World War II

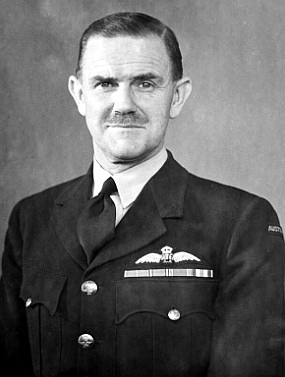

Wilson's ... tenacious pursuit [at the Air Court of Inquiry into the 1940 Canberra air disaster] of a theory that could not be proved appears consistent with Jack Graham's memory of him as 'a most peculiar bloke, [a] most erratic fellow...he was quite unpredictable'. Joe Hewitt, who knew Wilson well, described him as an introvert. 'He was,' Hewitt remembered, 'a violinist of some ability, and would often lose himself in playing a wealth of classical music.' But, as the Air Court demonstrated, he would not remain in his shell when circumstances permitted his forceful presence.[According to the wartime head of public relations for the RAAF] John Harrison ... when Wilson became a POW and senior British officer in Stalag Luft III, someone who had either 'served or suffered' under him remarked: 'God help the Germans.'

The Pacific

Wilson commanded RAAF stations and held staff positions in Australia for the first few years of the war. [3]

After the crash at Canberra in 1940 of an RAAF Lockheed Hudson, which killed 10 people, including three members of Cabinet and the army's Chief of General Staff (General Sir Brudenell White), Wilson was appointed technical assistant to Arthur Dean, counsel assisting the Air Court of Inquiry that followed. [1]

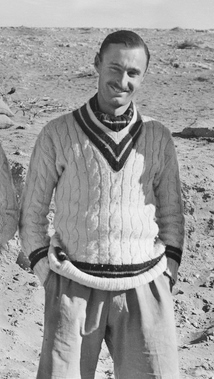

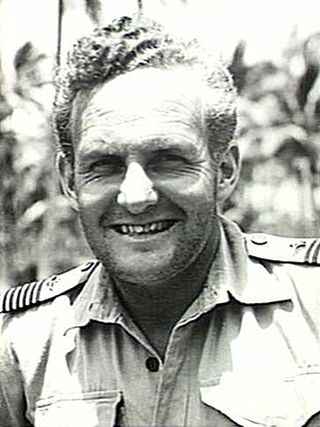

In late 1941, Wilson – with the rank of acting Air Commodore – was appointed commander of North-West Area (NWA), a newly formed RAAF command, headquartered at RAAF Darwin. [3] On 20 January 1942, the Australian government temporarily ceded operational control of military forces in northern Australia to ABDACOM : [6] an ambitious, but short-lived and shambolic supreme command, encompassing Allied forces throughout South East Asia and the South West Pacific. As a result, Wilson nominally headed an ABDACOM subcommand, AUSGROUP (sometimes "Darwin Command"): in addition to NWA, AUSGROUP nominally controlled Allied military aviation in Dutch New Guinea, the Molucca Sea and the northern part of RAAF Western Area. [7] Wilson's immediate superior was the commander of Allied air forces (ABDAIR), Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse (RAF), who reported directly to General Sir Archibald Wavell (British Army), supreme commander of ABDACOM whose headquarters were at Bandung (Bandoeng), in Java.

Observing that any concentration of military aviation facilities, aircraft and personnel, at a relatively small airfield, made it vulnerable and attractive to enemy attack, Wilson began to consider dispersal and decentralisation. Following reports, on 27 January, that the formidable Japanese combined carrier fleet had entered the Flores Sea, Wilson ordered the dispersal of assets at RAAF Darwin. Repair and maintenance equipment and staff were moved to Daly Waters, almost 300 miles (480 km) further south. [8] However, when Wilson also ordered the transfer of obsolete aircraft (five CAC Wirraway armed trainers belonging to No. 12 Squadron RAAF) to Daly Waters, he was overruled by the Deputy Chief of Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal William Bostock. (Three of the Wirraways were damaged and written-off following the first air raid on Darwin – see below.) [8] At around the same time, Wilson ordered the arrest of a civilian suspected of signalling enemy vessels using an improvised signal lamp, from a location near RAAF Darwin. [9] During early February, NWA was inspected by Air Commodore George Jones (soon to be appointed Chief of the Air Staff), who reported deficiencies in morale and aircraft serviceability amongst its combat units: 2, 12 and 13 squadrons. [10]

On 19 February, while Wilson was attending to ABDACOM duties in Java, Darwin suffered a massive air raid. The Allies suffered significant losses: at least 236 civilians and military personnel were killed, 11 vessels were sunk in Darwin Harbour and 31 aircraft were destroyed. [11] [12] The only fighter aircraft present, a squadron of P-40E Warhawks of the United States Army Air Force, were overwhelmed and/or destroyed on the ground. By the end of March Allied resistance in the Dutch East Indies had collapsed by the end of March, and ABDA was dissolved, along with its sub-commands. Criticised regarding their preparations for and responses to the first air raids, Wilson, his deputy, Group Captain Frederick Scherger, and the station commander of RAAF Darwin, Wing Commander Sturt Griffith, were posted out of NWA.

Europe

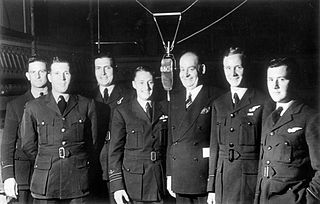

Wilson was attached on exchange to the RAF in January 1943 and posted as a Group Captain to the UK, where he served as Officer Commanding at three RAF Bomber Command stations in rapid succession: RAF Wyton, RAF Linton-on-Ouse, and RAF Holme-on-Spalding Moor. [3]

During this period, Bomber Command was involved in a pivotal strategic bombing campaign against the Ruhr, where German war industries were concentrated. These targets were heavily defended and Allied losses were considerable. The casualty rate, combined apparently with the blunt tone of Wilson's instructions to aircrews under his command, attracted the antipathy of some of them. For example, one pilot, Flight Lieutenant Ron Read (RAF), commented that

- Wilson was a dry humourless Australian, who had ... had no [direct] experience ... in operations. What made him very unpopular was his attitude in his first couple of briefings, telling us, most ... veterans of many ops, how we should press on ... to attack the heavy Ruhr targets, which we were doing two or three times a week in some cases. [13]

According to Read, senior aircrew suggested to Wilson that perhaps he should fly on an operation himself, believing that afterwards he might not be "so critical" or, "we slyly thought ... might go for the chop himself" (i.e. be shot down).

Wilson flew operationally, for the first and only time, on the night of 22/23 June 1943. [3] He was officially, second pilot of a Handley Page Halifax Mk V, DK224 (squadron code "MP-Q"), from 76 Sqn RAF, captained by Pilot Officer James Carrie (RAF). DK224 was the last bomber to reach and bomb a target at Mülheim, Germany that night. [14] On the return leg, at about 0158 hours, the bomber came under attack over the Netherlands, by Luftwaffe night-fighter ace, Oberleutnant Werner Baake of 1./NJG1 . [15] After the Halifax was severely damaged by Baake and the controls became unresponsive, Carrie ordered the crew to bale out. The flight engineer, Sgt Richard Huke (RAF), was killed by a parachute malfunction; the other members landed safely, close to Zuylen Castle.

While several crew members were captured soon afterwards, Wilson, Carrie and wireless operator Sgt Elliott McVitie (RAF) made contact with a Dutch resistance "escape line" known as Luctor et Emergo (later Fiat Libertas), which had been organised to smuggle Allied aircrews out of occupied Europe. [16] [17] They travelled undercover into Belgium, where they were handed over to the better-known "Comet line". However, during the first week of August, Wilson, Carrie and McVitie were apprehended in Paris, by either the Gestapo or GFP , and became prisoners of war (POW). [3]

At Stalag Luft III (SLIII), near Sagan, Silesia (now Żagań, Poland), Wilson reportedly assisted in a successful escape, which one of the escapees, Flight Lieutenant Eric Williams (RAF), later recounted in a book that became a popular film adaptation: The Wooden Horse (1950). [3]

The even more famous "Great Escape" of March 1944, which took place in another compound at SLIII, did not involve Wilson. However, he succeeded Gp Capt. Herbert Massey as the Senior British Officer (SBO) at SLIII soon afterwards. On 17 April 1944, Wilson surreptitiously passed to an official visitor from the Swiss Red Cross a list, compiled by other POWs, giving the names of 47 Allied personnel whom POWs believed had been murdered following the Great Escape by the Gestapo. [18] It was later established that 50 Allied POWs were shot on the personal orders of Adolf Hitler. (Wilson would later gave statements to war crimes prosecutors regarding these and other events.)

After the camp was liberated, two former POWs who had been convicted of collaborating with German authorities made similar accusations against Wilson. He was not charged after the British Judge Advocate General found that no offence had been committed. [19]