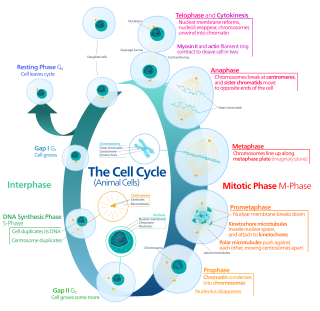

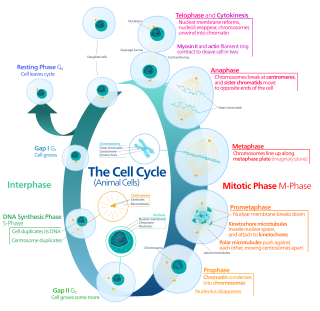

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA and some of its organelles, and subsequently the partitioning of its cytoplasm, chromosomes and other components into two daughter cells in a process called cell division.

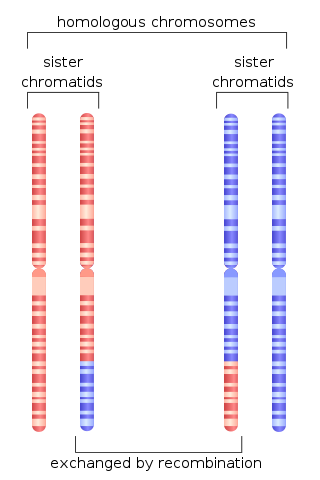

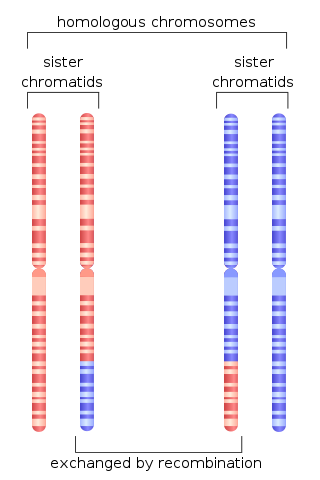

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there are two distinct types of cell division: a vegetative division (mitosis), producing daughter cells genetically identical to the parent cell, and a cell division that produces haploid gametes for sexual reproduction (meiosis), reducing the number of chromosomes from two of each type in the diploid parent cell to one of each type in the daughter cells. In Mitosis is a part of the cell cycle, in which, replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is maintained. In general, mitosis is preceded by the S stage of interphase and is followed by telophase and cytokinesis; which divides the cytoplasm, organelles, and cell membrane of one cell into two new cells containing roughly equal shares of these cellular components. The different stages of mitosis all together define the M phase of an animal cell cycle—the division of the mother cell into two genetically identical daughter cells. To ensure proper progression through the cell cycle, DNA damage is detected and repaired at various checkpoints throughout the cycle. These checkpoints can halt progression through the cell cycle by inhibiting certain cyclin-CDK complexes. Meiosis undergoes two divisions resulting in four haploid daughter cells. Homologous chromosomes are separated in the first division of meiosis, such that each daughter cell has one copy of each chromosome. These chromosomes have already been replicated and have two sister chromatids which are then separated during the second division of meiosis. Both of these cell division cycles are used in the process of sexual reproduction at some point in their life cycle. Both are believed to be present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor.

Interphase is the portion of the cell cycle that is not accompanied by visible changes under the microscope, and includes the G1, S and G2 phases. During interphase, the cell grows (G1), replicates its DNA (S) and prepares for mitosis (G2). A cell in interphase is not simply quiescent. The term quiescent would be misleading since a cell in interphase is very busy synthesizing proteins, copying DNA into RNA, engulfing extracellular material, processing signals, to name just a few activities. The cell is quiescent only in the sense of cell division. Interphase is the phase of the cell cycle in which a typical cell spends most of its life. Interphase is the 'daily living' or metabolic phase of the cell, in which the cell obtains nutrients and metabolizes them, grows, replicates its DNA in preparation for mitosis, and conducts other "normal" cell functions.

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encodes its genome. In human cells, both normal metabolic activities and environmental factors such as radiation can cause DNA damage, resulting in tens of thousands of individual molecular lesions per cell per day. Many of these lesions cause structural damage to the DNA molecule and can alter or eliminate the cell's ability to transcribe the gene that the affected DNA encodes. Other lesions induce potentially harmful mutations in the cell's genome, which affect the survival of its daughter cells after it undergoes mitosis. As a consequence, the DNA repair process is constantly active as it responds to damage in the DNA structure. When normal repair processes fail, and when cellular apoptosis does not occur, irreparable DNA damage may occur, including double-strand breaks and DNA crosslinkages. This can eventually lead to malignant tumors, or cancer as per the two hit hypothesis.

S phase (Synthesis phase) is the phase of the cell cycle in which DNA is replicated, occurring between G1 phase and G2 phase. Since accurate duplication of the genome is critical to successful cell division, the processes that occur during S-phase are tightly regulated and widely conserved.

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is a pathway that repairs double-strand breaks in DNA. It is called "non-homologous" because the break ends are directly ligated without the need for a homologous template, in contrast to homology directed repair (HDR), which requires a homologous sequence to guide repair. NHEJ is active in both non-dividing and proliferating cells, while HDR is not readily accessible in non-dividing cells. The term "non-homologous end joining" was coined in 1996 by Moore and Haber.

G2 phase, Gap 2 phase, or Growth 2 phase, is the third subphase of interphase in the cell cycle directly preceding mitosis. It follows the successful completion of S phase, during which the cell’s DNA is replicated. G2 phase ends with the onset of prophase, the first phase of mitosis in which the cell’s chromatin condenses into chromosomes.

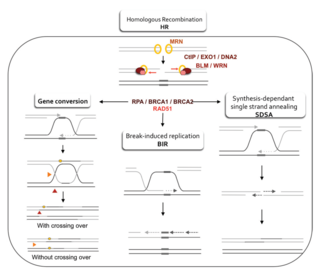

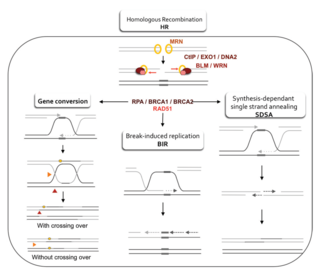

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids.

Cell cycle checkpoints are control mechanisms in the eukaryotic cell cycle which ensure its proper progression. Each checkpoint serves as a potential termination point along the cell cycle, during which the conditions of the cell are assessed, with progression through the various phases of the cell cycle occurring only when favorable conditions are met. There are many checkpoints in the cell cycle, but the three major ones are: the G1 checkpoint, also known as the Start or restriction checkpoint or Major Checkpoint; the G2/M checkpoint; and the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, also known as the spindle checkpoint. Progression through these checkpoints is largely determined by the activation of cyclin-dependent kinases by regulatory protein subunits called cyclins, different forms of which are produced at each stage of the cell cycle to control the specific events that occur therein.

Ku is a dimeric protein complex that binds to DNA double-strand break ends and is required for the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway of DNA repair. Ku is evolutionarily conserved from bacteria to humans. The ancestral bacterial Ku is a homodimer. Eukaryotic Ku is a heterodimer of two polypeptides, Ku70 (XRCC6) and Ku80 (XRCC5), so named because the molecular weight of the human Ku proteins is around 70 kDa and 80 kDa. The two Ku subunits form a basket-shaped structure that threads onto the DNA end. Once bound, Ku can slide down the DNA strand, allowing more Ku molecules to thread onto the end. In higher eukaryotes, Ku forms a complex with the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) to form the full DNA-dependent protein kinase, DNA-PK. Ku is thought to function as a molecular scaffold to which other proteins involved in NHEJ can bind, orienting the double-strand break for ligation.

Cyclin A is a member of the cyclin family, a group of proteins that function in regulating progression through the cell cycle. The stages that a cell passes through that culminate in its division and replication are collectively known as the cell cycle Since the successful division and replication of a cell is essential for its survival, the cell cycle is tightly regulated by several components to ensure the efficient and error-free progression through the cell cycle. One such regulatory component is cyclin A which plays a role in the regulation of two different cell cycle stages.

Tumor suppressor p53-binding protein 1 also known as p53-binding protein 1 or 53BP1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TP53BP1 gene.

Homology-directed repair (HDR) is a mechanism in cells to repair double-strand DNA lesions. The most common form of HDR is homologous recombination. The HDR mechanism can only be used by the cell when there is a homologous piece of DNA present in the nucleus, mostly in G2 and S phase of the cell cycle. Other examples of homology-directed repair include single-strand annealing and breakage-induced replication. When the homologous DNA is absent, another process called non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) takes place instead.

The MRX complex is a heterotrimeric protein complex consisting of Mre11, Rad50, and Xrs2. It is a budding yeast homolog of the mammalian Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) DNA damage repair complex.

Microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), also known as alternative nonhomologous end-joining (Alt-NHEJ) is one of the pathways for repairing double-strand breaks in DNA. As reviewed by McVey and Lee, the foremost distinguishing property of MMEJ is the use of microhomologous sequences during the alignment of broken ends before joining, thereby resulting in deletions flanking the original break. MMEJ is frequently associated with chromosome abnormalities such as deletions, translocations, inversions and other complex rearrangements.

The G2-M DNA damage checkpoint is an important cell cycle checkpoint in eukaryotic organisms that ensures that cells don't initiate mitosis until damaged or incompletely replicated DNA is sufficiently repaired. Cells with a defective G2-M checkpoint will undergo apoptosis or death after cell division if they enter the M phase before repairing their DNA. The defining biochemical feature of this checkpoint is the activation of M-phase cyclin-CDK complexes, which phosphorylate proteins that promote spindle assembly and bring the cell to metaphase.

Shelterin is a protein complex known to protect telomeres in many eukaryotes from DNA repair mechanisms, as well as to regulate telomerase activity. In mammals and other vertebrates, telomeric DNA consists of repeating double-stranded 5'-TTAGGG-3' (G-strand) sequences along with the 3'-AATCCC-5' (C-strand) complement, ending with a 50-400 nucleotide 3' (G-strand) overhang. Much of the final double-stranded portion of the telomere forms a T-loop (Telomere-loop) that is invaded by the 3' (G-strand) overhang to form a small D-loop (Displacement-loop).

Cell cycle withdrawal refers to the natural stoppage of cell cycle during cell division. When cells divide, there are many internal or external factors that would lead to a stoppage of division. This stoppage could be permanent or temporary, and could occur in any one of the four cycle phases, depending on the status of cells or the activities they are undergoing. During the process, all cell duplication process, including mitosis, meiosis as well as DNA replication, will be paused. The mechanisms involve the proteins and DNA sequences inside cells.

Telomeres, the caps on the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes, play critical roles in cellular aging and cancer. An important facet to how telomeres function in these roles is their involvement in cell cycle regulation.

A double-strand break repair model refers to the various models of pathways that cells undertake to repair double strand-breaks (DSB). DSB repair is an important cellular process, as the accumulation of unrepaired DSB could lead to chromosomal rearrangements, tumorigenesis or even cell death. In human cells, there are two main DSB repair mechanisms: Homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). HR relies on undamaged template DNA as reference to repair the DSB, resulting in the restoration of the original sequence. NHEJ modifies and ligates the damaged ends regardless of homology. In terms of DSB repair pathway choice, most mammalian cells appear to favor NHEJ rather than HR. This is because the employment of HR may lead to gene deletion or amplification in cells which contains repetitive sequences. In terms of repair models in the cell cycle, HR is only possible during the S and G2 phases, while NHEJ can occur throughout whole process. These repair pathways are all regulated by the overarching DNA damage response mechanism. Besides HR and NHEJ, there are also other repair models which exists in cells. Some are categorized under HR, such as synthesis-dependent strain annealing, break-induced replication, and single-strand annealing; while others are an entirely alternate repair model, namely, the pathway microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ).