Related Research Articles

Ironbridge is a large village in the borough of Telford and Wrekin in Shropshire, England. Located on the bank of the River Severn, at the heart of the Ironbridge Gorge, it lies in the civil parish of The Gorge. Ironbridge developed beside, and takes its name from, The Iron Bridge, a 100-foot (30 m) cast iron bridge that was built in 1779.

Telford is a town in Shropshire, England. It is the administrative centre of Telford and Wrekin borough, a unitary authority which covers the town, its suburbs and surrounding settlements. The town is inland and near the River Severn.

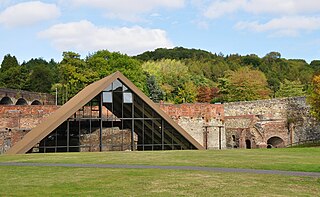

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

Donnington is an area / housing estate located in the borough of Telford and Wrekin and ceremonial county of Shropshire, England. The population of Donnington Ward was 6,883 at the 2011 census.

Dawley is a constituent town of Telford and a civil parish in the borough of Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. It was originally, in 1963, going to be the main centre of the 'Dawley New Town' plan before it was decided in 1968 to name the new town as 'Telford', after the engineer and road-builder Thomas Telford. Dawley now forms part of Telford whose town centre is north of Dawley itself.

The Telford Steam Railway (TSR) is a heritage railway located at Horsehay, Telford in Shropshire, England, formed in 1976.

Madeley is a constituent town of Telford and a civil parish in the borough of Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. The parish had a population of 17,935 at the 2001 census.

Abraham Darby III was an English ironmaster and Quaker. He was the third man of that name in several generations of an English Quaker family that played a pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution.

Coalport is a village in Shropshire, England. It is located on the River Severn in the Ironbridge Gorge, a mile downstream of Ironbridge. It lies predominantly on the north bank of the river; on the other side is Jackfield.

The A442 is a main road which passes through the counties of Worcestershire and Shropshire, in the West Midlands region of England.

The Iron Bridge is a cast iron arch bridge that crosses the River Severn in Shropshire, England. Opened in 1781, it was the first major bridge in the world to be made of cast iron. Its success inspired the widespread use of cast iron as a structural material, and today the bridge is celebrated as a symbol of the Industrial Revolution.

Horsehay is a suburban village on the western outskirts of Dawley, which, along with several other towns and villages, now forms part of the new town of Telford in Shropshire, England. Horsehay lies in the Dawley Hamlets parish, and on the northern edge of the Ironbridge Gorge area.

The Shropshire Canal was a tub boat canal built to supply coal, ore and limestone to the industrial region of east Shropshire, England, that adjoined the River Severn at Coalbrookdale. It ran from a junction with the Donnington Wood Canal ascending the 316 yard long Wrockwardine Wood inclined plane to its summit level, it made a junction with the older Ketley Canal and at Southall Bank the Coalbrookdale (Horsehay) branch went to Brierly Hill above Coalbrookdale; the main line descended via the 600 yard long Windmill Incline and the 350 yard long Hay Inclined Plane to Coalport on the River Severn. The short section of the Shropshire Canal from the base of the Hay Inclined Plane to its junction with the River Severn is sometimes referred to as the Coalport Canal.

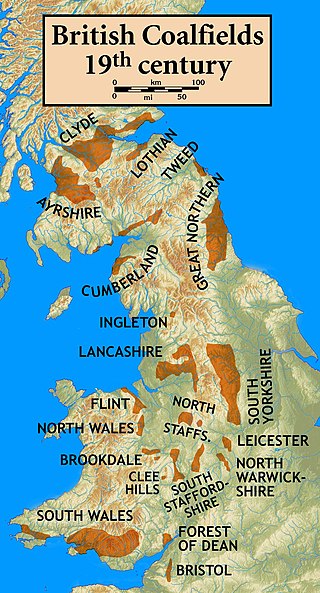

The Coalbrookdale Coalfield is a coalfield in Shropshire in the English Midlands. It extends from Broseley in the south, northwards to the Boundary Fault which runs northeastwards from the vicinity of The Wrekin past Lilleshall. The former coalfield has been built on by the new town of Telford.

Resolution was an early beam engine, installed between 1781 and 1782 at Coalbrookdale as a water-returning engine to power the blast furnaces and ironworks there. It was one of the last water-returning engines to be constructed, before the rotative beam engine made this type of engine obsolete.

William Reynolds was an ironmaster and a partner in the ironworks in Coalbrookdale in Shropshire, England. He was interested in advances in science and industry, and invented the inclined plane for canals.

William "Billy" Ball (1795–1852), the "Shropshire Giant", was a nineteenth-century iron puddler and "giant".

Barrie Stuart Trinder is a British historian and writer on industrial archaeology. After a career in teaching, he took a PhD with the University of Leicester, graduating in 1980 for a thesis on the history of Banbury. He then became a research fellow at the Ironbridge Institute, and later lectured on industrial archaeology at Nene College of Higher Education in Northampton. He was a founder member of The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH). He has written and edited on the history of Banbury, on Shropshire, and on the industrial archaeology and industrial history of Britain generally. He edited The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Industrial Archaeology (1992). He was made a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 2000.

References

- ↑ "Disturbances Near Wellington". Salopian Journal. 7 February 1821.

- ↑ Growcott, Mat (6 October 2018). "The riot that Telford forgot: New group trying to raise awareness of Cinderloo uprising". Shropshire Star. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ Raistrick, Arthur (1989). Dynasty of Iron Founders: the Darbys and Coalbrookdale. Coalbrookdale: Sessions Book Trust/Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. ISBN 1-85072-058-4.

- ↑ Trinder, Barrie (2000). The Industrial Revolution in Shropshire (Third ed.). Chichester: Phillimore. p. 159. ISBN 9780750967877.

- ↑ "Fatal Riot". Shrewsbury Chronicle. 9 February 1821.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gladstone, E.W. (1953). The Shropshire Yeomanry 1795-1945, the Story of a Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. The Whitethorn Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Mercer, A. C. B (January 1966). "Cinderloo Affair". Shropshire Magazine.

- ↑ Trinder, Barrie (2000). The Industrial Revolution in Shropshire (Third ed.). Chichester: Phillimore. pp. 232–233. ISBN 9781860771330.

- ↑ Cludde, W (4 February 1821). to H.O. PRO HO 40/16/15.

- ↑ "The Wellington Rioters". Shrewsbury Chronicle. 30 March 1821.

- ↑ The account on page 21 of The Shropshire Yeomanry by E.W. Gladstone, states "One of the rioters was killed and several wounded, two more would die afterwards" [emphasis added].

- ↑ "Disturbances near Wellington". Salopian Journal. 7 February 1821.

- ↑ Talbot, Phillip (Spring 2001). "The English Yeomanry In The Nineteenth Century And The Great Boer War". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 79 (317): 48.

- ↑ The Shropshire Yeomanry 1795-1945 by E.W. Gladstone, page 22.

- ↑ Trinder, Barrie (2000). The Industrial Revolution in Shropshire (3 ed.). Chichester: Phillimore. p. 233. ISBN 9781860771330.

- ↑ "Trial of the Colliers". Salopian Journal. 28 March 1821.

- ↑ "Execution". Salopian Journal. 11 April 1821.

- ↑ Growcott, Mat (26 February 2019). "'Cinderloo Bridge'?: Campaigners call for Telford's new £10 million footbridge to be named after 1821 uprising". Shropshire Star. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ "Newsroom - Telford bridge renamed Cinderloo to mark 200th anniversary". newsroom.telford.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ↑ Bentley, Charlotte. "Telford bridge renamed 'Cinderloo' after historic uprising". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.