Related Research Articles

The Ides of March is the day on the Roman calendar marked as the Idus, roughly the midpoint of a month, of Martius, corresponding to 15 March on the Gregorian calendar. It was marked by several major religious observances. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

Jupiter, also known as Jove, is the god of the sky and thunder, and king of the gods in ancient Roman religion and mythology. Jupiter was the chief deity of Roman state religion throughout the Republican and Imperial eras, until Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire. In Roman mythology, he negotiates with Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, to establish principles of Roman religion such as offering, or sacrifice.

In Roman religion, Angerona or Angeronia was an old Roman goddess, whose name and functions are variously explained. She is sometimes identified with the goddess Feronia.

In ancient Roman religion, Dius Fidius was a god of oaths associated with Jupiter. His name was thought to be related to Fides.

In ancient Roman religion, the diiNovensiles or Novensides are collective deities of obscure significance found in inscriptions, prayer formulary, and both ancient and early-Christian literary texts.

In ancient Roman religion, Sancus was a god of trust, honesty, and oaths. His cult, one of the most ancient amongst the Romans, probably derived from Umbrian influences. Cato and Silius Italicus wrote that Sancus was a Sabine god and father of the eponymous Sabine hero Sabus. He is thus sometimes considered a founder-deity.

Neptune is the god of freshwater and the sea in the Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. In the Greek-inspired tradition, he is a brother of Jupiter and Pluto, with whom preside over the realms of heaven, the earthly world, and the seas. Salacia is his wife.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces. The month of January is named for Janus (Ianuarius). According to ancient Roman farmers' almanacs, Juno was mistaken as the tutelary deity of the month of January, but Juno is the tutelary deity of the month of June.

Juno was an ancient Roman goddess, the protector and special counsellor of the state. She was equated to Hera, queen of the gods in Greek mythology and a goddess of love and marriage. A daughter of Saturn and Ops, she was the sister and wife of Jupiter and the mother of Mars, Vulcan, Bellona, Lucina and Juventas. Like Hera, her sacred animal was the peacock. Her Etruscan counterpart was Uni, and she was said to also watch over the women of Rome. As the patron goddess of Rome and the Roman Empire, Juno was called Regina ("Queen") and was a member of the Capitoline Triad, centered on the Capitoline Hill in Rome, and also including Jupiter, and Minerva, goddess of wisdom.

In ancient Roman religion and mythology, Tellus Mater or Terra Mater is the personification of the Earth. Although Tellus and Terra are hardly distinguishable during the Imperial era, Tellus was the name of the original earth goddess in the religious practices of the Republic or earlier. The scholar Varro (1st century BC) lists Tellus as one of the di selecti, the twenty principal gods of Rome, and one of the twelve agricultural deities. She is regularly associated with Ceres in rituals pertaining to the earth and agricultural fertility.

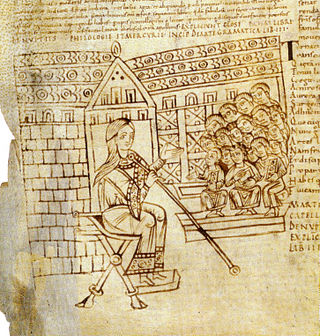

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a native of Madaura.

Caelus or Coelus was a primordial god of the sky in Roman mythology and theology, iconography, and literature. The deity's name usually appears in masculine grammatical form when he is conceived of as a male generative force.

Aion is a Hellenistic deity associated with time, the orb or circle encompassing the universe, and the zodiac. The "time" which Aion represents is perpetual, unbounded, ritual, and cyclic: The future is a returning version of the past, later called aevum. This kind of time contrasts with empirical, linear, progressive, and historical time that Chronos represented, which divides into past, present, and future.

Vettius Agorius Praetextatus was a wealthy pagan aristocrat in the 4th-century Roman Empire, and a high priest in the cults of numerous gods. He served as the praetorian prefect at the court of Emperor Valentinian II in 384 until his death that same year.

Greco-Roman mythology features male homosexuality in many of the constituent myths. In addition, there are instances of cross-dressing, androgyny, and other themes which are grouped under the acronym LGBTQ+.

Granius Flaccus was an antiquarian and scholar of Roman law and religion, probably in the time of Julius Caesar and Augustus.

In ancient Roman religion, the indigitamenta were lists of deities kept by the College of Pontiffs to assure that the correct divine names were invoked for public prayers. These lists or books probably described the nature of the various deities who might be called on under particular circumstances, with specifics about the sequence of invocation. The earliest indigitamenta, like many other aspects of Roman religion, were attributed to Numa Pompilius, second king of Rome.

The supplicia canum was an annual sacrifice of ancient Roman religion in which live dogs were suspended from a furca ("fork") or cross (crux) and paraded. It appears on none of the extant Roman calendars, but a late source places it on August 3 (III Non. Aug.).

Tarquitius Priscus was a Roman writer of Etruscan heritage, known for works on the etrusca disciplina, the body of knowledge pertaining to Etruscan religion and cosmology.

References

- ↑ C. Robert Phillips III, "Approaching Roman Religion: The Case for Wissenschaftsgeschichte," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 15, citing HLL 4.78; Robert Lamberton, Homer the Theologian: Neoplatonist Allegorical Reading and the Growth of the Epic Tradition (University of California Press, 1986), p. 250.

- ↑ Attilio Mastrocinque, "Creating One's Own Religion: Intellectual Choices," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 384.

- ↑ Mastrocinque, "Creating One's Own Religion," p. 384; R. Majercik, "Chaldean Triads in Neoplatonic Exegesis: Some Reconsiderations," Classical Quarterly 51.1 (2002), p. 291, note 119, citing P. Mastandrea, Un Neoplatonico Latino: Cornelio Labeone (Leiden, 1979), 127–34 and 193–8; Robert A. Kaster, Studies on the Text of Macrobius' Saturnalia (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 39; Lamberton, Homer the Theologian, p. 249 (where he is ranked among "the Latin authors of greatest importance for the development of Platonism in late antiquity").

- 1 2 3 Phillips, "Approaching Roman Religion," p. 15.

- ↑ Clifford Ando, "The Palladium and the Pentateuch: Towards a Sacred Topography of the Later Roman Empire," Phoenix 55 (2001), pp. 402–403, and The Matter of the Gods: Religion and the Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2008), p. 193. Alan Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 267, considers Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.17–23 as "nothing but a series of excerpts from Labeo."

- ↑ Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome, p. 268, noting that Lydus excerpted many of the same passages from Labeo as Macrobius did.

- ↑ Phillips, "Approaching Roman Religion," p. 15. Example at note to Aeneid 3.168.

- ↑ R. Delbrueck and W. Vollgraff, "An Orphic Bowl," Journal of Hellenic Studies 54 (1934), p. 134.

- ↑ Arnobius 2.15.

- ↑ Augustine, De civitate Dei 2.11, 9.19.

- ↑ Majercik, "Chaldean Triads in Neoplatonic Exegesis," p. 291, note 119, citing Mastandrea, Un Neoplatonico Latino, 127–34 and 193–8.

- ↑ Gérard Capdeville, "Les dieux de Martianus Capella," Revue de l'histoire des religions 213.3 (1996), p. 258, note 18, citing Robert Turcan, "Martianus Capella et Jamblique," REL 36 (1958) 235–254. On the difficulty of determining Macrobius's use of Labeo, see Danuta Shanzer, A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella's De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, Book 1 (University of California Press, 1986), pp. 133–138, 193–194.

- 1 2 Lambertson, Homer the Theologian, p. 250.

- ↑ Augustine, De civitate Dei 2.11, 8.22, 3.25; Maijastina Kahlos, Debate and Dialogue: Christian and Pagan Cultures c. 360–430 (Ashgate, 2007), p. 175.

- ↑ Kahlos, Debate and Dialogue, p. 157.

- ↑ Lydus, De mensibus 1.21, 3.1.12, 3.10.

- ↑ Hendrik H.J. Brouwer, Bona Dea: The Sources and a Description of the Cult (Brill, 1989) p. 224.

- ↑ Macobius, Saturnalia 1.18.18–21; Polymnia Athanassiadi and Michael Frede, introduction to Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 16, citing Tübingen Theosophy 12.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.18.20.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.18.19.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer, Judeophobia: Attitudes toward the Jews in the Ancient World (Harvard University Press, 1997, 1998), p. 52.

- ↑ Ramsay MacMullen, Paganism in the Roman Empire (Yale University Press, 1981), p. 87.

- ↑ The name of the Jewish god is first given as Iao by Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica 1.94.2 (1st century BC) and Varro (as preserved by Lydus, De mensibus 4.53). As a Jewish term it is attested by the Aramaic papyri from Elephantine dating to the Persian period. Assumed to have become a vocabulum ineffabile for Jews, it occurs in a fragment of the Septuagint version of Leviticus probably dating to the 1st century BC, but it does not occur in the textus receptus of the Septuagint. The name is ubiquitous in magic texts from all over the Greco-Roman world, an indication that it had passed out of "official" usage and become popularized by syncretism. See Peter Schäfer, Judeophobia pp. 53, 232, and Hugo Rahner, Greek Myths and Christian Mystery (Burns & Oak, 1963, reprinted 1971, originally published 1957 in German), p. 146, citing also R. Ganschinietz, "Jao," in RE 9, col. 708, 1–33. See also John Granger Cook, The Interpretation of the Old Testament in Greco-Roman Paganism (Mohr Siebeck, 2004), p. 118.

- ↑ Schäfer, Judeophobia, p. 53.

- ↑ "Wrongly" as noted by Stefan Weinstock, "Libri fulgurales," Papers of the British School at Rome 19 (1951), p. 138.