Falstaff is a comic opera in three acts by the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi. The Italian-language libretto was adapted by Arrigo Boito from the play The Merry Wives of Windsor and scenes from Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2, by William Shakespeare. The work premiered on 9 February 1893 at La Scala, Milan.

Cecil Antonio Richardson was an English theatre and film director, producer and screenwriter, whose career spanned five decades. He was identified with the "angry young men" group of British directors and playwrights during the 1950's, and was later a key figure in the British New Wave filmmaking movement.

Peter Seamus O'Toole was an English stage and film actor. He attended RADA and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic and with the English Stage Company. In 1959 he made his West End debut in The Long and the Short and the Tall, and played the title role in Hamlet in the National Theatre's first production in 1963. Excelling on the London stage, O'Toole was known for his "hellraiser" lifestyle off it.

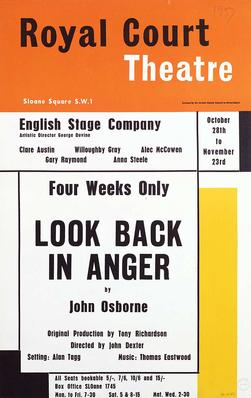

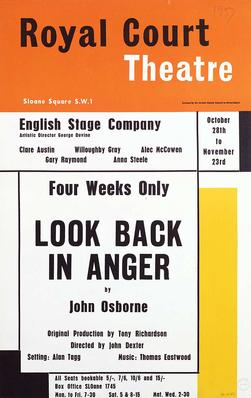

The "angry young men" were a group of mostly working- and middle-class British playwrights and novelists who became prominent in the 1950s. The group's leading figures included John Osborne and Kingsley Amis; other popular figures included John Braine, Alan Sillitoe, and John Wain. The phrase was originally coined by the Royal Court Theatre's press officer in order to promote Osborne's 1956 play Look Back in Anger. It is thought to be derived from the autobiography of Leslie Paul, founder of the Woodcraft Folk, whose Angry Young Man was published in 1951.

John James Osborne was an English playwright, screenwriter, actor, and entrepreneur. Born in London, he briefly worked as a journalist before starting out in theatre as a stage manager and actor. He lived in poverty for several years before his third produced play, Look Back in Anger (1956), brought him national fame.

Look Back in Anger (1956) is a realist play written by John Osborne. It focuses on the life and marital struggles of an intelligent and educated but disaffected young man of working-class origin, Jimmy Porter, and his equally competent yet impassive upper-middle-class wife Alison. The supporting characters include Cliff Lewis, an amiable Welsh lodger who attempts to keep the peace; and Helena Charles, Alison's snobbish friend.

Kitchen sink realism is a British cultural movement that developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s in theatre, art, novels, film and television plays, whose protagonists usually could be described as "angry young men" who were disillusioned with modern society. It used a style of social realism which depicted the domestic situations of working-class Britons, living in cramped rented accommodation and spending their off-hours drinking in grimy pubs, to explore controversial social and political issues ranging from abortion to homelessness. The harsh, realistic style contrasted sharply with the escapism of the previous generation's so-called "well-made plays".

The Royal Court Theatre, at different times known as the Court Theatre, the New Chelsea Theatre, and the Belgravia Theatre, is a non-commercial West End theatre in Sloane Square, London, England. In 1956 it was acquired by and remains the home of the English Stage Company, which is known for its contributions to contemporary theatre and won the Europe Prize Theatrical Realities in 1999.

Eileen Mary Ure was a British actress. She was the second Scottish-born actress to be nominated for an Academy Award, for her role in the 1960 film Sons and Lovers.

Alison Brown is an American banjo player, guitarist, composer, and producer. She has won and has been nominated for several Grammy awards and is often compared to another banjo prodigy, Béla Fleck, for her unique style of playing. In her music, she blends bluegrass, jazz, Latin and Celtic influences.

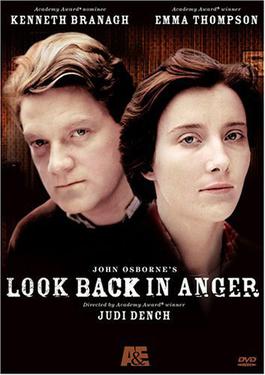

The Renaissance Theatre Company was a theatre company founded in 1987 by Kenneth Branagh and David Parfitt. It was disbanded in 1992.

Anthony Creighton, a British actor and writer, is best known as the co-author of the play Epitaph for George Dillon with John Osborne.

Kenneth William Michael Haigh was an English actor. He first came to public recognition for playing the role of Jimmy Porter in the play Look Back in Anger in 1956 opposite Mary Ure in London's West End theatre. Haigh's performance in the role on stage was critically acclaimed as a prototype dramatic working-class anti-hero in post-Second World War English drama.

Look Back in Anger is a 1959 British kitchen sink drama film starring Richard Burton, Claire Bloom and Mary Ure and directed by Tony Richardson. The film is based on John Osborne's play about a love triangle involving an intelligent but disaffected working-class young man, his upper-middle-class, impassive wife (Alison) and her haughty best friend. Cliff, an amiable Welsh lodger, attempts to keep the peace. The character of Ma Tanner, only referred to in the play, is brought to life in the film by Edith Evans as a dramatic device to emphasise the class difference between Jimmy and Alison. The film and play are classic examples of the British cultural movement known as kitchen sink realism.

A Better Class of Person (1981) is an autobiography written by dramatist John Osborne and published in 1981. Based on Osborne's childhood and early life, it ends with the first performance of Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court Theatre in 1956. The book emphasises his warm relationship with his father Thomas, and his antagonistic relationship with his mother Nellie Beatrice, which deepened to hatred after his father died when John was young. A sequel, Almost a Gentleman, was published in 1991.

Look Back in Anger is a 1980 British film starring Malcolm McDowell, Lisa Banes and Fran Brill, and directed by Lindsay Anderson and David Hugh Jones. The film is based on John Osborne's play Look Back in Anger.

Epitaph for George Dillon is an early John Osborne play, one of two he wrote in collaboration with Anthony Creighton. It was written before Look Back in Anger, the play which made Osborne's career, but opened a year after at Oxford Experimental Theatre in 1957, and was then produced at London's Royal Court theatre, where Look Back in Anger had debuted. It transferred to New York City shortly afterwards and garnered three Tony Award nominations.

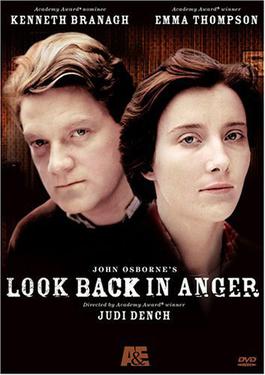

Look Back in Anger is a 1989 British videotaped television production of John Osborne's play. It features Kenneth Branagh, Emma Thompson, Siobhan Redmond, Gerard Horan, and Edward Jewesbury. It was directed by Judi Dench; and produced by Humphrey Barclay, Moira Williams, and First Choice Productions for Thames Television.

The World of Paul Slickey (1959) is a play by John Osborne. It was Osborne's only musical, intended as a social satire on high-society gossip columnists. After the huge successes of Osborne's previous plays Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer, the play was to become "one of the most spectacular disasters in English theatre".

Christopher Whelen was an English composer, conductor and playwright, best known for his radio and television operas. Because much of his work was written for specific theatre productions in the 1950s, or directly for broadcast in the 1960s to the 1980s, little of it survives today, though a number of his scores and related papers have been deposited in the British Library.