US Intelligence Community, private think tanks, and media outlets.

The Six Assurances are six key foreign policy principles of the United States regarding United States–Taiwan relations. They were passed as unilateral U.S. clarifications to the Third Communiqué between the United States and the People's Republic of China in 1982. They were intended to reassure both Taiwan and the United States Congress that the US would continue to support Taiwan even if it had earlier cut formal diplomatic relations.

In the People's Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping formally retired after the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, to be succeeded by former Shanghai CCP secretary Jiang Zemin. During that period, also known as Jiangist China, the crackdown of the protests in 1989 led to great woes in China's reputation globally, and sanctions resulted. The situation, however, would eventually stabilize. Deng's idea of checks and balances in the political system also saw its demise with Jiang consolidating power in the party, state and military. The 1990s saw healthy economic development, but the closing of state-owned enterprises and increasing levels of corruption and unemployment, along with environmental challenges continued to plague China, as the country saw the rise to consumerism, crime, and new-age spiritual-religious movements such as Falun Gong. The 1990s also saw the peaceful handover of Hong Kong and Macau to Chinese control under the formula of One Country, Two Systems. China also saw a new surge of nationalism when facing crises abroad.

Cross-Strait relations are the relations between China and Taiwan.

The 1972 visit by United States President Richard Nixon to the People's Republic of China was an important strategic and diplomatic overture that marked the culmination of the Nixon administration's resumption of harmonious relations between the United States (U.S.) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) after years of diplomatic isolation. The seven-day official visit to three Chinese cities was the first time a U.S. president had visited the PRC; Nixon's arrival in Beijing ended 25 years of no communication or diplomatic ties between the two countries and was the key step in normalizing relations between the U.S. and the PRC. Nixon visited the PRC to gain more leverage over relations with the Soviet Union, following the Sino-Soviet Split. The normalization of ties culminated in 1979, when the U.S. established full diplomatic relations with the PRC.

The bilateral relationship between Taiwan and the United States of America is the subject of the Japan-U.S. relations during Japanese colonial rule and China-U.S. relations before the government of the Republic of China (ROC) led by the Kuomintang retreated to Taiwan and its neighboring islands as a result of the Chinese Civil War and until the U.S. ceased recognizing the ROC in 1979 as "China" as a result of the One China policy following the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations under the Carter administration. Prior to relations with the ROC, the United States had diplomatic relations with the Qing dynasty beginning on June 16, 1844 until 1912.

President Barack Obama's East Asia Strategy (2009–2017) represented a significant shift in the foreign policy of the United States. It took the country's focus from the Middle Eastern/European sphere and began to invest heavily in East Asian countries, some of which are in close proximity to the People's Republic of China.

With the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, American immigration policy towards Chinese emigrants and the highly controversial subject of foreign policy with regard to the PRC became invariably connected. The United States government was presented with the dilemma of what to do with two separate "Chinas". Both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China wanted be seen as the legitimate government and both parties believed that immigration would assist them in doing so.

The U.S.–China Relations Act of 2000 is an Act of the United States Congress that granted China permanent normal trade relations (NTR) status when China becomes a full member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), ending annual review and approval of NTR. It was signed into law on October 10, 2000, by United States President Bill Clinton. The Act also establishes a Congressional-Executive Commission to ensure that China complies with internationally recognized human rights laws, meets labor standards and allows religious freedom, and establishes a task force to prohibit the importation of Chinese products that were made in forced labor camps or prisons. The Act also includes so-called "anti-dumping" measures designed to prevent an influx of inexpensive Chinese goods into the United States that might hurt American industries making the same goods. It allows new duties and restrictions on Chinese imports that "threaten to cause market disruption to the U.S. producers of a like or directly competitive product."

China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on 11 December 2001, after the agreement of the Ministerial Conference. The admission of China to the WTO was preceded by a lengthy process of negotiations and required significant changes to the Chinese economy. China's membership in the WTO has been contentious, with substantial economic and political effects on other countries, and controversies over the mismatch between the WTO framework and China's economic model.

Ten United States presidents have made presidential visits to East Asia. The first presidential trip to a country in East Asia was made by Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952. Since then, all presidents, except John F. Kennedy, have traveled to one or more nations in the region while in office.

The People's Republic of China emerged as a great power and one of the three big players in the tri-polar geopolitics (PRC-US-USSR) during the late Cold war (1956-1991), after the Korean war in 1950-1953 and the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s, with its status as a recognized nuclear weapons state in 1960s. Currently, China has the world's largest population, second largest GDP (nominal) and the largest economy in the world by PPP. China is now considered an emerging global superpower.

US-China strategic engagement refers to a wide range of specific practices and interaction including economic cooperation, public diplomacy, military and foreign aid between the United States and China. This phase of engagement can be traced back to the late 1960s following an intense period of hostility caused by indirect confrontation between the two countries, particularly during the Korean War and the Vietnam War. With the US' support for Taiwan during the Taiwan Strait crises and its military expansion in the Pacific region, the relationship grew more antagonistic for the Chinese government perceive these initiatives to be US' attempt to encircle China. The domestic upheaval as a result of the Cultural Revolution in China and its commitment to communism through political radicalism accelerated the conflict. The four presidencies preceding the Bush administration were said to embrace a national policy direction toward strategic ambiguity, or deliberate ambiguity particularly in dealing with China. In October 2018, Vice President Mike Pence delivered a speech at the Hudson Institute on China, signifying the end of strategic engagement and officially proclaiming a new stage in the bilateral relationship, strategic competition.