A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between atoms or ions that enables the formation of molecules and crystals. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds, or through the sharing of electrons as in covalent bonds. The strength of chemical bonds varies considerably; there are "strong bonds" or "primary bonds" such as covalent, ionic and metallic bonds, and "weak bonds" or "secondary bonds" such as dipole–dipole interactions, the London dispersion force and hydrogen bonding. Strong chemical bonding arises from the sharing or transfer of electrons between the participating atoms.

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons, is known as covalent bonding. For many molecules, the sharing of electrons allows each atom to attain the equivalent of a full valence shell, corresponding to a stable electronic configuration. In organic chemistry, covalent bonding is much more common than ionic bonding.

Ionic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that involves the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions, or between two atoms with sharply different electronegativities, and is the primary interaction occurring in ionic compounds. It is one of the main types of bonding, along with covalent bonding and metallic bonding. Ions are atoms with an electrostatic charge. Atoms that gain electrons make negatively charged ions. Atoms that lose electrons make positively charged ions. This transfer of electrons is known as electrovalence in contrast to covalence. In the simplest case, the cation is a metal atom and the anion is a nonmetal atom, but these ions can be of a more complex nature, e.g. molecular ions like NH+

4 or SO2−

4. In simpler words, an ionic bond results from the transfer of electrons from a metal to a non-metal in order to obtain a full valence shell for both atoms.

Metallic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that arises from the electrostatic attractive force between conduction electrons and positively charged metal ions. It may be described as the sharing of free electrons among a structure of positively charged ions (cations). Metallic bonding accounts for many physical properties of metals, such as strength, ductility, thermal and electrical resistivity and conductivity, opacity, and luster.

In theoretical chemistry, a conjugated system is a system of connected p-orbitals with delocalized electrons in a molecule, which in general lowers the overall energy of the molecule and increases stability. It is conventionally represented as having alternating single and multiple bonds. Lone pairs, radicals or carbenium ions may be part of the system, which may be cyclic, acyclic, linear or mixed. The term "conjugated" was coined in 1899 by the German chemist Johannes Thiele.

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic (ring-shaped), typically planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance that gives increased stability compared to saturated compounds having single bonds, and other geometric or connective non-cyclic arrangements with the same set of atoms. Aromatic rings are very stable and do not break apart easily. Organic compounds that are not aromatic are classified as aliphatic compounds—they might be cyclic, but only aromatic rings have enhanced stability. The term aromaticity with this meaning is historically related to the concept of having an aroma, but is a distinct property from that meaning.

The octet rule is a chemical rule of thumb that reflects the theory that main-group elements tend to bond in such a way that each atom has eight electrons in its valence shell, giving it the same electronic configuration as a noble gas. The rule is especially applicable to carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and the halogens; although more generally the rule is applicable for the s-block and p-block of the periodic table. Other rules exist for other elements, such as the duplet rule for hydrogen and helium, or the 18-electron rule for transition metals.

In chemistry, resonance, also called mesomerism, is a way of describing bonding in certain molecules or polyatomic ions by the combination of several contributing structures into a resonance hybrid in valence bond theory. It has particular value for analyzing delocalized electrons where the bonding cannot be expressed by one single Lewis structure.

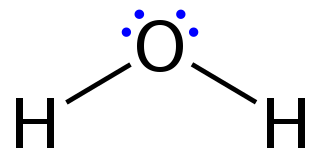

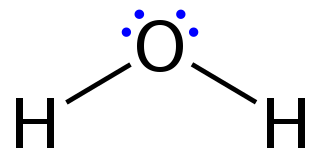

Lewis structures, also known as Lewis dot formulas,Lewis dot structures, electron dot structures, or Lewis electron dot structures (LEDS), are diagrams that show the bonding between atoms of a molecule, as well as the lone pairs of electrons that may exist in the molecule. A Lewis structure can be drawn for any covalently bonded molecule, as well as coordination compounds. The Lewis structure was named after Gilbert N. Lewis, who introduced it in his 1916 article The Atom and the Molecule. Lewis structures extend the concept of the electron dot diagram by adding lines between atoms to represent shared pairs in a chemical bond.

In chemistry, molecular orbital theory is a method for describing the electronic structure of molecules using quantum mechanics. It was proposed early in the 20th century.

In chemistry, valence bond (VB) theory is one of the two basic theories, along with molecular orbital (MO) theory, that were developed to use the methods of quantum mechanics to explain chemical bonding. It focuses on how the atomic orbitals of the dissociated atoms combine to give individual chemical bonds when a molecule is formed. In contrast, molecular orbital theory has orbitals that cover the whole molecule.

In chemistry, a hypervalent molecule is a molecule that contains one or more main group elements apparently bearing more than eight electrons in their valence shells. Phosphorus pentachloride, sulfur hexafluoride, chlorine trifluoride, the chlorite ion, and the triiodide ion are examples of hypervalent molecules.

In chemistry, orbital hybridisation is the concept of mixing atomic orbitals to form new hybrid orbitals suitable for the pairing of electrons to form chemical bonds in valence bond theory. For example, in a carbon atom which forms four single bonds the valence-shell s orbital combines with three valence-shell p orbitals to form four equivalent sp3 mixtures in a tetrahedral arrangement around the carbon to bond to four different atoms. Hybrid orbitals are useful in the explanation of molecular geometry and atomic bonding properties and are symmetrically disposed in space. Usually hybrid orbitals are formed by mixing atomic orbitals of comparable energies.

In chemistry, bond order, as introduced by Linus Pauling, is defined as the difference between the number of bonds and anti-bonds.

In chemistry, a non-covalent interaction differs from a covalent bond in that it does not involve the sharing of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions between molecules or within a molecule. The chemical energy released in the formation of non-covalent interactions is typically on the order of 1–5 kcal/mol. Non-covalent interactions can be classified into different categories, such as electrostatic, π-effects, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects.

Modern valence bond theory is the application of valence bond theory [ VBT ] with computer programs that are competitive in accuracy and economy with programs for the Hartree–Fock or post-Hartree-Fock methods. The latter methods dominated quantum chemistry from the advent of digital computers because they were easier to program. The early popularity of valence bond methods thus declined. It is only recently that the programming of valence bond methods has improved. These developments are due to and described by Gerratt, Cooper, Karadakov and Raimondi (1997); Li and McWeeny (2002); Joop H. van Lenthe and co-workers (2002); Song, Mo, Zhang and Wu (2005); and Shaik and Hiberty (2004)

In chemical bonding theory, an antibonding orbital is a type of molecular orbital that weakens the chemical bond between two atoms and helps to raise the energy of the molecule relative to the separated atoms. Such an orbital has one or more nodes in the bonding region between the nuclei. The density of the electrons in the orbital is concentrated outside the bonding region and acts to pull one nucleus away from the other and tends to cause mutual repulsion between the two atoms. This is in contrast to a bonding molecular orbital, which has a lower energy than that of the separate atoms, and is responsible for chemical bonds.

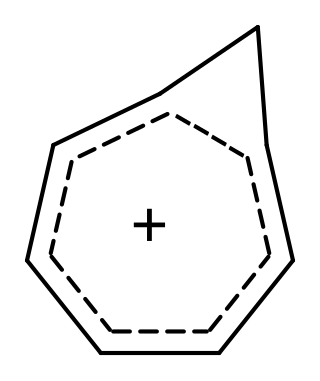

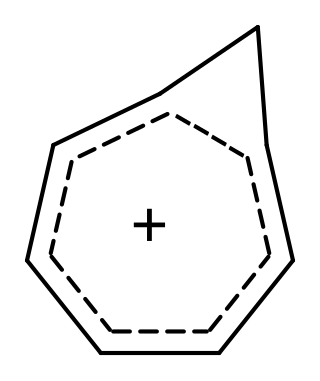

Homoaromaticity, in organic chemistry, refers to a special case of aromaticity in which conjugation is interrupted by a single sp3 hybridized carbon atom. Although this sp3 center disrupts the continuous overlap of p-orbitals, traditionally thought to be a requirement for aromaticity, considerable thermodynamic stability and many of the spectroscopic, magnetic, and chemical properties associated with aromatic compounds are still observed for such compounds. This formal discontinuity is apparently bridged by p-orbital overlap, maintaining a contiguous cycle of π electrons that is responsible for this preserved chemical stability.

In quantum chemistry, a natural bond orbital or NBO is a calculated bonding orbital with maximum electron density. The NBOs are one of a sequence of natural localized orbital sets that include "natural atomic orbitals" (NAO), "natural hybrid orbitals" (NHO), "natural bonding orbitals" (NBO) and "natural (semi-)localized molecular orbitals" (NLMO). These natural localized sets are intermediate between basis atomic orbitals (AO) and molecular orbitals (MO):

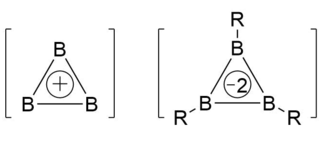

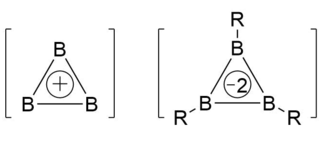

The triboracyclopropenyl fragment is a cyclic structural motif in boron chemistry, named for its geometric similarity to cyclopropene. In contrast to nonplanar borane clusters that exhibit higher coordination numbers at boron (e.g., through 3-center 2-electron bonds to bridging hydrides or cations), triboracyclopropenyl-type structures are rings of three boron atoms where substituents at each boron are also coplanar to the ring. Triboracyclopropenyl-containing compounds are extreme cases of inorganic aromaticity. They are the lightest and smallest cyclic structures known to display the bonding and magnetic properties that originate from fully delocalized electrons in orbitals of σ and π symmetry. Although three-membered rings of boron are frequently so highly strained as to be experimentally inaccessible, academic interest in their distinctive aromaticity and possible role as intermediates of borane pyrolysis motivated extensive computational studies by theoretical chemists. Beginning in the late 1980s with mass spectrometry work by Anderson et al. on all-boron clusters, experimental studies of triboracyclopropenyls were for decades exclusively limited to gas-phase investigations of the simplest rings (ions of B3). However, more recent work has stabilized the triboracyclopropenyl moiety via coordination to donor ligands or transition metals, dramatically expanding the scope of its chemistry.