The Royal Palace of Madrid is the official residence of the Spanish royal family at the city of Madrid, although now used only for state ceremonies. The palace has 135,000 m2 (1,450,000 sq ft) of floor space and contains 3,418 rooms. It is the largest royal palace in Europe.

The Puerta del Sol is a public square in Madrid, one of the best known and busiest places in the city. This is the centre of the radial network of Spanish roads. The square also contains the famous clock whose bells mark the traditional eating of the Twelve Grapes and the beginning of a new year. The New Year's celebration has been broadcast live since 31 December 1962 on major radio and television networks including Atresmedia and RTVE.

The Albaicín, also known as Albayzín, is a district of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. It is centered around a hill on the north side of the Darro River which passes through the city. The neighbourhood is notable for its historic monuments and for largely retaining its medieval street plan dating back to the Nasrid period, although it nonetheless went through many physical and demographic changes after the end of the Reconquista in 1492. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1994, as an extension of the historic site of the nearby Alhambra.

La Latina is a historic neighborhood in the Centro district of downtown Madrid, Spain. La Latina occupies the place of the oldest area in Madrid, the Islamic citadel inside the city walls, with narrow streets and large squares. It is administratively locked almost entirely within the district of Palacio in Centro. It was named after the old hospital, founded in 1499 by Beatriz Galindo "La Latina". It occupies a large part of what is known as El Madrid de los Austrias, and although its boundaries are subjective, it could be argued that it was essentially the vicinity of the San Francisco Racecourse - that continues from the Plaza de la Cebada up to the San Francisco el Grande Basilica. These limits are: to the north, Segovia street - a deep ravine formerly occupied by the San Pedro Stream which empties into the Manzanares River, to the south there is la Ronda and Puerta de Toledo, on the east there is Toledo street - bordering Rastro and the district of Lavapiés - and to the west, Bailen street.

The main components of the Coat of arms of Madrid have their origin in the Middle Ages. The different coats of arms have experienced several modifications, losing for example motifs often displayed in early designs such as water and flint.

The Gate of the Ears, also known as the Arc of the Ears or Bib-Arrambla Gate, was a city gate of Granada. Built in the 11th or 12th century, it stood at the corner of Plaza de Bib-Rambla and Calle Salamanca. During the 19th century, the gate became the subject of several major controversies, and in 1884 it was demolished.

The Walls of Seville are a series of defensive walls surrounding the Old Town of Seville. The city has been surrounded by walls since the Roman period, and they were maintained and modified throughout the subsequent Visigoth, Islamic and finally Castilian periods. The walls remained intact until the 19th century, when they were partially demolished after the revolution of 1868. Some parts of the walls still exist, especially around the Alcázar of Seville and some curtain walls in the barrio de la Macarena.

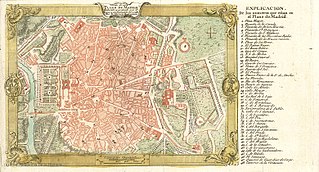

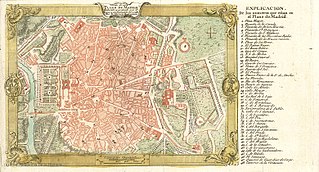

The Walls of Felipe IV surrounded the city of Madrid between 1625 and 1868. Philip IV ordered their construction to replace the earlier Walls of Philip II and the Walls del Arrabal, which had already been surpassed by the growth of population of Madrid. These were not defensive walls, but essentially served fiscal and surveillance purposes: to control the access of goods to the city, ensure the collection of taxes, and to monitor who went in and out of Madrid. The materials used for construction were brick, mortar and compacted earth.

The Walls of Madrid are the five successive sets of walls that surrounded the city of Madrid from the Middle Ages until the end of the 19th century. Some of the walls had a defensive or military function, while others made it easy to tax goods entering the city. Towards the end of the 19th century the demographic explosion that came with the Industrial Revolution prompted urban expansion throughout Spain. Older walls were torn down to enable the expansion of the city under the grid plan of Carlos María de Castro.

The Muslim Walls of Madrid, of which some vestiges remain, are located in the Spanish city of Madrid. They are probably the oldest construction extant in the city. They were built in the 9th century, during the Muslim domination of the Iberian Peninsula, on a promontory next to Manzanares river. They were part of a fortress around which developed the urban nucleus of Madrid. They were declared an Artistic-Historic Monument in 1954.

The Walls del Arrabal were the third in a set of five walls built around Madrid, now the capital of Spain. There are no remaining ruins of the Walls del Arrabal, leaving some debate as to their extent and the period of their construction. It is possible that the walls were built as early as the 12th century, however they were most likely constructed in 1438. The walls may have been intended to protect people against the plagues that ravaged the city at the time. The walls united the urbanized suburbs of the city and prevented entry of the infected.

The Walls of Philip II were walls in the city of Madrid that Philip II, in 1566, constructed for fiscal and sanitary control. The walls covered an area of about 125 hectares.]

The Puerta de Triana was the generic name for an Almohad gate and a Christian gate rose in the same place. It was one of the gates of the walled enclosure of Seville (Andalusia).

Puerta del Campo was a city gate in Valladolid, Spain, named after the street that ran through it. Until at least the 18th century, it lent its name to the surrounding area.

Old Town of Cáceres is a historic walled city in Cáceres, Spain.

The Plaza de Isabel II is a historic public square between the Sol and Palacio wards in the central district of Madrid. The plaza is at the convergence of Arenal Street and the minor roads Arrieta, Calle de Campomanes, Caños del Peral, Escalinata and Vergara. It was formed by filling the ravine created by the Arenal stream and the source of the Fountain of the Canals of the Pear Tree. The square occupies part of the site where the old Theater of the Caños del Peral stood between 1738 and 1817.

The historic centre of Pontevedra (Spain) is the oldest part of the city. It is the second most important old town in Galicia after Santiago de Compostela, and was declared a historic-artistic complex on 23 February 1951.

The Arrabal of Saint Martin was a medieval arrabal (neighborhood) that sat outside the Christian Walls of Madrid. It was located around the location of the current Plaza of San Martín, and occupied the space between Calle del Arenal, the Plaza de las Descalzas, Plaza del Callao, and Calle de las Navas de Tolosa. It grew as a population center around the Monastery of Saint Martin, neighboring San Martín was the Arrabal of San Ginés, and both were absorbed by the growth of the city in the 17th century.

The Tower of Bones is an Islamic watchtower, the remains of which are exhibited in the underground parking structure in the Plaza de Oriente, in the Spanish city of Madrid. It was built in the 11th century by the Muslim population that founded the Mayrit fortress two centuries earlier, as an integral part of its defensive system.

The history of the Puerta del Sol represents an essential part of the memory of the Villa de Madrid, not only because the Puerta del Sol is a point of frequent passage, but also because it constitutes the "center of gravity" of Madrid's urban planning. The square has been acquiring its character as a place of historical importance from its uncertain beginnings as a wide and impersonal street in the sixteenth century, to the descriptions of the first romantic travelers, the receptions of kings, popular rebellions, demonstrations, etc. It has been the scene of major events in the life of the city, from the struggle against the French invaders in 1808 to the proclamation of the Second Republic in 1931, and it has also retained its place as the protagonist of the custom of serving twelve grapes on New Year's Eve, to the sound of the chimes struck by the Correos clock. Nowadays it is a communications hub, a meeting point, a place of appointments, a place for celebrations and the beginning of demonstrations in the Capital.