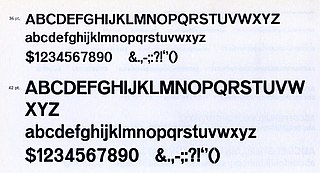

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called "serifs" at the end of strokes. Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than serif typefaces. They are often used to convey simplicity and modernity or minimalism. For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into these major groups: § Grotesque, § Neo-grotesque, § Geometric, § Humanist, and § Other or mixed.

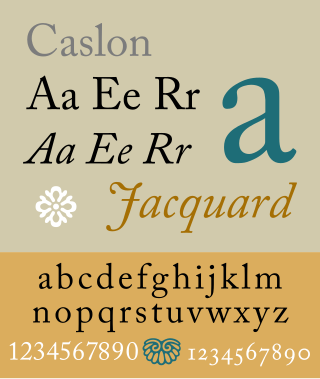

In typography, a serif is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a particular font or family of fonts. A typeface or "font family" making use of serifs is called a serif typeface, and a typeface that does not include them is sans-serif. Some typography sources refer to sans-serif typefaces as "grotesque" or "Gothic" and serif typefaces as "roman".

A typeface is a design of letters, numbers and other symbols, to be used in printing or for electronic display. Most typefaces include variations in size, weight, slope, width, and so on. Each of these variations of the typeface is a font.

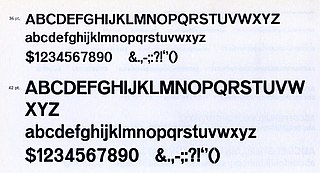

Univers is a large sans-serif typeface family designed by Adrian Frutiger and released by his employer Deberny & Peignot in 1957. Classified as a neo-grotesque sans-serif, one based on the model of nineteenth-century German typefaces such as Akzidenz-Grotesk, it was notable for its availability from the moment of its launch in a comprehensive range of weights and widths. The original marketing for Univers deliberately referenced the periodic table to emphasise its scope.

Gill Sans is a humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Eric Gill and released by the British branch of Monotype from 1928 onwards.

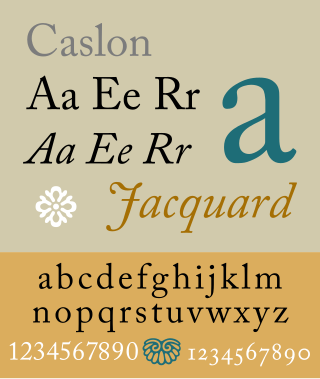

Caslon is the name given to serif typefaces designed by William Caslon I in London, or inspired by his work.

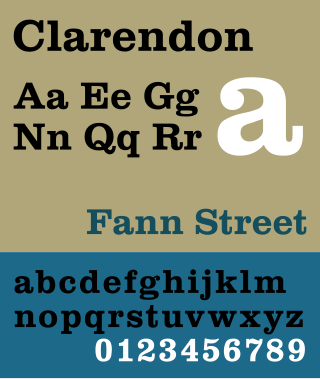

In typography, a slab serif typeface is a type of serif typeface characterized by thick, block-like serifs. Serif terminals may be either blunt and angular (Rockwell), or rounded (Courier). Slab serifs were introduced in the early nineteenth century.

Didone is a genre of serif typeface that emerged in the late 18th century and was the standard style of general-purpose printing during the 19th century. It is characterized by:

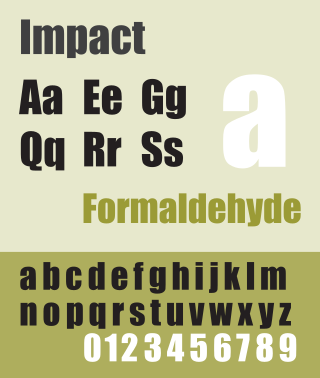

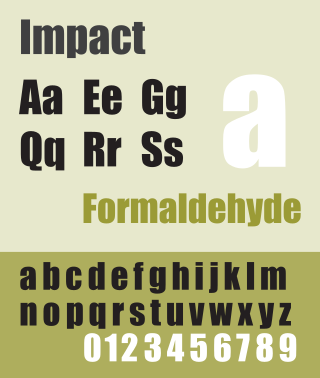

Impact is a sans-serif typeface in the industrial or grotesque style designed by Geoffrey Lee in 1965 and released by the Stephenson Blake foundry of Sheffield. It is well known for having been included in the core fonts for the Web package and distributed with Microsoft Windows since Windows 98. In the 2010s, it gained popularity for its use in image macros and other internet memes.

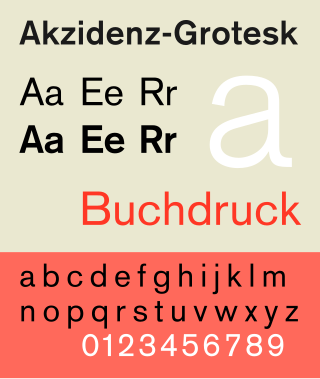

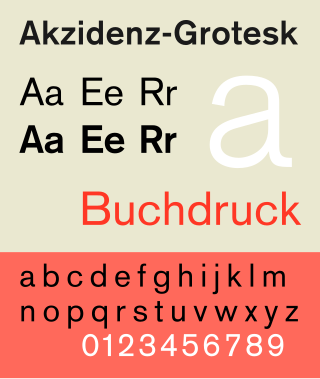

Akzidenz-Grotesk is a sans-serif typeface family originally released by the Berthold Type Foundry of Berlin. "Akzidenz" indicates its intended use as a typeface for commercial print runs such as publicity, tickets and forms, as opposed to fine printing, and "grotesque" was a standard name for sans-serif typefaces at the time.

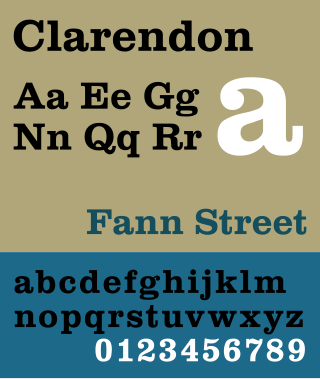

Clarendon is the name of a slab serif typeface that was released in 1845 by Thorowgood and Co. of London, a letter foundry often known as the Fann Street Foundry. The original Clarendon design is credited to Robert Besley, a partner in the foundry, and was originally engraved by punchcutter Benjamin Fox, who may also have contributed to its design. Many copies, adaptations and revivals have been released, becoming almost an entire genre of type design.

Monotype Grotesque is a family of sans-serif typefaces released by the Monotype Corporation for its hot metal typesetting system. It belongs to the grotesque or industrial genre of early sans-serif designs. Like many early sans-serifs, it forms a sprawling family designed at different times.

Jakob Erbar was a German professor of graphic design and a type designer. Erbar trained as a typesetter for the Dumont-Schauberg Printing Works before studying under Fritz Helmut Ehmcke and Anna Simons. Erbar went on to teach in 1908 at the Städtischen Berufsschule and from 1919 to his death at the Kölner Werkschule. His seminal Erbar series was one of the first geometric sans-serif typefaces, predating both Paul Renner's Futura and Rudolf Koch's Kabel by some five years.

Vincent Figgins was a British typefounder based in London, who cast and sold metal type for printing. After an apprenticeship with typefounder Joseph Jackson, he established his own type foundry in 1792. His company was extremely successful and, with its range of modern serif faces and display typefaces, had a strong influence on the styles of British printing in the nineteenth century. A successor company continued to make type until the 1970s.

Venus or Venus-Grotesk is a sans-serif typeface family released by the Bauer Type Foundry of Frankfurt am Main, Germany from 1907 onwards. Released in a large range of styles, including condensed and extended weights, it was very popular in the early-to-mid twentieth century. It was exported to other countries, notably the United States, where it was distributed by Bauer Alphabets Inc, the U.S. branch of the firm.

A reverse-contrast or reverse-stress letterform is a typeface or custom lettering where the stress is reversed from the norm, meaning that the horizontal lines are the thickest. This is the reverse of the vertical lines being the same width or thicker than horizontals, which is normal in Latin-alphabet writing and especially printing. The result is a dramatic effect, in which the letters seem to have been printed the wrong way round. The style was invented in the early nineteenth century as an attention-grabbing novelty for display typefaces. Modern font designer Peter Biľak, who has created a design in the genre, has described them as "a dirty trick to create freakish letterforms that stood out."

Egyptian is a typeface created by the Caslon foundry of Salisbury Square, London around or probably slightly before 1816, that is the first general-purpose sans-serif typeface in the Latin alphabet known to have been created.

Old Style, later referred to as modernised old style, was the name given to a series of serif typefaces cut from the mid-nineteenth century and sold by the type foundry Miller & Richard, of Edinburgh in Scotland. It was a standard typeface in Britain for literary and prestigious printing in the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, with many derivatives and copies released.

In typography, a fat face letterform is a serif typeface or piece of lettering in the Didone or modern style with an extremely bold design. Fat face typefaces appeared in London around 1805–1810 and became widely popular; John Lewis describes the fat face as "the first real display typeface."

In letterpress printing, wood type is movable type made out of wood. First used in China for printing body text, wood type became popular during the nineteenth century for making large display typefaces for printing posters, because it was lighter and cheaper than large sizes of metal type.