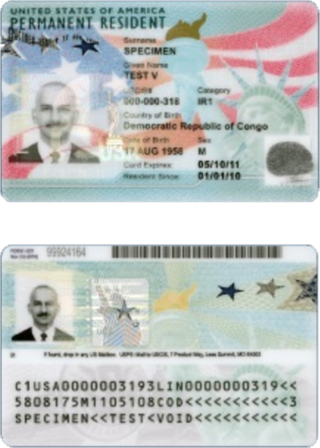

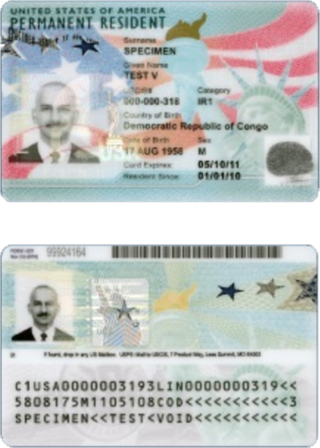

A green card, known officially as a permanent resident card, is an identity document which shows that a person has permanent residency in the United States. Green card holders are formally known as lawful permanent residents (LPRs). As of 2019, there are an estimated 13.9 million green card holders, of whom 9.1 million are eligible to become United States citizens. Approximately 65,000 of them serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, is a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The law abolished the National Origins Formula, which had been the basis of U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s. The act removed de facto discrimination against Southern and Eastern Europeans and Asians, as well as other non-Western and Northern European ethnic groups from American immigration policy.

The H-1B is a visa in the United States under the Immigration and Nationality Act, section 101(a)(15)(H) that allows U.S. employers to temporarily employ foreign workers in specialty occupations. A specialty occupation requires the application of specialized knowledge and a bachelor's degree or the equivalent of work experience. The duration of stay is three years, extendable to six years, after which the visa holder may need to reapply. Laws limit the number of H-1B visas that are issued each year: 188,100 new and initial H-1B visas were issued in 2019. Employers must generally withhold Social Security and Medicare taxes from the wages paid to employees in H-1B status.

The Diversity Immigrant Visa program, also known as the green card lottery, is a United States government lottery program for receiving a United States Permanent Resident Card. The Immigration Act of 1990 established the current and permanent Diversity Visa (DV) program.

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act, was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. It also authorized the creation of the country's first formal border control service, the U.S. Border Patrol, and established a "consular control system" that allowed entry only to those who first obtained a visa from a U.S. consulate abroad.

The Geary Act was a United States law that extended the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 by adding onerous new requirements. It was written by California Representative Thomas J. Geary and was passed by Congress on May 5, 1892.

The Immigration Act of 1990 was signed into law by George H. W. Bush on November 29, 1990. It was first introduced by Senator Ted Kennedy in 1989. It was a national reform of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. It increased total, overall immigration to allow 700,000 immigrants to come to the U.S. per year for the fiscal years 1992–94, and 675,000 per year after that. It provided family-based immigration visa, created five distinct employment based visas, categorized by occupation, and a diversity visa program that created a lottery to admit immigrants from "low admittance" countries or countries whose citizenry was underrepresented in the U.S.

An L-1 visa is a visa document used to enter the United States for the purpose of work in L-1 status. It is a non-immigrant visa, and is valid for a relatively short amount of time, from three months to five years, based on a reciprocity schedule. With extensions, the maximum stay is seven years.

The E-3 visa is a United States visa for which only citizens of Australia are eligible. It was created by an Act of the United States Congress as a result of the Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA), although it is not formally a part of the AUSFTA. The legislation creating the E-3 visa was signed into law by U.S. President George W. Bush on May 11, 2005. It is widely believed to have grown out of the negotiation of a trade deal between the US and Australia.

Illegal immigration to the United States is the process of migrating into the United States in violation of US immigration laws. This can include foreign nationals (aliens) who have entered the United States unlawfully, as well as those who lawfully entered but then remained after the expiration of their visas, parole, TPS, etc. Illegal immigration has been a matter of intense debate in the United States since the 1980s.

The Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act was a United States Senate bill introduced in the 109th Congress (2005–2006) by Sen. Arlen Specter (R-PE) on April 7, 2006. Co-sponsors, who signed on the same day, were Sen. Chuck Hagel (R-NE), Sen. Mel Martínez (R-FL), Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA), Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC), and Sen. Sam Brownback (R-KS).

The Security Through Regularized Immigration and a Vibrant Economy Act of 2007 or STRIVE Act of 2007 is proposed United States legislation designed to address the problem of illegal immigration, introduced into the United States House of Representatives. Its supporters claim it would toughen border security, increase enforcement of and criminal penalties for illegal immigration, and establish an employment verification system to identify illegal aliens working in the United States. It would also establish new programs for both illegal aliens and new immigrant workers to achieve legal citizenship. Critics allege that the bill would turn law enforcement agencies into social welfare agencies as it would not allow CBP to detain illegal immigrants that are eligible for Z-visas and would grant amnesty to millions of illegal aliens with very few restrictions.

The Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007 was a bill discussed in the 110th United States Congress that would have provided legal status and a path to citizenship for the approximately 12 million undocumented immigrants residing in the United States. The bill was portrayed as a compromise between providing a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and increased border enforcement: it included funding for 300 miles (480 km) of vehicle barriers, 105 camera and radar towers, and 20,000 more Border Patrol agents, while simultaneously restructuring visa criteria around high-skilled workers. The bill also received heated criticism from both sides of the immigration debate.

During the 18th and most of the 19th centuries, the United States had limited regulation of immigration and naturalization at a national level. Under a mostly prevailing "open border" policy, immigration was generally welcomed, although citizenship was limited to “white persons” as of 1790, and naturalization subject to five year residency requirement as of 1802. Passports and visas were not required for entry to America, rules and procedures for arriving immigrants were determined by local ports of entry or state laws, and processes for naturalization were determined by local county courts.

The Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013 was a proposed immigration reform bill introduced by Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) in the United States Senate. The bill was co-sponsored by the other seven members of the "Gang of Eight", a bipartisan group of U.S. Senators who wrote and negotiated the bill. It was introduced in the Senate on April 16, 2013 during the 113th United States Congress.

The American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act (ACWIA) was an act passed by the government of the United States on October 21, 1998, pertaining to high-skilled immigration to the United States, particularly immigration through the H-1B visa, and helping improving the capabilities of the domestic workforce in the United States to reduce the need for foreign labor.

The RAISE Act is a bill first introduced in the United States Senate in 2017. Co-sponsored by Republican senators Tom Cotton and David Perdue, the bill seeks to reduce levels of legal immigration to the United States by 50% by halving the number of green cards issued. The bill would also dramatically reduce family-based immigration pathways; impose a cap of 50,000 refugee admissions a year; end the visa diversity lottery; and eliminate the current demand-driven model of employment-based immigration and replace it with a points system. The bill received the support of President Donald Trump, who promoted a revised version of the bill in August 2017, and was opposed by Democrats, immigrant rights groups, and some Republicans.

Federal policy oversees and regulates immigration to the United States and citizenship of the United States. The United States Congress has authority over immigration policy in the United States, and it delegates enforcement to the Department of Homeland Security. Historically, the United States went through a period of loose immigration policy in the early-19th century followed by a period of strict immigration policy in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Policy areas related to the immigration process include visa policy, asylum policy, and naturalization policy. Policy areas related to illegal immigration include deferral policy and removal policy.

The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act is proposed United States federal legislation that would reform U.S. immigration policy, primarily by removing per-country limitations on employment-based visas, increasing the per-country numerical limitation for family-sponsored immigrants, and for other purposes. In 2020, for the first time it passed by House and Senate; however, the House and Senate versions were different and required reconciliation, and that reconciliation could not be carried out before the expiration of the 116th Congress. In order for the proposed legislation to further progress, it would have to be reintroduced into the 117th Congress and pass the House and Senate again.

The U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021 is a legislative bill that was proposed by President Joe Biden on his first day in office. It was formally introduced in the House by Representative Linda Sánchez.