The American horned owls and the Old World eagle-owls make up the genus Bubo, at least as traditionally described. The genus name Bubo is Latin for the Eurasian eagle-owl.

The New World vulture or condor family, Cathartidae, contains seven extant species in five genera. It includes five extant vultures and two extant condors found in warm and temperate areas of the Americas. The "New World" vultures were widespread in both the Old World and North America during the Neogene.

The black vulture, also known as the American black vulture, Mexican vulture, zopilote, urubu, or gallinazo, is a bird in the New World vulture family whose range extends from the northeastern United States to Peru, Central Chile and Uruguay in South America. Although a common and widespread species, it has a somewhat more restricted distribution than its compatriot, the turkey vulture, which breeds well into Canada and south to Tierra del Fuego. It is the only extant member of the genus Coragyps, which is in the family Cathartidae. Despite the similar name and appearance, this species is unrelated to the Eurasian black vulture, an Old World vulture in the family Accipitridae. It inhabits relatively open areas which provide scattered forests or shrublands. With a wingspan of 1.5 m (4.9 ft), the black vulture is a large bird, though relatively small for a vulture. It has black plumage, a featherless, grayish-black head and neck, and a short, hooked beak.

The California condor is a New World vulture and the largest North American land bird. It became extinct in the wild in 1987 when all remaining wild individuals were captured, but has since been reintroduced to northern Arizona and southern Utah, the coastal mountains of California, and northern Baja California in Mexico. Although four other fossil members are known, it is the only surviving member of the genus Gymnogyps. The species is listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as Critically Endangered, and similarly considered Critically Imperiled by NatureServe.

The Andean condor is a giant South American Cathartid vulture and is the only member of the genus Vultur. Found in the Andes mountains and adjacent Pacific coasts of western South America, the Andean condor is the largest flying bird in the world by combined measurement of weight and wingspan. It has a maximum wingspan of 3.3 m and weight of 15 kg (33 lb). It is generally considered as the largest bird of prey in the world.

The king vulture is a large bird found in Central and South America. It is a member of the New World vulture family Cathartidae. This vulture lives predominantly in tropical lowland forests stretching from southern Mexico to northern Argentina. It is the only surviving member of the genus Sarcoramphus, although fossil members are known.

The black geese of the genus Branta are waterfowl belonging to the true geese and swans subfamily Anserinae. They occur in the northern coastal regions of the Palearctic and all over North America, migrating to more southernly coasts in winter, and as resident birds in the Hawaiian Islands. Alone in the Southern Hemisphere, a self-sustaining feral population derived from introduced Canada geese is also found in New Zealand.

The New Zealand swan is an extinct indigenous swan from the Chatham Islands and the South Island of New Zealand. Discovered as archaeological remains in 1889, it was originally considered a separate species from the Australian black swan because of its slightly larger bones, and swans not having been introduced to New Zealand until 1864. From 1998 until 2017, it was considered to be simply a New Zealand population of Cygnus atratus, until DNA recovered from fossil bones determined that it was indeed a separate species, much larger and heavier than its Australian relative.

Coragyps is a genus of New World vulture that contains the black vulture (Coragyps atratus) and two extinct relatives.

The thick-billed parrots are stocky brilliant green Neotropical parrots with heavy black beaks of genus Rhynchopsitta of thick billed macaw-like parrots. The genus comprises two extant species, the thick-billed parrot and the maroon-fronted parrot, as well as an extinct species from the Late Pleistocene in Mexico. The two extant taxa were formerly considered conspecific; they have become rare and are restricted to a few small areas in northern Mexico. The range of the thick-billed parrot formerly extended into the southwestern United States; attempts at reintroduction have been unsuccessful so far.

Mycteria is a genus of large tropical storks with representatives in the Americas, east Africa and southern and southeastern Asia. Two species have "ibis" in their scientific or old common names, but they are not related to these birds and simply look more similar to an ibis than do other storks.

Ciconia is a genus of birds in the stork family. Six of the seven living species occur in the Old World, but the maguari stork has a South American range. In addition, fossils suggest that Ciconia storks were somewhat more common in the tropical Americas in prehistoric times.

Chendytes lawi is an extinct, goose-sized flightless marine duck, once common on the California coast, the California Channel Islands, and possibly southern Oregon. It lived in the Pleistocene and survived into the Holocene. It appears to have gone extinct at about 450–250 BCE. The youngest direct radiocarbon date from a Chendytes bone fragment dates to 770–400 BCE and was found in an archeological site in Ventura County. Its remains have been found in fossil deposits and in early coastal archeological sites. Archeological data from coastal California show a record of human exploitation of Chendytes lawi for at least 8,000 years. It was probably driven to extinction by hunting, animal predation, and loss of habitat. Chendytes bones have been identified in archaeological assemblages from 14 coastal sites, including two on San Miguel Island and 12 in mainland localities. Hundreds of Chendytes bones and egg shells found in Pleistocene deposits on San Miguel Island have been interpreted as evidence that some of these island fossil localities were nesting colonies, one of which Guthrie dated to about 12,000 14C years. There is nothing in the North American archaeological record indicating a span of exploitation for any megafaunal genus remotely as long as that of Chendytes.

Teratornis was a genus of huge North American birds of prey—the best-known of the teratorns—of which, two species are known to have existed: Teratornis merriami and Teratornis woodburnensis. A large number of fossil and subfossil bones, representing more than 100 individuals, have been found in locations in California, Oregon, southern Nevada, Arizona, and Florida, though most are from the Californian La Brea Tar Pits. All remains except one Early Pleistocene partial skeleton from the Leisey Shell Pit near Charlotte Harbor, Florida date from the Late Pleistocene, with the youngest remains dating from the Pleistocene–Holocene boundary.

Burnet Cave is an important archaeological and paleontological site located in Eddy County, New Mexico, United States within the Guadalupe Mountains about 26 miles west of Carlsbad.

Desmodus draculae is an extinct species of vampire bat that inhabited Central and South America during the Pleistocene, and possibly the early Holocene. It was 30% larger than its living relative the common vampire bat. Fossils and unmineralized subfossils have been found in Argentina, Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Venezuela, Belize, and Bolivia.

Cathartornis is an ancient bird of the Teratornithidae family. It lived somewhere between 23 million years and 10,000 years ago. The only evidence of the bird's existence is a few bones. Its remains were documented in 1910. Cathartornis was described on the basis of 2 tarsometatarsi, 1 complete and 1 containing only the distal end, recovered from the Pleistocene La Brea Tar Pits in Southern California. Since then, no other fossils have officially been referred to the taxon, though some fossils assigned to Teratornis could be from Cathartornis and unpublished remains have been mentioned.

Buteogallus daggetti, occasionally called "Daggett's eagle" or the "walking eagle", is an extinct species of long-legged hawk which lived in southwest North America during the Pleistocene. Initially believed to be some sort of carrion-eating eagle, it was for some time placed in the distinct genus Wetmoregyps, named for Alexander Wetmore. It probably resembled a larger version of the modern-day savanna hawk, with its long legs possibly used like the secretarybird of Africa to hunt for small reptiles from a safe distance. It died out about 13,000 years ago.

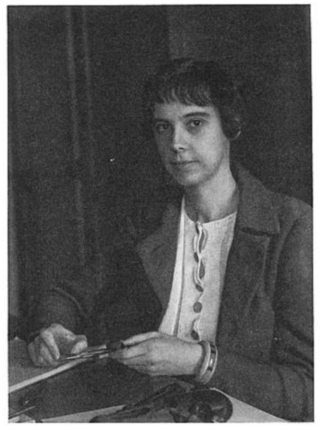

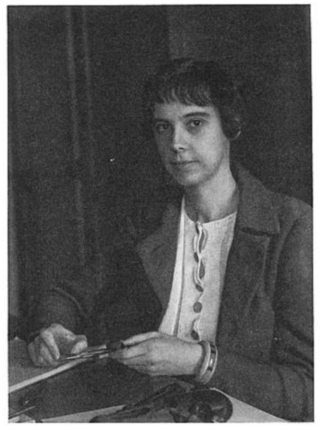

Hildegarde Howard was an American pioneer in paleornithology, mentored by the famous ornithologist, Joseph Grinnell, at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) and in avian paleontology. She was well known for her discoveries in the La Brea Tar Pits, among them the Rancho La Brea eagles. She also discovered and described Pleistocene flightless waterfowl at the prehistoric Ballona wetlands of coastal Los Angeles County at Playa del Rey. In 1953, Howard became the third woman to be awarded the Brewster Medal. She was also the first woman president of the Southern California Academy of Sciences. Hildegarde, throughout her career wrote 150 papers.

A list of prehistoric and extinct species whose fossils have been found in the La Brea Tar Pits, located in present-day Hancock Park, a city park on the Miracle Mile section of the Mid-Wilshire district in Los Angeles, California.