In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is their cell envelope, which consists of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall sandwiched between an inner (cytoplasmic) membrane and an outer membrane. These bacteria are found in all environments that support life on Earth.

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating residues of β-(1,4) linked N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM). Attached to the N-acetylmuramic acid is an oligopeptide chain made of three to five amino acids. The peptide chain can be cross-linked to the peptide chain of another strand forming the 3D mesh-like layer. Peptidoglycan serves a structural role in the bacterial cell wall, giving structural strength, as well as counteracting the osmotic pressure of the cytoplasm. This repetitive linking results in a dense peptidoglycan layer which is critical for maintaining cell form and withstanding high osmotic pressures, and it is regularly replaced by peptidoglycan production. Peptidoglycan hydrolysis and synthesis are two processes that must occur in order for cells to grow and multiply, a technique carried out in three stages: clipping of current material, insertion of new material, and re-crosslinking of existing material to new material.

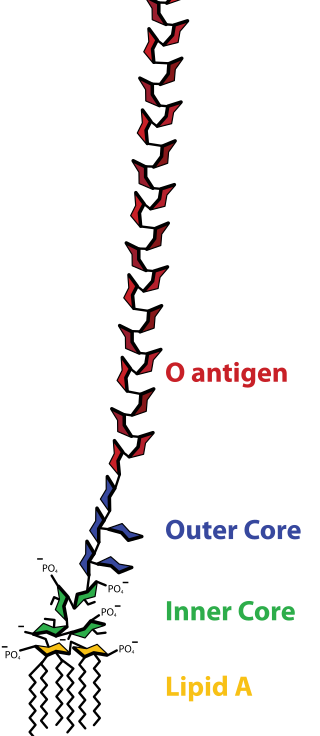

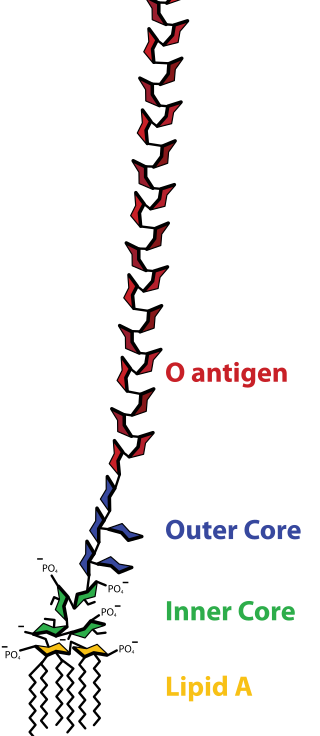

Lipopolysaccharide, now more commonly known as endotoxin, is a collective term for components of the outermost membrane of cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli and Salmonella with a common structural architecture. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of three parts: an outer core polysaccharide termed the O-antigen, an inner core oligosaccharide and Lipid A, all covalently linked. In current terminology, the term endotoxin is often used synonymously with LPS, although there are a few endotoxins that are not related to LPS, such as the so-called delta endotoxin proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis.

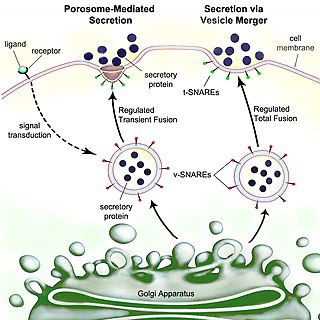

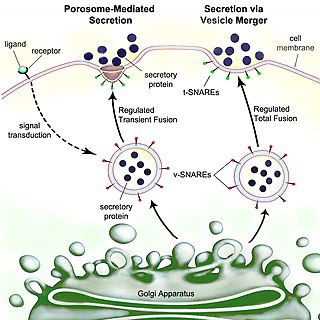

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical mechanism of cell secretion is via secretory portals at the plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structures embedded in the cell membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

The periplasm is a concentrated gel-like matrix in the space between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the bacterial outer membrane called the periplasmic space in Gram-negative bacteria. Using cryo-electron microscopy it has been found that a much smaller periplasmic space is also present in Gram-positive bacteria, between cell wall and the plasma membrane. The periplasm may constitute up to 40% of the total cell volume of gram-negative bacteria, but is a much smaller percentage in gram-positive bacteria.

The cell envelope comprises the inner cell membrane and the cell wall of a bacterium. In Gram-negative bacteria an outer membrane is also included. This envelope is not present in the Mollicutes where the cell wall is absent.

Polymyxins are antibiotics. Polymyxins B and E are used in the treatment of Gram-negative bacterial infections. They work mostly by breaking up the bacterial cell membrane. They are part of a broader class of molecules called nonribosomal peptides.

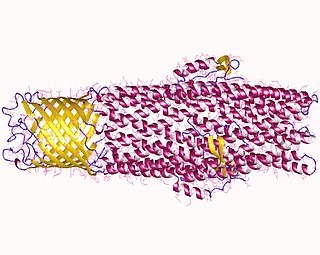

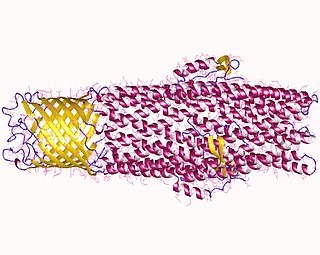

Porins are beta barrel proteins that cross a cellular membrane and act as a pore, through which molecules can diffuse. Unlike other membrane transport proteins, porins are large enough to allow passive diffusion, i.e., they act as channels that are specific to different types of molecules. They are present in the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria and some gram-positive mycobacteria, the outer membrane of mitochondria, and the outer chloroplast membrane.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), also called host defence peptides (HDPs) are part of the innate immune response found among all classes of life. Fundamental differences exist between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells that may represent targets for antimicrobial peptides. These peptides are potent, broad spectrum antimicrobials which demonstrate potential as novel therapeutic agents. Antimicrobial peptides have been demonstrated to kill Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria, enveloped viruses, fungi and even transformed or cancerous cells. Unlike the majority of conventional antibiotics it appears that antimicrobial peptides frequently destabilize biological membranes, can form transmembrane channels, and may also have the ability to enhance immunity by functioning as immunomodulators.

The bacterial outer membrane is found in gram-negative bacteria. Gram-negative bacteria form two lipid bilayers in their cell envelopes - an inner membrane (IM) that encapsulates the cytoplasm, and an outer membrane (OM) that encapsulates the periplasm.

A bacterium, despite its simplicity, contains a well-developed cell structure which is responsible for some of its unique biological structures and pathogenicity. Many structural features are unique to bacteria and are not found among archaea or eukaryotes. Because of the simplicity of bacteria relative to larger organisms and the ease with which they can be manipulated experimentally, the cell structure of bacteria has been well studied, revealing many biochemical principles that have been subsequently applied to other organisms.

Virulence factors are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens to achieve the following:

An efflux pump is an active transporter in cells that moves out unwanted material. Efflux pumps are an important component in bacteria in their ability to remove antibiotics. The efflux could also be the movement of heavy metals, organic pollutants, plant-produced compounds, quorum sensing signals, bacterial metabolites and neurotransmitters. All microorganisms, with a few exceptions, have highly conserved DNA sequences in their genome that encode efflux pumps. Efflux pumps actively move substances out of a microorganism, in a process known as active efflux, which is a vital part of xenobiotic metabolism. This active efflux mechanism is responsible for various types of resistance to bacterial pathogens within bacterial species - the most concerning being antibiotic resistance because microorganisms can have adapted efflux pumps to divert toxins out of the cytoplasm and into extracellular media.

Lysins, also known as endolysins or murein hydrolases, are hydrolytic enzymes produced by bacteriophages in order to cleave the host's cell wall during the final stage of the lytic cycle. Lysins are highly evolved enzymes that are able to target one of the five bonds in peptidoglycan (murein), the main component of bacterial cell walls, which allows the release of progeny virions from the lysed cell. Cell-wall-containing Archaea are also lysed by specialized pseudomurein-cleaving lysins, while most archaeal viruses employ alternative mechanisms. Similarly, not all bacteriophages synthesize lysins: some small single-stranded DNA and RNA phages produce membrane proteins that activate the host's autolytic mechanisms such as autolysins.

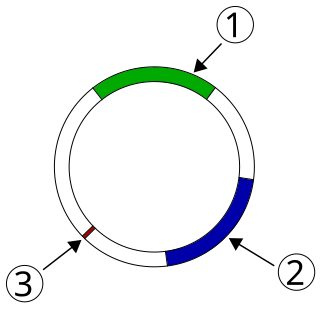

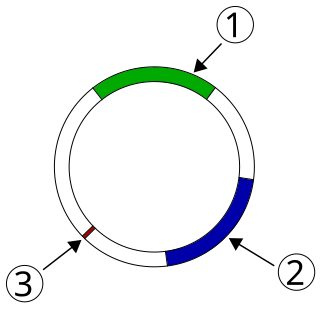

Plasmid-mediated resistance is the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes which are carried on plasmids. Plasmids possess mechanisms that ensure their independent replication as well as those that regulate their replication number and guarantee stable inheritance during cell division. By the conjugation process, they can stimulate lateral transfer between bacteria from various genera and kingdoms. Numerous plasmids contain addiction-inducing systems that are typically based on toxin-antitoxin factors and capable of killing daughter cells that don't inherit the plasmid during cell division. Plasmids often carry multiple antibiotic resistance genes, contributing to the spread of multidrug-resistance (MDR). Antibiotic resistance mediated by MDR plasmids severely limits the treatment options for the infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria, especially family Enterobacteriaceae. The global spread of MDR plasmids has been enhanced by selective pressure from antimicrobial medications used in medical facilities and when raising animals for food.

Omptins are a family of bacterial proteases. They are aspartate proteases, which cleave peptides with the use of a water molecule. Found in the outer membrane of gram-negative enterobacteria such as Shigella flexneri, Yersinia pestis, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella enterica. Omptins consist of a widely conserved beta barrel spanning the membrane with 5 extracellular loops. These loops are responsible for the various substrate specificities. These proteases rely upon binding of lipopolysaccharide for activity.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) are gram-negative bacteria that are resistant to the carbapenem class of antibiotics, considered the drugs of last resort for such infections. They are resistant because they produce an enzyme called a carbapenemase that disables the drug molecule. The resistance can vary from moderate to severe. Enterobacteriaceae are common commensals and infectious agents. Experts fear CRE as the new "superbug". The bacteria can kill up to half of patients who get bloodstream infections. Tom Frieden, former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has referred to CRE as "nightmare bacteria". Examples of enzymes found in certain types of CRE are KPC and NDM. KPC and NDM are enzymes that break down carbapenems and make them ineffective. Both of these enzymes, as well as the enzyme VIM have also been reported in Pseudomonas.

Teixobactin is a peptide-like secondary metabolite of some species of bacteria, that kills some gram-positive bacteria. It appears to belong to a new class of antibiotics, and harms bacteria by binding to lipid II and lipid III, important precursor molecules for forming the cell wall.

The type 2 secretion system is a type of protein secretion machinery found in various species of Gram-negative bacteria, including many human pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio cholerae. The type II secretion system is one of six protein secretory systems commonly found in Gram-negative bacteria, along with the type I, type III, and type IV secretion systems, as well as the chaperone/usher pathway, the autotransporter pathway/type V secretion system, and the type VI secretion system. Like these other systems, the type II secretion system enables the transport of cytoplasmic proteins across the lipid bilayers that make up the cell membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Secretion of proteins and effector molecules out of the cell plays a critical role in signaling other cells and in the invasion and parasitism of host cells.