The Whigs were a political party in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. Between the 1680s and the 1850s, the Whigs contested power with their rivals, the Tories. The Whigs became the Liberal Party when the faction merged with the Peelites and Radicals in the 1850s. Many Whigs left the Liberal Party in 1886 over the issue of Irish Home Rule to form the Liberal Unionist Party, which merged into the Conservative Party in 1912.

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–1835). He previously was Home Secretary twice. He is regarded as the father of modern British policing, owing to his founding of the Metropolitan Police while he was Home Secretary. Peel was one of the founders of the modern Conservative Party.

The Representation of the People Act 1832 was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that introduced major changes to the electoral system of England and Wales. It reapportioned constituencies to address the unequal distribution of seats and expanded franchise by broadening and standardising the property qualifications to vote.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form for over a century. In 1927, it evolved into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, after the Irish Free State gained a degree of independence in 1922.

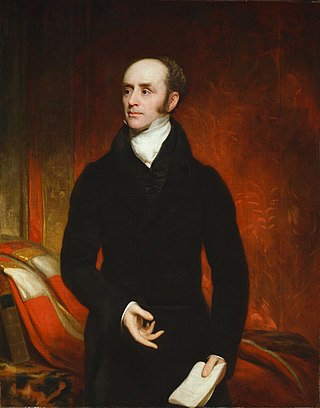

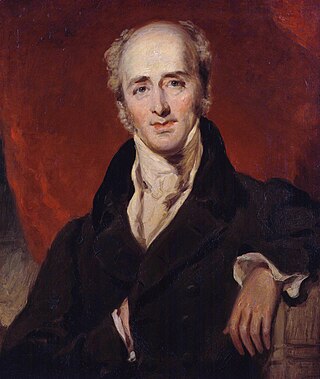

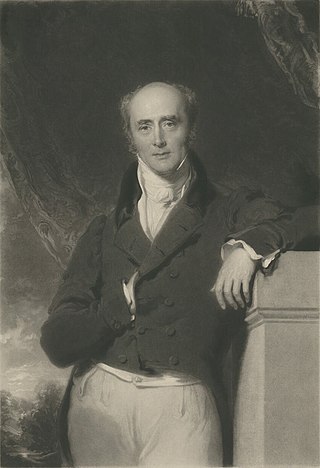

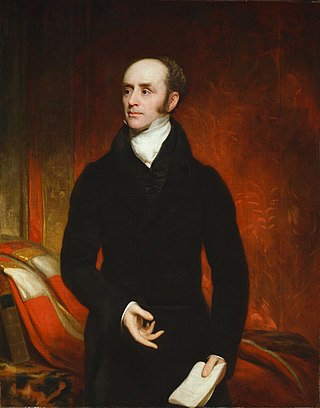

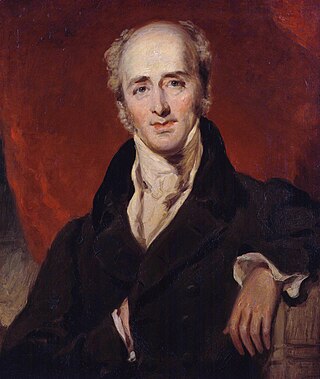

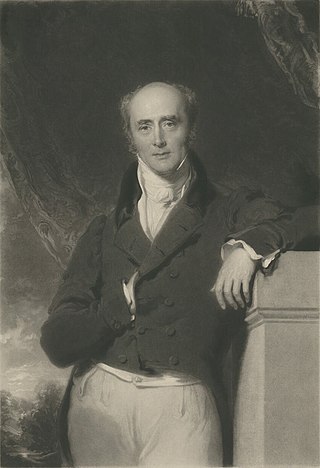

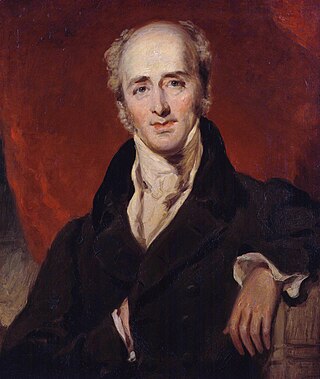

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, known as Viscount Howick between 1806 and 1807, was a British Whig politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1830 to 1834. He was a descendant of the House of Grey and the namesake of Earl Grey tea. Grey was a long-time leader of multiple reform movements. During his time as prime minister, his government brought about two notable reforms. The Reform Act 1832 enacted parliamentary reform, greatly increasing the electorate of the House of Commons.

The Reform Acts are legislation enacted in the United Kingdom in the 19th and 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. When short titles were introduced for these acts, they were usually Representation of the People Act.

The 1832 United Kingdom general election was held on 8 December 1832 to 8 January 1833, to elect members of the House of Commons, the lower house of Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was the first held in the Reformed House of Commons following the Reform Act, which introduced significant changes to the electoral system.

The Radicals were a loose parliamentary political grouping in Great Britain and Ireland in the early to mid-19th century who drew on earlier ideas of radicalism and helped to transform the Whigs into the Liberal Party.

The Swing Riots were a widespread uprising in 1830 by agricultural workers in southern and eastern England in protest of agricultural mechanisation and harsh working conditions. The riots began with the destruction of threshing machines in the Elham Valley area of East Kent in the summer of 1830 and by early December had spread through the whole of southern England and East Anglia. It was to be the largest movement of social unrest in 19th-century England.

The Whig government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that began in November 1830 and ended in November 1834 consisted of two ministries: the Grey ministry and then the first Melbourne ministry.

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, removed the sacramental tests that barred Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom from Parliament and from higher offices of the judiciary and state. It was the culmination of a fifty-year process of Catholic emancipation which had offered Catholics successive measures of "relief" from the civil and political disabilities imposed by Penal Laws in both Great Britain and in Ireland in the seventeenth, and early eighteenth, centuries.

The "unreformed House of Commons" is a name given to the House of Commons of Great Britain before it was reformed by the Reform Act 1832, the Irish Reform Act 1832, and the Scottish Reform Act 1832.

The 1831 United Kingdom general election was held on 28 April 1831 to 1 June 1831, to elect members of the House of Commons, the lower house of Parliament. It saw a landslide win by supporters of electoral reform, which was the major election issue. As a result, it was the last unreformed election, as the following Parliament ensured the passage of the Reform Act 1832. Polling was held from 28 April to 1 June 1831. The Whigs won a majority of 136 over the Tories, which was as near to a landslide as the unreformed electoral system could deliver. As the Government obtained a dissolution of Parliament once the new electoral system had been enacted, the resulting Parliament was a short one and there was another election the following year. The election was the first since 1715 to see a victory by a party previously in minority.

The 1830 United Kingdom general election was held on 29 July 1830 to 1 September 1830 to elect members of the House of Commons, the lower house of Parliament. Triggered by the death of King George IV, it produced the first parliament of the reign of his successor, King William IV. Fought in the aftermath of the Swing Riots, it saw electoral reform become a major election issue. Polling took place in July and August and the Tories won a plurality over the Whigs, but division among Tory MPs allowed Earl Grey to form an effective government and take the question of electoral reform to the country the following year.

The Birmingham Political Union was a grass roots pressure group in Great Britain during the 1830s. It was founded by Thomas Attwood, a banker interested in monetary reform. Its platform called for extending and redistributing suffrage rights to the working class, of the kind set out in the Reform Bill of March 1831 which when passed became the Reform Act 1832. It included both middle-class and working-class members.

Joseph Parkes was an English political reformer.

The Ultra-Tories were an Anglican faction of British and Irish politics that appeared in the 1820s in opposition to Catholic emancipation. The faction was later called the "extreme right-wing" of British and Irish politics.

The National Political Union (NPU) was an organisation set up in October 1831, after the rejection of the Reform Bill by the House of Lords, to serve as a pressure group for parliamentary reform: “to support the King and his ministers against a small faction in accomplishing their great measure of Parliamentary Reform”.

The 1831 reform riots occurred after the Second Reform Bill was defeated in Parliament in October 1831. There were civil disturbances in London, Leicester, Yeovil, Sherborne, Exeter, Bath and Worcester and riots at Nottingham, Derby and Bristol. Targets included Nottingham Castle, home of the anti-reform Duke of Newcastle, other private houses and jails. In Bristol, three days of rioting followed the arrival in the city of the anti-reform judge Charles Wetherell; a significant portion of the city centre was burnt, £300,000 of damage inflicted and up to 250 casualties occurred.

The 1831 Bristol riots took place on 29–31 October 1831 and were part of the 1831 reform riots in England. The riots arose after the second Reform Bill was voted down in the House of Lords, stalling efforts at electoral reform. The arrival of the anti-reform judge Charles Wetherell in the city on 29 October led to a protest, which degenerated into a riot. The civic and military authorities were poorly focused and uncoordinated and lost control of the city. Order was restored on the third day by a combination of a posse comitatus of the city's middle-class citizens and military forces.