John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is a U.S. national monument in Wheeler and Grant counties in east-central Oregon. Located within the John Day River basin and managed by the National Park Service, the park is known for its well-preserved layers of fossil plants and mammals that lived in the region between the late Eocene, about 45 million years ago, and the late Miocene, about 5 million years ago. The monument consists of three geographically separate units: Sheep Rock, Painted Hills, and Clarno.

A bone bed is any geological stratum or deposit that contains bones of whatever kind. Inevitably, such deposits are sedimentary in nature. Not a formal term, it tends to be used more to describe especially dense collections such as Lagerstätte. It is also applied to brecciated and stalagmitic deposits on the floor of caves, which frequently contain osseous remains.

The Bear Gulch Limestone is a limestone-rich geological lens in central Montana, renowned for the quality of its late Mississippian-aged fossils. It is exposed over a number of outcrops northeast of the Big Snowy Mountains, and is often considered a component of the more widespread Heath Formation. The Bear Gulch Limestone reconstructs a diverse, though isolated, marine ecosystem which developed near the end of the Serpukhovian age. It is a lagerstätte, a particular type of rock unit with exceptional fossil preservation of both articulated skeletons and soft tissues. Bear Gulch fossils include a variety of fish, invertebrates, and algae occupying a number of different habitats within a preserved shallow bay.

Monte San Giorgio is a Swiss mountain and UNESCO World Heritage Site near the border between Switzerland and Italy. It is part of the Lugano Prealps, overlooking Lake Lugano in the Swiss Canton of Ticino.

Gnathorhiza is an extinct genus of prehistoric lobe-finned fish (lungfish) which lived from the Carboniferous period to the Early Triassic epoch. It is the only known lungfish genus to have crossed the Permo-Triassic boundary. Several species have been described, ranging in size from 5 to 50 centimeters.

Coahomasuchus is an extinct genus of aetosaurine aetosaur. Remains of the genus have been found from deposits in Texas and North Carolina that date to the Otischalkian faunachron of the Late Triassic. It was small for an aetosaur, being less than 1.5 metres long. The dorsal plates are distinctively flat and unflexed, and have a faint sub-parallel to radial ornamentation. The genus lacked spines or keels on these plates, features seen in many other aetosaurs. Coahomasuchus was very similar in appearance to the closely related Aetosaurus.

Sangusaurus is an extinct genus of large dicynodont synapsid with two recognized species: S. edentatus and S. parringtonii. Sangusaurus is named after the Sangu stream in eastern Zambia near to where it was first discovered + ‘saur’ which is the Greek root for lizard. Sangusaurus fossils have been recovered from the upper parts of the Ntawere Formation in Zambia and of the Lifua Member of the Manda Beds in Tanzania. The earliest study considered Sangusaurus a kannemeyeriid dicynodont, but more recent phylogenetic analyses place Sangusaurus within the stahleckeriid clade of Dicynodontia. Until recently, little work had been done to describe Sangusaurus, likely due to the fact that only four incomplete fossil specimens have been discovered.

Axitectum is an extinct genus of bystrowianid chroniosuchians from lower Triassic deposits of Nizhni Novgorod and Kirov Regions, Russia. It was a rather large animal judging by the size of its vertebrae. The back was covered in bands of highly ornamented osteoderm plates, similar to those found in modern crocodiles. The bands overlapped with the next band at the posterior end.

Dromotectum is an extinct genus of bystrowianid chroniosuchians from the Late Permian of China and Early Triassic of Russia. Two species have been named: the type species D. spinosum and the species D. largum. D. spinosum, the first species to be named, comes from Lower Triassic deposits in the Samara Region of European Russia and is known from the holotype PIN 2424/23, which consists of armor scutes, and from PIN 2424/65, 4495/14 and 2252/397. It was found in the Staritskaya Formation of the Rybinskin Horizon and named by I.V. Novikov and M.A. Shishkin in 2000. The generic name means “corridor with hipped vault” + “roof” (tecton), and the specific name means “spinous”. A second species, D. largum, was named by Liu Jun, Xu Li, Jia Song-Hai, Pu Han-Yong, and Liu Xiao-Ling in 2014 from the Shangshihezi Formation near Jiyuan in Henan province, China on the basis of specimen IVPP V 4013.1, a large scute.

Meyerosuchus is an extinct genus of mastodonsauroidean temnospondyl. Fossils have been found from the Early Triassic Hardegsen Formation in southern Germany. Meyerosuchus is present in late Olenekian deposits of the Middle Buntsandstein. The type species M. fuerstenberganus was named in 1966, although remains have been known since 1855. Meyerosuchus is closely related to Stenotosaurus; both genera are grouped in the family Stenotosauridae and the two genera may even be synonymous.

Phaanthosaurus is an extinct genus of basal procolophonid parareptile from early Triassic deposits of Nizhnii Novgorod, Russian Federation. It is known from the holotype PIN 1025/1, a mandible. It was collected from Vetluga River, Spasskoe village and referred to the Vokhmian terrestrial horizon of the Vokhma Formation. It was first named by P. K. Chudinov and B. P. Vjushkov in 1956 and the type species is Phaanthosaurus ignatjevi.

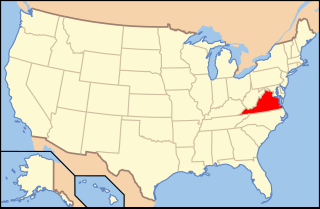

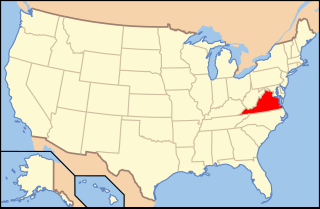

Paleontology in Virginia refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Virginia. The geologic column in Virginia spans from the Cambrian to the Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Virginia was covered by a warm shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and nautiloids. The state was briefly out of the sea during the Ordovician, but by the Silurian it was once again submerged. During this second period of inundation the state was home to brachiopods, trilobites and entire reef systems. During the mid-to-late Carboniferous the state gradually became a swampy environment.

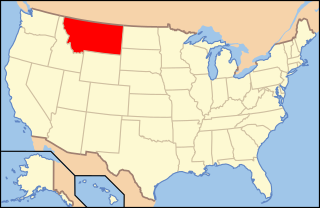

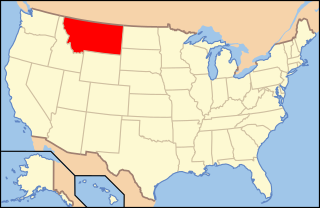

Paleontology in Montana refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Montana. The fossil record in Montana stretches all the way out to sea]] where local bacteria formed stromatolites and bottom-dwelling marine life left tracks on the sediment that would later fossilize. This sea remained in place during the early Paleozoic, although withdrew during the Silurian and Early Devonian, leaving a gap in the local rock record until its return. This sea was home to creatures including brachiopods, conodonts, crinoids, fish, and trilobites. During the Carboniferous the state was home to an unusual cartilaginous fish fauna. Later in the Paleozoic the sea began to withdraw, but with a brief return during the Permian.

Paleontology in Wyoming includes research into the prehistoric life of the U.S. state of Wyoming as well as investigations conducted by Wyomingite researchers and institutions into ancient life occurring elsewhere.

Paleontology in Oregon refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Oregon. Oregon's geologic record extends back approximately 400 million years ago to the Devonian period, before which time the state's landmass was likely submerged under water. Sediment records show that Oregon remained mostly submerged until the Paleocene period. The state's earliest fossil record includes plants, corals, and conodonts. Oregon was covered by seaways and volcanic islands during the Mesozoic era. Fossils from this period include marine plants, invertebrates, ichthyosaurs, pterosaurs, and traces such as invertebrate burrows. During the Cenozoic, Oregon's climate gradually cooled and eventually yielded the environments now found in the state. The era's fossils include marine and terrestrial plants, invertebrates, fish, amphibians, turtles, birds, mammals, and traces such as eggs and animal tracks.

Paleontology in Alaska refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alaska. During the Late Precambrian, Alaska was covered by a shallow sea that was home to stromatolite-forming bacteria. Alaska remained submerged into the Paleozoic era and the sea came to be home to creatures including ammonites, brachiopods, and reef-forming corals. An island chain formed in the eastern part of the state. Alaska remained covered in seawater during the Triassic and Jurassic. Local wildlife included ammonites, belemnites, bony fish and ichthyosaurs. Alaska was a more terrestrial environment during the Cretaceous, with a rich flora and dinosaur fauna.

The Park City Formation is a fossiliferous sedimentary formation from the late Permian of Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana. It is defined by its cherty, gray to pinkish limestone, calcareous siltstone, and cherty sandstone. The rocks in this formation formed along a shallow marine continental shelf and were regularly interrupted by the Phosphoria Formation due to tectonic forces and sea level change.

The Luning Formation is a geologic formation in Nevada. It preserves fossils dating back to the Triassic period.

The Kendlbach Formation is a Late Triassic to Early Jurassic (Hettangian) geological formation in Austria and Italy. It contains the Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the Hettangian stage at the Kuhjoch section in the Karwendel Mountains of Austria.

Diplopora is an extinct genus of marine dasycladacean algae in the family Diploporaceae.