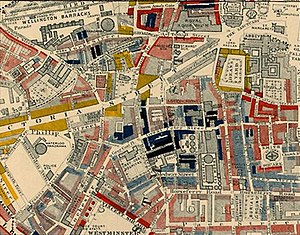

The Devil's Acre was a notorious slum near Westminster Abbey in Victorian London. [2] The Devil's Acre was on and behind Old Pye Street, Great St Anne's Lane (now St Ann's Street) and Duck Lane (now St Matthew Street) in the parish of Westminster St Margaret and St John.

A slum is a highly populated urban residential area consisting mostly of closely packed, decrepit housing units in a situation of deteriorated or incomplete infrastructure, inhabited primarily by impoverished persons. While slums differ in size and other characteristics, most lack reliable sanitation services, supply of clean water, reliable electricity, law enforcement and other basic services. Slum residences vary from shanty houses to professionally built dwellings which, because of poor-quality construction or provision of basic maintenance, have deteriorated.

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is a large, mainly Gothic abbey church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United Kingdom's most notable religious buildings and the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English and, later, British monarchs. The building itself was a Benedictine monastic church until the monastery was dissolved in 1539. Between 1540 and 1556, the abbey had the status of a cathedral. Since 1560, the building is no longer an abbey or a cathedral, having instead the status of a Church of England "Royal Peculiar"—a church responsible directly to the sovereign.

St Margaret was an ancient parish in the City and Liberty of Westminster and the county of Middlesex. It included the core of modern Westminster, including the Palace of Westminster and the area around, but not including Westminster Abbey. It was divided into St Margaret's and St John's in 1727, to coincide with the building of the Church of St John the Evangelist, constructed by the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches in Smith Square to meet the demands of the growing population, but there continued to be a single vestry for the parishes of St Margaret and St John. This was reformed in 1855 by the Metropolis Management Act, and the two parishes formed the Westminster District until 1887. St Margaret and St John became part of the County of London in 1889. The vestry was abolished in 1900, to be replaced by Westminster City Council, but St Margaret and St John continued to have a nominal existence until 1922.

Contents

In the 19th century it was considered one of the worst areas of London — in 1850 Charles Dickens called it The Devil's Acre in Household Words . In the same year the term slum was popularised by Cardinal Wiseman, based at Westminster Cathedral adjoining the area, when his description of it was widely quoted in the national press.

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era. His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime, and by the 20th century critics and scholars had recognised him as a literary genius. His novels and short stories are still widely read today.

Household Words was an English weekly magazine edited by Charles Dickens in the 1850s. It took its name from the line in Shakespeare's Henry V: "Familiar in his mouth as household words."

Westminster Cathedral, or the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ, in London is the mother church of the Catholic Church in England and Wales.