Related Research Articles

The Indian National Army was a collaborationist armed unit of Indian collaborators that fought under the command of the Japanese Empire. It was founded on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II.

Subhas Chandra Bose was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan left a legacy vexed by authoritarianism, anti-Semitism, and military failure. The honorific Netaji was first applied to Bose in Germany in early 1942—by the Indian soldiers of the Indische Legion and by the German and Indian officials in the Special Bureau for India in Berlin. It is now used throughout India.

During the Second World War (1939–1945), India was a part of the British Empire. India officially declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939. India, as a part of the Allied Nations, sent over two and a half million soldiers to fight under British command against the Axis powers. India also provided the base for American operations in support of China in the China Burma India Theater.

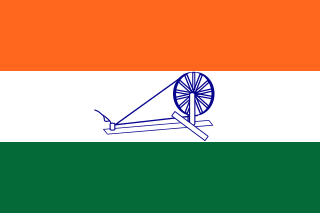

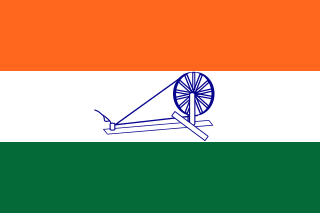

The Provisional Government of Free India or, more simply, Azad Hind, was a short-lived Japanese-supported provisional government in India. It was established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II in October 1943 and has been considered a puppet state of Empire of Japan.

The Indian Legion, officially the Free India Legion or 950th (Indian) Infantry Regiment, was a military unit raised during the Second World War initially as part of the German Army and later the Waffen-SS from August 1944. Intended to serve as a liberation force for British-ruled India, it was made up of Indian prisoners of war and expatriates in Europe. Due to its origins in the Indian independence movement, it was known also as the "Tiger Legion", and the "Azad Hind Fauj". As part of the Waffen-SS it was known as the Indian Volunteer Legion of the Waffen-SS.

Mohan Singh was an Indian military officer, Japanese collaborator and member of the Indian Independence Movement best known for organising and leading the Indian National Army in South East Asia during World War II. Following Indian independence, Mohan Singh later served in public life as a Member of Parliament in the Rajya Sabha of the Indian Parliament. He was a member of the Indian National Army (INA).

The Indian Independence League was a political organisation operated from the 1920s to the 1940s to organise those living outside India into seeking the removal of British colonial rule over India. Founded by Indian nationalists, its activities were conducted in various parts of Southeast Asia. It included Indian expatriates, and later, Indian nationalists in-exile under Japanese occupation following Japan's successful Malayan Campaign during the first part of the Second World War. During the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, the Japanese encouraged Indians in Malaya to join the League.

The Indian National Army trials was the British Indian trial by court-martial of a number of officers of the Indian National Army (INA) between November 1945 and May 1946, on various charges of treason, torture, murder and abetment to murder, during the Second World War. In total, approximately ten court-martials were held. The first of these was the joint court-martial of Colonel Prem Sahgal, Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon, and Major-General Shah Nawaz Khan. The three had been officers in the British Indian Army and were taken prisoner in Malaya, Singapore and Burma. They had, alongside a large number of other troops and officers of the British Indian Army, joined the Indian National Army and later fought in Burma alongside the Japanese military under the Azad Hind.

The Bidadari Resolutions were set of resolutions adopted by the nascent Indian National Army in April 1942 that declared the formation of the INA and its aim to launch an armed struggle for Indian independence. The resolution was declared at a prisoner-of-war camp at the Bidadari in Singapore during Japanese occupation of the island.

Major General Arcot Doraiswamy Loganadan was an officer of the Indian National Army, and a minister in the Azad Hind Government as a representative of the Indian National Army. He also served briefly as their Governor for the Andaman Islands and Burma.

Jiffs was a slang term used by British Intelligence, and later the 14th Army, to denote soldiers of the Indian National Army after the failed First Arakan offensive of 1943. The term is derived from the acronym JIFC, short for Japanese-Indian fifth column. It came to be employed in a propaganda offensive in June 1943 within the British Indian Army as a part of the efforts to preserve the loyalty of the Indian troops at Manipur after suffering desertion and losses at Burma during the First Arakan Offensive. After the end of the war, the term "HIFFs" was also used for repatriated troops of the Indian Legion awaiting trial.

The First Indian National Army was the Indian National Army as it existed between February and December 1942. It was formed with Japanese aid and support after the Fall of Singapore and consisted of approximately 12,000 of the 40,000 Indian prisoners of war who were captured either during the Malayan campaign or surrendered at Singapore and was led by Rash Behari Bose of Japan. It was formally proclaimed in April 1942 and declared the subordinate military wing of the Indian Independence League in June that year. The unit was dissolved in December 1942 after apprehensions of Japanese motives with regards to the INA led to disagreements and distrust between Mohan Singh and INA leadership on one hand, and the League's leadership, most notably Rash Behari Bose, who handed over the Indian National Army to Subhas Chandra Bose but remained as Supreme Advisor to INA. A large number of the INAs initial volunteers, however, later went on to join the INA in its second incarnation under Subhas Chandra Bose.

The Farrer Park address was an assembly of the surrendered Indian troops of the British Indian Army held at Farrer Park in Singapore on 17 February 1942, two days after the Fall of Singapore. The assembly was marked by a series of three addresses in which the British Malaya Command formally surrendered the Indian troops of the British Indian Army to Major Fujiwara Iwaichi representing the Japanese military authority, followed by transfer of authority by Fujiwara to the command of Mohan Singh, and a subsequent address by Mohan Singh to the gathered troops declaring the formation of the Indian National Army to fight the Raj, asking for volunteers to join the army.

The Battles and Operations involving the Indian National Army during World War II were all fought in the South-East Asian theatre. These range from the earliest deployments of the INA's preceding units in espionage during Malayan Campaign in 1942, through the more substantial commitments during the Japanese Ha Go and U Go offensives in the Upper Burma and Manipur region, to the defensive battles during the Allied Burma campaign. The INA's brother unit in Europe, the Indische Legion did not see any substantial deployment although some were engaged in Atlantic wall duties, special operations in Persia and Afghanistan, and later a small deployment in Italy. The INA was not considered a significant military threat. However, it was deemed a significant strategic threat especially to the Indian Army, with Wavell describing it as a target of prime importance.

Subh Sukh Chain was the national anthem of the Provisional Government of Free India.

Habib ur Rahman (1913–1978) was an army officer in the Indian National Army (INA) who was charged with "waging war against His Majesty the King Emperor". He served as Subhas Chandra Bose's chief of staff in Singapore, and accompanied Bose on his alleged last fatal flight from Taipei to Tokyo, sharing the last moments of his life. Rahman also played an important role in the First Kashmir War. Convinced that Maharaja Hari Singh was out to exterminate the Muslims of Jammu and Kashmir, he joined Major General Zaman Kiani, in launching a rebellion against the Maharaja from Gujrat in Pakistani Punjab. Rehman and his volunteer force launched an attack on the Bhimber town. But, the records of the 11th Cavalry of the Pakistan Army indicate that their efforts did not succeed, and eventually the Cavalry was responsible for conquering Bhimber.

Throughout World War II, both the Axis and Allied sides used propaganda to sway the opinions of Indian civilians and troops, while at the same time Indian nationalists applied propaganda both within and outside India to promote the cause of Indian independence.

The Indian National Army (INA) and its leader Subhash Chandra Bose are popular and emotive topics within India. From the time it came into public perception in India around the time of the Red Fort Trials, it found its way into the works of military historians around the world. It has been the subject of a number of projects, of academic, historical and of popular nature. Some of these are critical of the army, some — especially of the ex-INA men — are biographical or autobiographical, while still others historical and political works, that tell the story of the INA. A large number of these provide analyses of Subhas Chandra Bose and his work with the INA.

The INA treasure controversy relates to alleged misappropriation by men of Azad Hind of the Azad Hind fortune recovered from belongings of Subhas Chandra Bose in his last known journey. The treasure, a considerable amount of gold ornaments and gems, is said to have been recovered from Bose's belongings following the fatal plane crash in Formosa that reportedly killed him, and taken to men of Azad Hind then living in Japan. The Indian government was made aware of a number of these individuals allegedly using part of the recovered treasure for personal use. However, despite repeated warnings from Indian diplomats in Tokyo, Nehru is said to have disregarded allegations that men previously associated with Azad Hind misappropriated the funds for personal benefit. Some of these are said to have travelled to Japan repeatedly with the approval of Nehru government and were later given government roles implementing Nehru's political and economic agenda. A very small portion of the alleged treasure was repatriated to India in the 1950s.

The Indian National Army (INA) was a Japanese sponsored Indian military wing in Southeast Asia during the World War II, particularly active in Singapore, that was officially formed in April 1942 and disbanded in August 1945. It was formed with the help of the Japanese forces and was made up of roughly about 45 000 Indian prisoner of war (POWs) of British Indian Army, who were captured after the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942. It was initially formed by Rash Behari Bose who headed it till April 1942 before handing the lead of INA over to Subhas Chandra Bose in 1943.

References

- 1 2 Fay 1993 , pp. 423–424, 453

- 1 2 Aldrich 2000 , p. 163

- ↑ Fay 1993 , pp. 461–463

- ↑ William L Farrow. "Indian National Army (Japanese Independent Force)". BBC. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ↑ Green 1948 , p. 45,46

- 1 2 3 Fay 1993 , p. 83

- ↑ Singapore's Changi Museum records undeniable history

- 1 2 Menon 1997 , p. 225

- ↑ Fay 1993 , p. 290

- ↑ Aldrich 2000 , p. 159

- 1 2 Fay 1993 , p. 427

- ↑ Thompson 2005 , p. 389

- ↑ "INA war veterans get a warm welcome". The Times of India . 18 April 2004. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- 1 2 Allen 1971 , p. 91

- ↑ Fay 1993 , p. 450

- ↑ Ghosh 1969

- ↑ Sarkar 1983 , p. 411

- ↑ Fay 1993 , p. 485

- ↑ Cohen 1971 , p. 132

- 1 2 Shaikh, Sajid (6 October 2001). "INA's soldier lives in oblivion in Vadodara". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ↑ Green 1948 , p. 68

- ↑ "Radhakrishnan met Netaji in Moscow, says witness". Hindustan Times . 17 November 1970. Archived from the original on 26 April 2005. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ↑ "Gandhi, others had agreed to hand over Netaji". Hindustan Times. 23 January 1971. Archived from the original on 21 February 2004. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- 1 2 Shahira Naim. "The Bose I knew is a memory now - Lakshmi Sahgal". The Tribune. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ↑ Sumit Ganguly. "Explaining India's Transition to Democracy ". Columbia University Press. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ↑ Pratibha Chauhan. "INA hero gets shabby treatment". Tribune News Service. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ↑ "INA hero Ram Singh dead". The Times of India. 16 April 2002. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- 1 2 3 Kavitha Muralidharan. "Who shrunk Netaji's fortune?". India Today. Retrieved 19 September 2015.