Notes

- ↑ Barthel Beham, Christ and the Sheep Shed http://individual.utoronto.ca/mmilner/history2p91/primary/gei432.gif

- ↑ Lindberg (2007) , p. 76

- ↑ Dixon (1996) , p. 164

- 1 2 Moxey (1989) , p. 33

- ↑ Moxey (1989) , p. 29

- ↑ John 10: 8-9 The Shepherd and his Flock.

- ↑ Dixon C. Scott, "The Engraven Reformation", "© Case-study 2: The Engraven Reformation". Archived from the original on 2008-04-19. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ Moxey (1989) , p. 20

- ↑ Moxey (1989) , p. 21

- 1 2 Scribner (1987) , p. 287

- 1 2 Scribner (1987) , p. 277

- ↑ Briggs & Burke (2002) , p. 16

- ↑ Melton (2002) , p. 3

- ↑ Moxey (1989) , p. 22

- ↑ Moxey (1989) , p. 23

- ↑ Johann Herlot, The Massacre of Weinsberg http://individual.utoronto.ca/mmilner/history2p91/seminar/section8.htm

- ↑ Lindberg (2007) , p. 199

- ↑ Martin Luther, Against the Robbing and Murderous Hordes of Peasants http://individual.utoronto.ca/mmilner/history2p91/primary/rupp6213.htm

- ↑ Christensen (1979) , p. 197

- ↑ Christensen (1979) , p. 26

- ↑ Christensen (1979) , p. 27

- ↑ Moxey (1989) , p. 40

- ↑ Moxey (1989) , p. 198

- 1 2 Moxey (1989) , p. 24

- 1 2 3 Reinhart (1998) , p. 182

- ↑ Lindberg (2007) , p. 39

Related Research Articles

The Reformation was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in particular to papal authority, arising from what were perceived to be errors, abuses, and discrepancies by the Catholic Church. The Reformation was the start of Protestantism and the split of the Western Church into Protestantism and what is now the Roman Catholic Church. It is also considered to be one of the events that signify the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period in Europe.

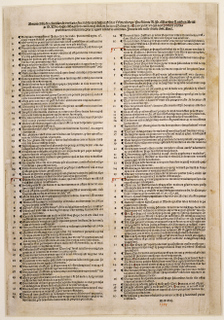

The Ninety-five Theses or Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences is a list of propositions for an academic disputation written in 1517 by Martin Luther, professor of moral theology at the University of Wittenberg, Germany, at the time controlled by the Electorate of Saxony. Retrospectively considered to signal the birth of Protestantism, this document advances Luther's positions against what he saw as the abuse of the practice of clergy selling plenary indulgences, which were certificates believed to reduce the temporal punishment in purgatory for sins committed by the purchasers or their loved ones. In the Theses, Luther claimed that the repentance required by Christ in order for sins to be forgiven involves inner spiritual repentance rather than merely external sacramental confession. He argued that indulgences led Christians to avoid true repentance and sorrow for sin, believing that they could forgo it by obtaining an indulgence. These indulgences, according to Luther, discouraged Christians from giving to the poor and performing other acts of mercy, which he attributed to a belief that indulgence certificates were more spiritually valuable. Though Luther claimed that his positions on indulgences accorded with those of the Pope, the Theses challenge a 14th-century papal bull stating that the pope could use the treasury of merit and the good deeds of past saints to forgive temporal punishment for sins. The Theses are framed as propositions to be argued in debate rather than necessarily representing Luther's opinions, but Luther later clarified his views in the Explanations of the Disputation Concerning the Value of Indulgences.

Thomas Müntzer was a German preacher and theologian of the early Reformation whose opposition to both Martin Luther and the Roman Catholic Church led to his open defiance of late-feudal authority in central Germany. Müntzer was foremost amongst those reformers who took issue with Luther's compromises with feudal authority. He became a leader of the German peasant and plebeian uprising of 1525 commonly known as the German Peasants' War. He was captured after the Battle of Frankenhausen, tortured and executed.

Andreas Rudolph Bodenstein von Karlstadt, better known as Andreas Karlstadt or Andreas Carlstadt or Karolostadt, or simply as Andreas Bodenstein, was a German Protestant theologian, University of Wittenberg chancellor, a contemporary of Martin Luther and a reformer of the early Reformation.

The Radical Reformation represented a response to corruption both in the Catholic Church and in the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th century, the Radical Reformation gave birth to many radical Protestant groups throughout Europe. The term covers radical reformers like Thomas Müntzer and Andreas Karlstadt, the Zwickau prophets, and Anabaptist groups like the Hutterites and the Mennonites.

The German Renaissance, part of the Northern Renaissance, was a cultural and artistic movement that spread among German thinkers in the 15th and 16th centuries, which developed from the Italian Renaissance. Many areas of the arts and sciences were influenced, notably by the spread of Renaissance humanism to the various German states and principalities. There were many advances made in the fields of architecture, the arts, and the sciences. Germany produced two developments that were to dominate the 16th century all over Europe: printing and the Protestant Reformation.

Heinrich Aldegrever or Aldegraf was a German painter and engraver. He was one of the "Little Masters", the group of German artists making small old master prints in the generation after Albrecht Dürer.

Protestantism originated from the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. The term Protestant comes from the Protestation at Speyer in 1529, where the nobility protested against enforcement of the Edict of Worms which subjected advocates of Lutheranism to forfeit of all their property. However, the theological underpinnings go back much further, as Protestant theologians of the time cited both Church Fathers and the Apostles to justify their choices and formulations. The earliest origin of Protestantism is controversial; with some Protestants today claiming origin back to people in the early church deemed heretical such as Jovinian and Vigilantius.

Sebald Beham (1500–1550) was a German painter and printmaker, mainly known for his very small engravings. Born in Nuremberg, he spent the later part of his career in Frankfurt. He was one of the most important of the "Little Masters", the group of German artists making prints in the generation after Dürer.

Barthel Beham (1502–1540) was a German engraver, miniaturist, and painter.

Lutheranism as a religious movement originated in the early 16th century Holy Roman Empire as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church. The movement originated with the call for a public debate regarding several issues within the Catholic Church by Martin Luther, then a professor of Bible at the young University of Wittenberg. Lutheranism soon became a wider religious and political movement within the Holy Roman Empire owing to support from key electors and the widespread adoption of the printing press. This movement soon spread throughout northern Europe and became the driving force behind the wider Protestant Reformation. Today, Lutheranism has spread from Europe to all six populated continents.

Hans Denck was a German theologian and Anabaptist leader during the Reformation.

Martin Luther was a German priest, theologian, author and hymnwriter. A former Augustinian friar, he is best known as the seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation and as the namesake of Lutheranism.

The Protestant Reformation during the 16th century in Europe almost entirely rejected the existing tradition of Catholic art, and very often destroyed as much of it as it could reach. A new artistic tradition developed, producing far smaller quantities of art that followed Protestant agendas and diverged drastically from the southern European tradition and the humanist art produced during the High Renaissance. The Lutheran churches, as they developed, accepted a limited role for larger works of art in churches, and also encouraged prints and book illustrations. Calvinists remained steadfastly opposed to art in churches, and suspicious of small printed images of religious subjects, though generally fully accepting secular images in their homes.

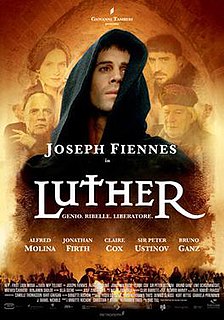

Luther is a 2003 historical drama film dramatizing the life of Protestant Christian reformer Martin Luther. It is directed by Eric Till and stars Joseph Fiennes in the title role. Alfred Molina, Jonathan Firth, Claire Cox, Bruno Ganz, and Sir Peter Ustinov co-star. The film covers Luther's life from his becoming a monk in 1505, to his trial before the Diet of Augsburg in 1530. The American-German co-production was partially funded by Thrivent, a Christian financial services company.

Propaganda during the Protestant Reformation, was helped by the spread of the printing press throughout Europe and in particular within Germany, caused new ideas, thoughts, and doctrine to be made available to the public in ways that had never been seen before the sixteenth century. The printing press was invented in approximately 1450 by Johan Gutenberg, and quickly spread to other major cities around Europe; by the time the Reformation was underway in 1517 there were printing centers in over 200 of the major European cities. These centers became the primary producers of Reformation works by the Protestants, and in some cases Counter-Reformation works put forth by the Roman Catholics.

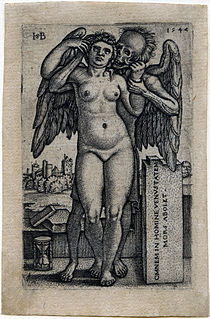

The Little Masters, were a group of German printmakers who worked in the first half of the 16th century, primarily in engraving. They specialized in very small finely detailed prints, some no larger than a postage stamp. The leading members were Hans Sebald Beham, his brother Barthel, and George Pencz, all from Nuremberg, and Heinrich Aldegrever and Albrecht Altdorfer. Many of the Little Masters' subjects were mythological or Old Testament stories, often treated erotically, or genre scenes of peasant life. The size and subject matter of the prints shows that they were designed for a market of collectors who would keep them in albums, of which a number have survived.

The German Peasants' War, Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt was a widespread popular revolt in some German-speaking areas in Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It failed because of intense opposition from the aristocracy, who slaughtered up to 100,000 of the 300,000 poorly armed peasants and farmers. The survivors were fined and achieved few, if any, of their goals. Like the preceding Bundschuh movement and the Hussite Wars, the war consisted of a series of both economic and religious revolts in which peasants and farmers, often supported by Anabaptist clergy, took the lead. The German Peasants' War was Europe's largest and most widespread popular uprising prior to the French Revolution of 1789. The fighting was at its height in the middle of 1525.

"Godless painters" is a term used by art historians to refer to Sebald Beham, his brother Barthel, and George Pencz, as exemplified in the title of a 2011 catalog of the Beham brothers' works, The Godless Painters of Nuremberg: Convention and Subversion in the Printmaking of the Beham Brothers. The epithet was coined in derision of the three painters during an inquest conducted by the Lutheran dominated city council of Nuremberg in 1525, which concerned the artists' protestant heterodoxy. The term is a double entendre eluding more to the content of the "godless painters" works, rather than the doctrinal views for which they were condemned. The typically small-scale prints often depicted biblical or moral themes with a touch of eroticism. The "godless painters" are also considered to be leading representatives of the group of little masters.

Lutheran art consists of all religious art produced for Lutherans and the Lutheran churches. This includes sculpture, painting, and architecture. Artwork in the Lutheran churches arose as a distinct marker of the faith during the Reformation era and attempted to illustrate, supplement and portray in tangible form the teachings of Lutheran theology.

References

- Briggs, Asa; Burke, Peter (2002). A Social History of the Media: From Gutenburd to the Internet. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Christensen, Carl C. (1979). Art and the Reformation in Germany. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado.

- Dixon, C. Scott (1996). The Reformation and Rural Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lindberg, Carter (2007). The European Reformations. Boston: Blackwell Publishing.

- Melton, James Van Horn (2002). Cultures of Communication from Reformation to Enlightenment. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing.

- Moxey, Keith (1989). Peasants, Warriors and Wives: Popular Imagery in the Reformation. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Reinhart, Max (1998). Infinite Boundaries: Order, Disorder and Reorder in Early Modern German Culture. Kirksville: Sixteenth Century Journal Publishers.

- Scribner, R. W. (1987). Popular Culture and Popular Movements in Reformation Germany. London: The Hambledon Press.