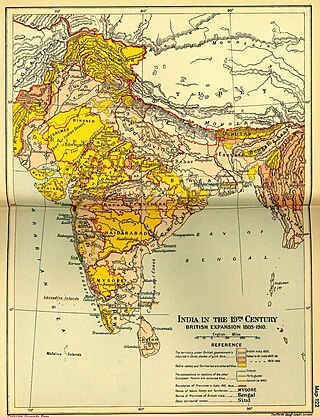

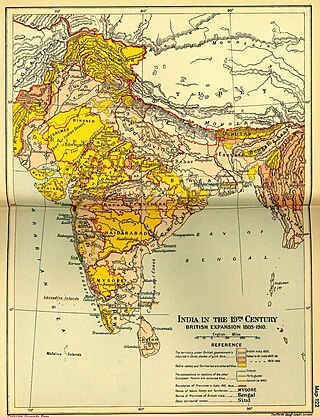

Company rule in India refers to regions of the Indian subcontinent under the control of the British East India Company (EIC). The EIC, founded in 1600, established their first trading post in India in 1612, and gradually expanded their presence in the region over the following decades. During the Seven Years' War, the East India Company began a process of rapid expansion in India which resulted in most of the subcontinent falling under their rule by 1857, when the Indian Rebellion of 1857 broke out. After the rebellion was suppressed, the Government of India Act 1858 resulted in the EIC's territories in India being administered by the Crown instead. The India Office managed the EIC's former territories, which became known as the British Raj.

Berar Province, also known as the Hyderabad Assigned Districts, was a province of Hyderabad. After 1853, it was administered by the British, although the Nizam retained formal sovereignty over the province. Azam Jah, the eldest son of the 7th Nizam, held the title of Mirza-Baig ("Prince") of Berar.

The Madras Presidency or Madras State, officially called the Presidency of Fort St. George until 1937, was an administrative subdivision (state) of British Raj and later the Republic of India. At its greatest extent, the presidency included most of southern India, including all of present-day Andhra Pradesh, almost all of Tamil Nadu and parts of Kerala, Karnataka, Odisha and Telangana in the modern day. The city of Madras was the winter capital of the presidency and Ooty (Udagamandalam) was the summer capital.

The Bombay Presidency or Bombay Province, also called Bombay and Sind (1843–1936), was an administrative subdivision (province) of India, with its capital in the city that came up over the seven islands of Bombay. The first mainland territory was acquired in the Konkan region with the Treaty of Bassein. Poona was the summer capital.

Dharwad, also known as Dharwar, is a city located in the northwestern part of the Indian state of Karnataka. It is the headquarters of the Dharwad district of Karnataka and forms a contiguous urban area with the city of Hubballi. It was merged with Hubballi in 1962 to form the twin cities of Hubballi-Dharwad. It covers an area of 213 km2 (82 sq mi) and is located 430 km (270 mi) northwest of Bangalore, on NH-48, between Bangalore and Pune.

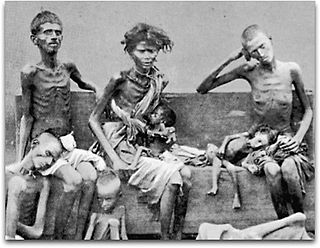

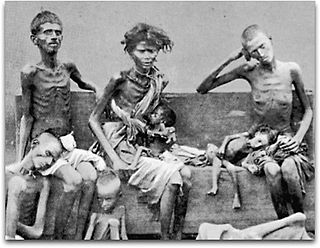

Famine had been a recurrent feature of life in the South Asian subcontinent countries of India and Bangladesh, most notoriously under British rule. Famines in India resulted in millions of deaths over the course of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. Famines in British India were severe enough to have a substantial impact on the long-term population growth of the country in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Deccan States Agency, also known as the Deccan States Agency and Kolhapur Residency, was a political agency of India, managing the relations of the Government of India with a collection of princely states and jagirs in western India.

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another, they existed between 1612 and 1947, conventionally divided into three historical periods:

The maund, mun or mann is the anglicized name for a traditional unit of mass used in British India, and also in Afghanistan, Persia, and Arabia: the same unit in the Mughal Empire was sometimes written as mann or mun in English, while the equivalent unit in the Ottoman Empire and Central Asia was called the batman. At different times, and in different South Asian localities, the mass of the maund has varied, from as low as 25 pounds (11 kg) to as high as 160 pounds (72 kg): even greater variation is seen in Persia and Arabia.

The Unification of Karnataka or Karnataka Ekikarana refers to the formation of the Indian state of Karnataka in 1956 when several Indian states were created by redrawing borders based on linguistic demographics. Decades earlier during British rule, the demand for a state based on Kannada demographics had been made.

Madhavrao II was the 12th Peshwa of the Maratha Confederacy, from his infancy. He was known as Sawai Madhav Rao or Madhav Rao Narayan. He was the posthumous son of Narayanrao Peshwa, murdered in 1773 on the orders of Raghunathrao. Madhavrao II was considered the legal heir, and was installed as Peshwa by the Treaty of Salbai in 1782 after First Anglo-Maratha War.

The Great Famine of 1876–1878 was a famine in India under British Crown rule. It began in 1876 after an intense drought resulted in crop failure in the Deccan Plateau. It affected south and Southwestern India—the British-administered presidencies of Madras and Bombay, and the princely states of Mysore and Hyderabad—for a period of two years. In 1877, famine came to affect regions northward, including parts of the Central Provinces and the North-Western Provinces, and a small area in Punjab. The famine ultimately affected an area of 670,000 square kilometres (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totalling 58,500,000. The excess mortality in the famine has been estimated in a range whose low end is 5.6 million human fatalities, high end 9.6 million fatalities, and a careful modern demographic estimate 8.2 million fatalities. The famine is also known as the Southern India famine of 1876–1878 and the Madras famine of 1877.

The Indian famine of 1896–1897 was a famine that began in Bundelkhand, India, early in 1896 and spread to many parts of the country, including the United Provinces, the Central Provinces and Berar, Bihar, parts of the Bombay and Madras presidencies, and parts of the Punjab; in addition, the princely states of Rajputana, Central India Agency, and Hyderabad were affected. All in all, during the two years, the famine affected an area of 307,000 square miles (800,000 km2) and a population of 69.5 million. Although relief was offered throughout the famine-stricken regions in accordance with the Provisional Famine Code of 1883, the mortality, both from starvation and accompanying epidemics, was very high: approximately one million people are thought to have died.

The Indian famine of 1899–1900 began with the failure of the summer monsoons in 1899 over Western and Central India and, during the next year, affected an area of 476,000 square miles (1,230,000 km2) and a population of 59.5 million. The famine was acute in the Central Provinces and Berar, the Bombay Presidency, the minor province of Ajmer-Merwara, and the Hissar District of the Punjab; it also caused great distress in the princely states of the Rajputana Agency, the Central India Agency, Hyderabad and the Kathiawar Agency. In addition, small areas of the Bengal Presidency, the Madras Presidency and the North-Western Provinces were acutely afflicted by the famine.

David Price was a Welsh orientalist and officer in the East India Company.

Madras Presidency was an administrative subdivision (presidency) of British India. At its greatest extent, Madras Presidency included much of southern India, including the present-day Indian State of Tamil Nadu, the Malabar region of North Kerala, Lakshadweep Islands, the Coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema regions of Andhra Pradesh, Undivided Koraput and Ganjam districts of Orissa and the Bellary, Dakshina Kannada, and Udupi districts of Karnataka. The presidency had its capital at Madras.

Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency is a publication of the erstwhile British India first published in the year 1884 and printed at the Government Central Press, Bombay in 1884. Since the early 19th Century the English East India Company and later the British Empire annexed most of Western India and collectively named the provinces in Western India as Bombay Presidency.

The elections to the two houses of legislatures of the Bombay Presidency were held in 1937, as part of the nationwide provincial elections in British India. The Indian National Congress was the single largest party by winning 86 of 175 seats in the Legislative Assembly and 13 of 60 seats in the Legislative Council.

Belagavi railway station, formerly Belgaum railway station is a railway station under South Western Railways and it is the primary railway station serving Belagavi in North Western Karnataka. It is a "A" Category station.